Five Years Later, Not Much Doom (Yet!)...

Remember five years ago, when Olivier Blanchard was saying that Japan would face a solvency crisis and be forced to inflate away its debt within the next five years? Good times. https://t.co/2tbAbyVu0H

— JW Mason (@JWMason1) June 25, 2021

J.W. Mason put out this snarky tweet that had a follow-up that linked to one of my articles (that I have long forgotten about!): Olivier Blanchard Joins The “Japan Is Doomed!” Crowd. To be slightly fair to Blanchard, what I referred to was an interview with a journalist and not long-form content of his own.

NOTE: The Feedburner email service is being discontinued. If you wish to receive my articles via email, you need to sign up for my free Substack: https://bondeconomics.substack.com/

He was quoted as saying (which based on my experience, does not guarantee that is exactly what he said!):

One day the BoJ may well get a call from the finance ministry saying please think about us – it is a life or death question - and keep rates at zero for a bit longer. [...]

The risk of fiscal dominance, leading eventually to high inflation, is definitely present. I would not be surprised if this were to happen sometime in the next five to ten years.

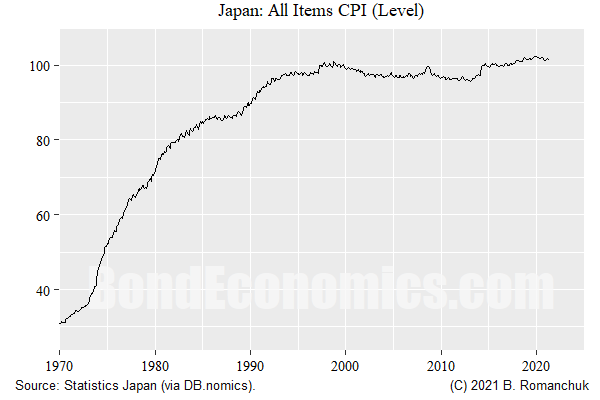

As J.W. Mason noted, the first five years of his forecast horizon is up. Below, I update a chart I showed in the 2016 article (although the chart below is headline CPI, I used earlier a variant that had a longer history).

Although I am not pretending to be a forecaster, I would argue that my comments stood up relatively well.

If we take the notion of “revealed preference” seriously, we have to conclude that Japanese policymakers want to achieve a target of price level stability. As the chart above shows, if that is the case, they have achieved their objective. The price level (as measured by a non-standard CPI index, but which has a longer history than the headline CPI) has been in a band 5% since the early 1990s.

As part of my inflation primer, I hope to dig further into Japan’s post-1990 “inflation” experience, but it does appear to be an interesting example of a fiat currency achieving price level stability. This stabilization is ignored for two reasons:

- western mainstream economists are convinced that 2% inflation is the “correct” level for inflation targeting, and they browbeat Japan for “deflation,” and

- everybody is predicting the imminent collapse of the Japanese yen into hyperinflation due to “unsustainable” fiscal deficits and “money printing.”

I do not make forecasts, so I normally try to avoid poking fun at forecasts that go wrong. (In fact, in the cases of recessions, my shtick is that they are inherently hard to forecast, not counting oddities like the 2020 recession). However, I will go after crackpot “fiscal collapse” and “out of control inflation” theories, particularly in the case of Japan. “Experts” have been consistently and totally wrong about the effects of Japanese fiscal policy (and “money printing!”) since the mid-1990s, and market participants were well aware of the “Widowmaker Trade” when I started in finance in 1998. There was no excuse to make the same ridiculous mistake in 2016.

Although I am thankful for J.W. Mason digging up this gem (and helping fill my content void!), this anecdote ties into what I have been thinking about as I am trying to re-orient myself with respect to current economic debates. I have not followed the economic data too closely since the pandemic hit, on the basis that it was too novel a situation for me, and the best use of my time was to focus on my books. Now that we are returning to something closer to normalcy, it will be easier for me to offer comments on the data flow with at least some form of confidence, even though I am not working full time as an economy watcher.

My concern is that I am very underwhelmed by the value of a lot of economic theories, particularly mainstream theory. To what extent mainstream economics has value, it is probably in the area of empirical work. (Post-Keynesians have complaints about that as well, but digging into that is not a priority for me.) Mainstream economic theory largely rides on the coattails of that empirical work, as well as the general deference to credentialism.

-

Blanchard’s discussion of “fiscal dominance” is an example of jargon overpowering anything resembling common sense. What is fiscal dominance, anyway? Why is it bad? What value did the stochastic calculus give Blanchard in making his assessment of risks in Japan in 2016?

-

What insights did neoclassical theory give us about the pandemic (and post-pandemic economy)? The importance of “inflation expectations”? If a significant portion of the population believes that inflation is “really 10%”, in what sense are “inflation expectations anchored”?

Although I enjoy dumping on mainstream economic theory as much as the next person, I will finish off by noting that I do not think that mainstream economics did as badly on a relative basis as was the case in the Financial Crisis. In the Financial Crisis (and its aftermath), the added value of neoclassical economics was negative — which helped push me in the direction of heterodox economics when I was still working in finance. In the pandemic, it was more of a question to reacting to the events, which economists of a wide variety of backgrounds were able to do with differing success. (The only obvious analytical failures were the usual suspects calling for hyperinflation).

With economic dynamics returning closer to normal, my gut reaction would be that the heterodox/neoclassical fault lines would revolve around the “mystery variables” (like NAIRU, r*, etc.) which are a core part of the neoclassical toolkit. However, the data deviations have obliterated the techniques used to estimate those variables, so we end up with a much more fluid theoretical situation where it is much harder to make generalizations.

Disclaimer: This article contains general discussions of economic and financial market trends for a general audience. These are not investment recommendations tailored to the particular needs of an ...

more