Expect The Unexpected: 10 Reasons North Korea Could Soon Change Course

1. Russia’s economy is currently in disarray as a result of falling commodity prices, slow economic growth in Europe, and its rivalry with the United States. Russia has been an ally of North Korea because it sees North Korea as a counterweight to the Chinese, Japanese, and US-backed South Koreans, the other powers in Northeast Asia. If Russia’s economy does not bounce back, North Korea will need to adapt to the weakening of one of its only friends in the world.

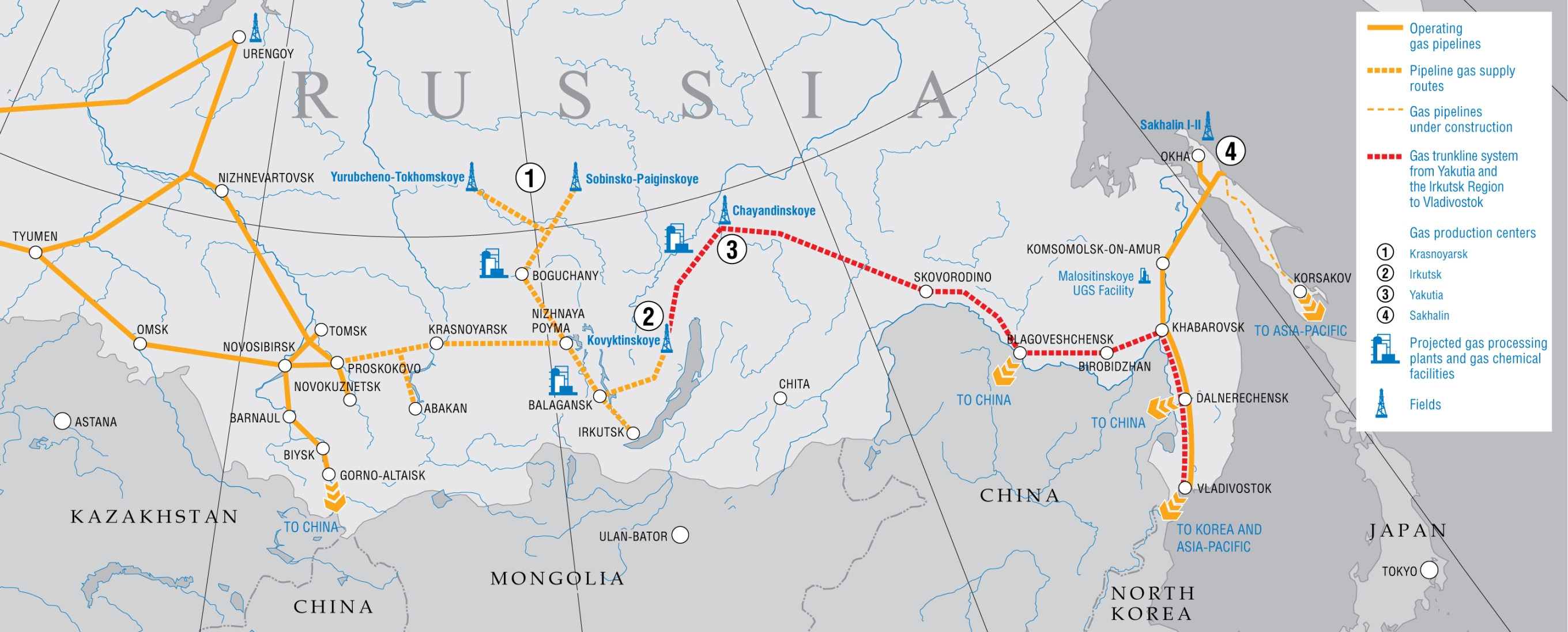

2. Russia has been looking to export commodities to South Korea, as Russia worries that the Ukraine conflict, the American fracking boom, the end of Western sanctions on Iran, and the possibility of Japan turning its nuclear power plants back on will lead Europe and Japan to reduce their imports of Russian oil and gas. Though Russia is obviously not thrilled about South Korea’s close relationship with the United States, it might nevertheless be happy to see a more united Korea serve as a counterweight to China and Japan in the Pacific.

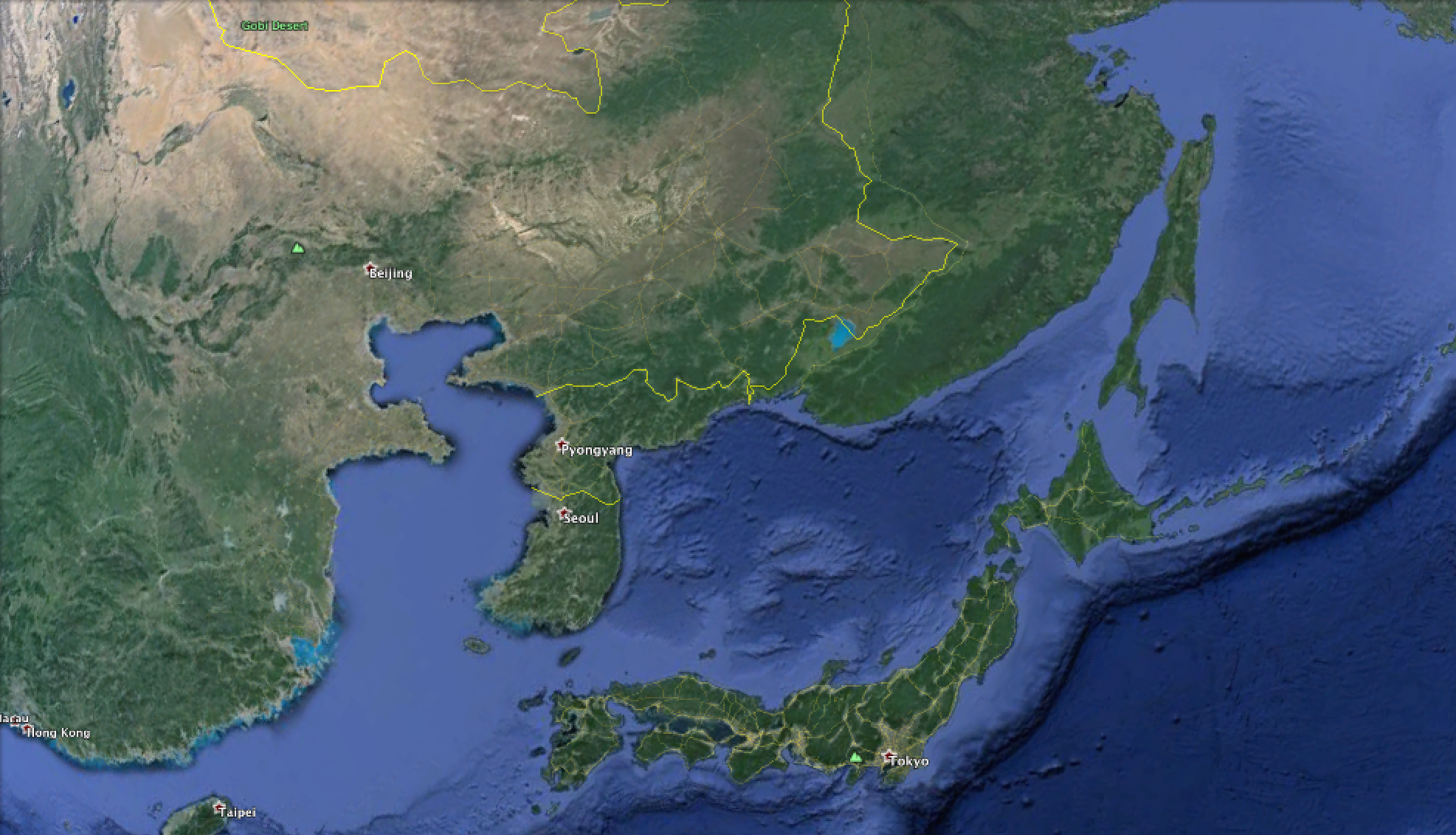

In addition, the most direct way for Russia and South Korea to trade with one another is via the 800 km of North Korean territory that separates Seoul from Vladivostok. This is particularly true of gas exports, which travel cheapest through overland pipelines rather than by undersea pipelines or LNG ships. It is also true of many other types of goods, however. Politics aside, it would often make more sense to cross North Korea rather than to load and unload ships in order to sail the 600 km of sea between Russia and eastern South Korean ports (which are themselves 150 km or so from Seoul).

3. The youngest generation of the North Korean leadership, embodied by 33-year old Kim Jong Un, was raised during the 1990s, after the Soviet Union had fallen, China’s economic miracle had begun, and the Internet and satellite television had become common. Kim Jong Un himself went to school in Switzerland, a stark contrast to his father Kim Jong Il who may have been educated in China during the Maoist era.

Today Kim must be looking at Bashar al-Assad with fear. Like Kim, Assad took over at a fairly young age from a father who had been a larger than life figure. Assad lasted for one decade before the Syrian Civil War got underway; Lil’ Kim is now in the middle of his fifth year in office. Meanwhile, the number of North Koreans living today who were alive during the reign of the first Kim, Il Sung, is quickly falling.

4. Unlike most other poor countries, North Korea’s population is not young. Its population pyramid has two main bulges: one between 40-50 years old, the other between 15-25 years old. A decade from now, then, much of the older bulge will have become too old for manual labor, while the number of young people entering the workforce for the first time will have begun to drop off. At this point, North Korea may be more inclined to move away from a labor-based economy, which in turn will require it to import capital from abroad, perhaps from the South Koreans.

This aging also raises Korea’s family reunification issue: North Korea’s 40-50 year old cohort are in many cases the children of families who were divided by the peninsula’s split in the Korean War. The coming decade will be the last chance for many of these sundered families to get back in touch before their elderly parents pass away — and before this generation becomes old itself.

5. Back when China was run by committee, consensus, compromise, etc., it liked being compared to North Korea because it could say, in effect, “we may not have a liberal democratic political system, but at least we’re nothing like the government in North Korea”. Today, though, as China has been moving back in the direction of a more traditional persona-led dicatorship embodied by Xi Jinping, the last thing that the Chinese leadership wants is for Xi to be compared with Kim Jong Un.

Xi has yet to visit North Korea, even though Xi has been perhaps the most well-travelled leader in Chinese history, and the first ever to visit South Korea before North Korea. Kim Jong Un, in turn, has not yet travelled the 800 km from Pyongyang to Beijing. (In fact, Kim Jong Un has never officially left North Korea since taking over as its leader in 2012). This may soon change, however: Kim Jong Un may finally visit Beijing in the next few months.

6. Japan could be coming back in a big way: Shinzo Abe’s revivalism - including the end of formal military pacifism and the symbolic 2020 Tokyo Olympics - may just be the start. The Japanese economy is far less exposed to the Chinese economic slowdown as are those of South Korea and Taiwan. Japan might benefit more from Russia’s troubles than China will, given that China has often allied itself with Russia. Japan is also more dependent on energy imports than China, and so may be more likely to benefit from the fall in energy prices than China will.

Japan may benefit more than any other country from the coming era of robots, given its uniquely aging workforce and technological expertise — and given that robots might make China’s enormous human workforce less valuable. Whether Japan addresses its aging workforce dilemma by importing more energy to power robots or by continuing to outsource more of its industrial activity to countries like Thailand and Taiwan, it will have to become more active in the region, and thus potentially more aggressive in the region, in order to ensure its access to foreign markets.

If Japan’s reemergence causes the Chinese to want to create a rift in the US-Japan alliance, Korea is the best place for China to try to do so. The US loves its alliance with Korea, while Japan does not. The Japanese and Koreans have quite a tortured relationship, a legacy of Japan’s historical domination of the peninsula. The US would be thrilled by a more unified Korea, whereas the Japanese might be wary of one even in spite of their current rivalry with the North.

Consider the context for the Korean War (1950-1953): Japanese power had just been decimated in World War Two, so China helped to divide the Korean peninsula because it feared the American-allied unified Korea that had emerged at Beijing’s doorstep. China did not have to consider using Korea to create a rift between the US and Japan, since Japan was not a player at the time. A somewhat similar situation occurred in 1990, when American power surged again as the Soviet Union fell and as Japan’s economy suddenly began its “lost decades” of slowing growth.

If Japanese power grows, however, China may want a more unified Korea as a buffer against the Japanese and as a prime way of splitting the American-Japanese alliance. Alternatively, if China and Japan can finally mend fences with one another politically, it may cause the United States (and/or Russia) to want a more unified Korea to serve as a buffer against both China and Japan.

7. More so than during the 1990s, when Russia and China were weaker than they are now and 9-11 had not yet occurred, the US has a lot to worry about today other than North Korea’s military programs. North Korea’s first nuclear tests were in 2005, possibly in order to win back American attention that had shifted to the Greater Middle East. Now, though, with the US still worried about the Muslim world and also concerned with Russia and China, there may be diminishing returns to this strategy of gaining aid and prestige by nuclear saber-rattling.

The move by North Korea in 2010 to kill 46 South Korean navy soldiers in the Cheonan ship attack, which was by far the most casualties the South’s military has experienced in decades, suggests that the North Korean leadership may be aware of these diminishing returns. More recently, so does the announcement by North Korea this past winter that it has successfully developed a hydrogen bomb.

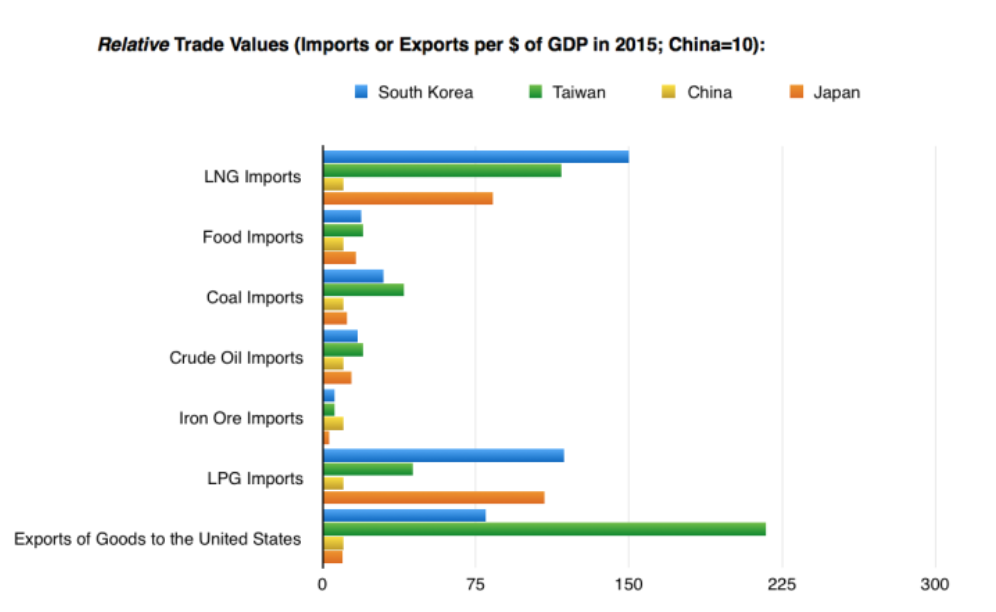

8. South Korea’s economy is slowing because of China’s economic slowdown and because South Korea has now basically become a “developed” economy (its per capita income is estimated to be $28,000, in nominal terms). While South Korea does not want to pay the financial burden of resuscitating the North Korean economy, it could nevertheless see some opportunities for itself in engaging the North in trade.

North Korea, for example, has one of the world’s largest reserves of high-quality anthracite coal, while South Korea is one of the world’s leading importers of coal and of fossil fuels in general. And of course, North Korea has a cheap, Korean labor pool (and potential consumer base), at a time when South Korea’s workforce is no longer cheap or youthful by global standards.

Trade figures, adjusted for overall GDP size

9. Coal prices have plunged of late in China and in most of the rest of the world. This could put a lot of pressure on the North Korean economy, which has become the third largest supplier of coal to China in recent years. China accounts for more than 90 percent of all North Korean international trade. According to Reuters, “last year, North Korean coal deliveries to China surged 26.9, making North Korea China’s biggest supplier behind Australia and Indonesia. Coal deliveries from Australia plunged 25 percent, indicating the increase in [Korean] imports may have been to help support this”.

10. With China and the wider Northeast Asian economy struggling after years of rapid expansion, ending North Korea’s isolation could be a good last-ditch attempt to stimulate regional growth. China, for instance, could try to use its position as the North Korea whisperer in order to gain economic favors from the United States. China also has an incentive to engage North Korea — and to South Korea engage North Korea — because the last thing it wants to deal with right now is a refugee crisis emerging on its border with North Korea in the unlikely (but not impossible) event of a state collapse occuring there. Millions of Koreans already live in China near the North Korean border.

Finally, North Korea could benefit the regional economy by serving as a land route between China and South Korea. Seoul is just 500-600 km from significant Chinese cities like Shenyang and Dalian and 1150 km from Bejing by way of the North. In the longer-term, the North Korean trade route could become even more commercially important if fixed links are built across the Yellow Sea between North Korea and China, across the Gulf of Bohai between the Chinese provinces of Liaoning and Shandong, or across the Korea Strait from Japan to the Korean peninsula.

So, could the era of extreme North Korean isolation from the world be reaching its final days? Certainly, from the US point of view, North Korea is the last man standing. Of the six countries that the Bush government named as the “axis of evil” - Iraq, Iran, Syria, Libya, Cuba, and North Korea - Kim is now the only leader not to have either been toppled (Iraq and Libya), besieged (Syria), or moved towards warmer relations with the US (Cuba and Iran). Given the changes occurring all around it in Asia and the world, North Korea's position no longer seems like an easily sustainable one. Reunification with the South or not, it still makes sense to guess that North Korea under Kim Jong Un will end up being very different from that of his father.

Disclosure: None.