“Foreign Direct Investment Under Uncertainty” Up To 2019

A new paper in the Review of International Economics coauthored with Caroline Jardet and Cristina Jude (both Banque de France). From the conclusion:

FDI flows have been particularly weak in the years preceding the pandemic, while traditional drivers like growth or historically low interest rates should have been supportive of a stronger dynamic. This suggests that structural factors beyond those usually found to drive FDI inflows, such as the increased economic uncertainty in the aftermath of the GFC, may have deterred FDI inflows. While there is an enormous extant literature analyzing the empirical determinants FDI, the empirical analysis of uncertainty’s impact is relatively small, partly explained by the lack of consistent cross-country measures of policy uncertainty.

In this paper, we examine the role of uncertainty in driving FDI inflows in a heterogeneous sample of advanced, emerging market and developing countries over a 25-year long pre-Covid period from 1995 to 2019. By relying on a push-pull framework, we control for both host country as well as global uncertainty. Stratifying the sample according the development levels allows us to discern effects of different strength and directions among the country groups.

We thus find that it is not host country uncertainty that seems to matter the most for FDI inflows, but rather global uncertainty. Domestic economic and political uncertainty is usually statistically insignificant for FDI inflows. These results hold despite variations in the global and host country measures of uncertainty.

For emerging countries, and in certain conditions only, host countries uncertainty seems to also have a negative effect on FDI flows, but to a lesser extent compared to global uncertainty. Domestic uncertainty does not seem to be an important driver of FDI inflows in advanced or developing economies.

We also highlight a flight-for-safety phenomenon when global uncertainty is high or persistent, thus leading foreign investors to redirect FDI to advanced countries, perceived as safe heavens.

Finally, our results suggest that higher financial openness in host countries reinforces the negative impact of global uncertainty on FDI inflows.

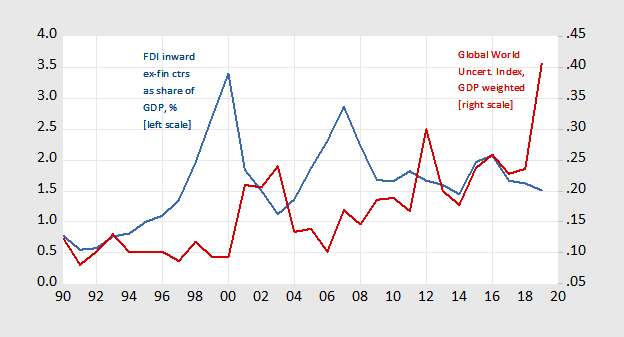

The results are based on a panel data set, but one key finding is illustrated by this time series plot.

Figure 1: Inward FDI as a share of GDP, ex.-financial centers, % (blue, left scale), and Global World Uncertainty Index (red, right scale). Source: JJC (Figure 3), Ahir, Bloom and Furceri.

What’s one real-world implication? In our baseline specification:

Returning to the point estimates of the global uncertainty impact obtained, we can evaluate whether this estimate is economically large by considering a counterfactual. Using the group-specific point estimates, we can consider what FDI inflows would have been, had the level of global uncertainty from 2015 to 2019 been comparable to the one in 2014 (that is 0.18 instead of 0.41). This leads to the results shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4Open in figure viewerPowerPoint

Foreign direct investment inflows significantly dampened by uncertainty. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com] Note: The lines show FDI inflows as percentage of GDP as a simple average across country groups. Marker lines show the expected FDI inflows from 2015 to 2019 in advanced and emerging economies, had the global uncertainty index been comparable with the level observed in 2014.Our estimates imply a large impact on FDI inflows, perhaps unsurprisingly because of the large postulated change in global uncertainty levels. FDI inflows rise by about 1 percentage point of GDP for emerging market economies, and by about 1.5 percentage points for advanced economies.

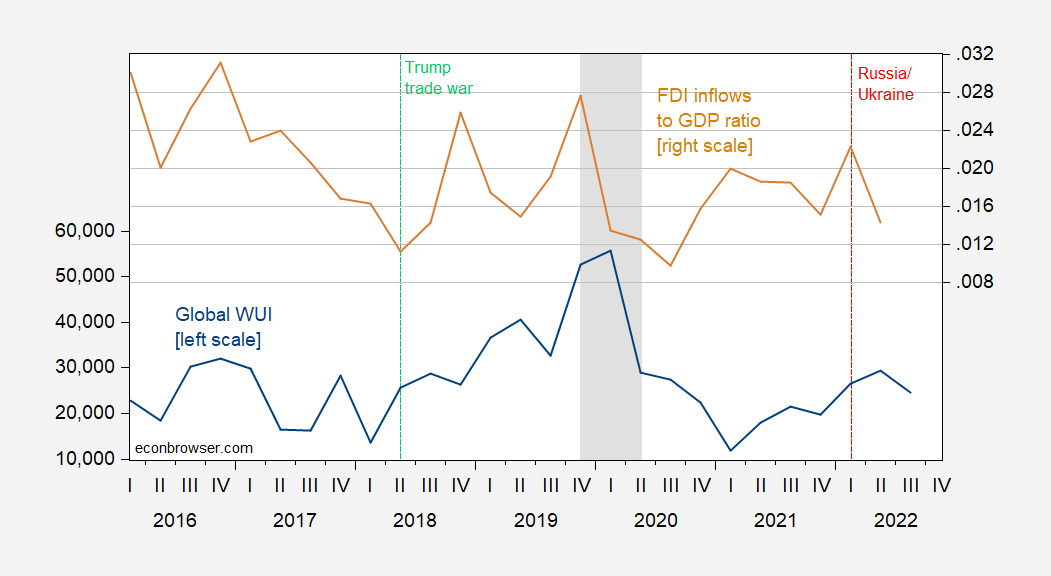

Our analysis extended up to 2019, just before the pandemic. Here’s a picture of global WUI and FDI inflows/GDP since then.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Figure 1: Global World Uncertainty Index (WUI) (blue, left scale), and world FDI inflows to world GDP ratio (tan, right scale). World GDP interpolated from IMF WEO (October 2022). NBER defined US peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: worlduncertainty.com, OECD, IMF WEO October 2022 database, NBER and author’s calculations.

The 2020 spike in WUI (not in the Jardet, Jude, Chinn sample) is associated with a decline in FDI inflows to GDP (although of course income was also falling). The Q2 local peak in WUI after the expanded Russian incursion into the Ukraine is also associated with a decline in FDI inflows.

More By This Author:

China Saber-Rattles (Again)Goods Trade Balance Improves In November

Chinese GDP Growth Over The Xi Jinping Era