What Happens If The Inflation Rate Never Gets Back To 2 Percent?

Image Source: Pixabay

Somewhere in the annals of history, a central banker decided that the non-inflationary world meant that the consumer inflation rate would settle in at 2%. If the rate exceeded that number for a reasonable period, then the central banks would be required to raise their policy rate to cool economic activity. In contrast, sub- 2% inflation rates encourage central banks to keep rates down. We have seen both these strategies at work, first during the 2010-2021 period of inflation, when nominal interest rates settled around zero percent and real interest rates were decidedly negative. As the Covid pandemic swept the world, inflation, especially for consumer goods, took off, followed later by significant price hikes in the services sector. Fighting inflation has dominated central bank efforts worldwide, and only now is there a recognition that rates need to reverse direction in the hope of avoiding recessionary conditions.

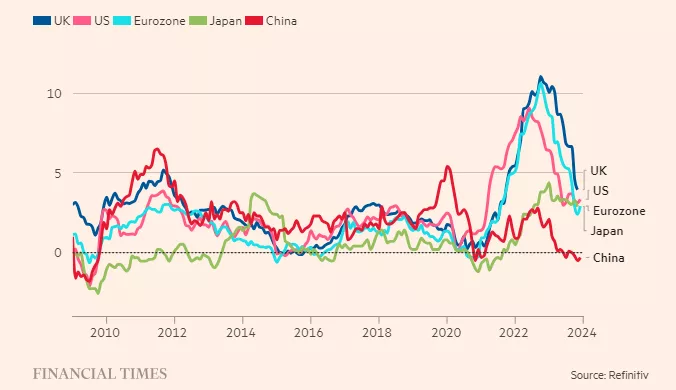

So, where are we now? The Western democracies seem to be settling in at inflation rates around 3 + %, having come down dramatically from peaks of 9-10 % in 2021-22. China remains the only major economy that is now undergoing outright deflation as it copes with adjustments from an over-built real estate market, along with a general slowdown globally. Otherwise, there has been a steady record of consumer prices hovering around the 3+% market, while GDP growth slows to less than 2%.

The Bank of Canada, although adhering to the conventional target of 2%, says it operates within a range of 1% to 3% and thus offers, ostensibly, more flexibility in setting its overnight bank rate. It uses the total consumer price index (CPI)as the most relevant measure of the cost of living.

Without going into technical issues, the Federal Reserve prefers the Personal Consumption Index (PCE) over the CPI. The CPI measures the change in the out-of-pocket expenditures of all urban households and the PCE index measures the change in goods and services consumed by all households. The latter seems to capture dynamic changes in consumer behavior. In general, these two measures move in sync to a significant extent but might vary in the actual price levels. The European Union uses a Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) is a measure of inflation. It reflects changes over time in the prices paid by households for a representative basket of goods and services throughout the region.

Collectively, these central banks have signaled that this current rate cycle has peaked. The Federal Reserve provided a range of projected rates, the so-called “dot plot”. Each Fed official’s projection for the central bank’s key short-term interest rate is marked. The dots reflect what each U.S. central banker thinks will be the appropriate midpoint of the fed funds rate at the end of each calendar year. The Fed Funds Rate now features a total of 0.75 percentage point worth of cuts in 2024. Although the Bank of Canada and the European Central Bank do not release any rate forecasts, investors know that those central bankers will not allow their rates to vary too far from those of the Fed.

Back to my original question. If inflation remains stubbornly at 3% or slightly above, does the Fed dot plot need to be revised, possibly including no rate changes in 2024? Or, are we in a world of 5-5.5% bank rates and inflation at 3-4%---- a new permanent level?

More By This Author:

The Bank Of Canada Needs To Change HorsesThe Bank Of Canada Lives In A World Of Denial

The Mortgage Market Is Contributing To The Decline Of The Canadian Economy