The Bare Minimum

Author's Note: This article discusses the minimum wage. I understand that this is a nuanced and delicate topic, and there are many points I did not address including systemic inequality, education, productivity indexing, and more. If you have thoughts or questions, please leave a comment.

It’s long past time we raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour. The American Rescue Plan will get it done.

— President Biden (@POTUS) February 2, 2021

The Minimum Wage

What will happen if we raise the federal minimum wage?

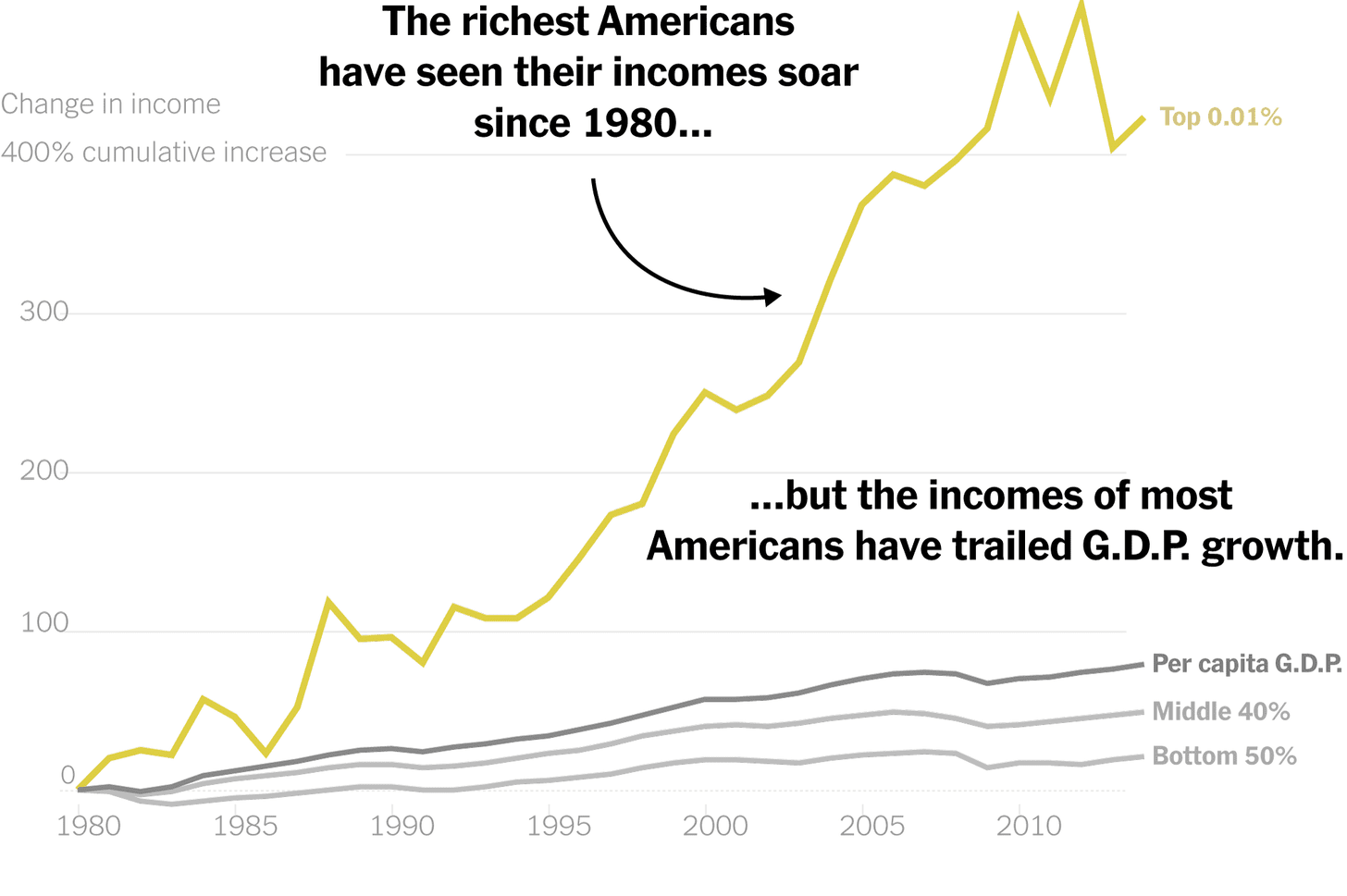

The pandemic has exacerbated the already uneven outcomes between lower-wage and higher-wage workers. Income inequality and the “distribution of prosperity” are at historically high levels, with much of this disparity heavily impacting minority communities.

Source: New York Times

This is a contentious topic, with some arguing of cost-push inflation (a $15 minimum wage will result in a coffee costing $15 too) and some arguing that it won’t change the price of goods or result in mass unemployment – and that raising the minimum wage is one of the first steps to addressing the inequities of our system.

This article discusses:

- The Current Labor Force

- The Structural Deficiency of the Minimum Wage

- The Minimum Wage and the Cost of Production

- The Complexity of the Issue

- Potential Outcomes

TL;DR: Why should we raise the minimum wage?

- Healthier, more stable workers: There is power in being able to afford medical care, health insurance, and safe living conditions. Also, if the workers have children, those children are all to benefit from all of the above – and that compounds over time.

- Alleviating poverty: An increase in the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $12.00 would be the first step to lifting 6.6 million people out of poverty.

- Addressing inequality: “Most low-wage workers are disproportionately women and people of color” and raising the minimum wage would work to reduce earnings inequality for these workers

- Respect for other humans: If this pandemic has taught us anything, it should be that essential workers are truly essential. These workers have been on the frontlines of a raging pandemic, literally putting their lives on the line to keep the wheels of the broader economy turning.

- Investing in the Future: This is not just a short-term fix. This is a long-term approach to fixing the decades of underinvestment in the U.S. population. This is a multi-generational, systemic problem, that must be addressed head-on.

Let’s first look at the labor force and the minimum wage in context.

Overview of the Labor Force:

- 53 million Americans, or almost half of the labor force, earn low wages (a median annual income of $18k).

- 1 in 5 of these workers (32 million) do not have employer-sponsored healthcare.

- Low-wage jobs have increased since the 1970’s while middle wage jobs have declined, exacerbating the increasingly bimodal wealth distribution

The Minimum Wage

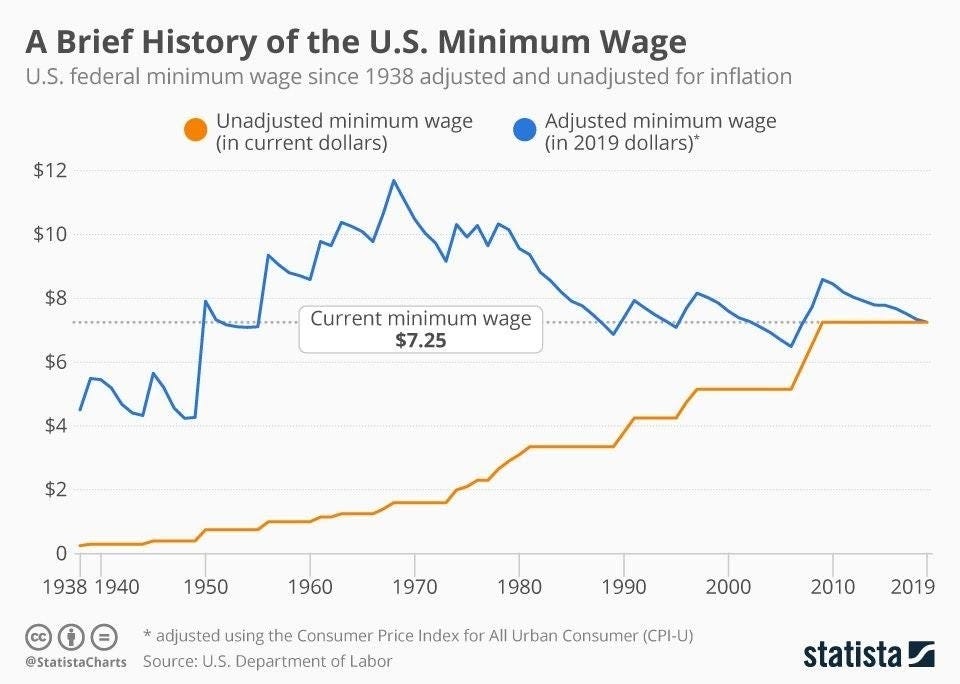

- Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the minimum wage was well above $8 per hour in relative 2019 dollars

- It peaked in 1968 at $11.69 in 2019 dollars

- This is well above the current minimum wage of $7.25 (which has been at $7.25 since 2010)

- Several states have already increased their own minimum wage including California, Massachusetts, and Washington State

- In terms of purchasing power, the minimum wage is worth ~17% less than it was 10 years ago, and ~30% less than the 1968 peak.

- If it moved with productivity growth (like it did up until 1968), the minimum wage would be ~$24/hour.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Source: Statista

The Structural Deficiency of the Minimum Wage

With this historical context in mind, what is the true cost of a too-low minimum wage?

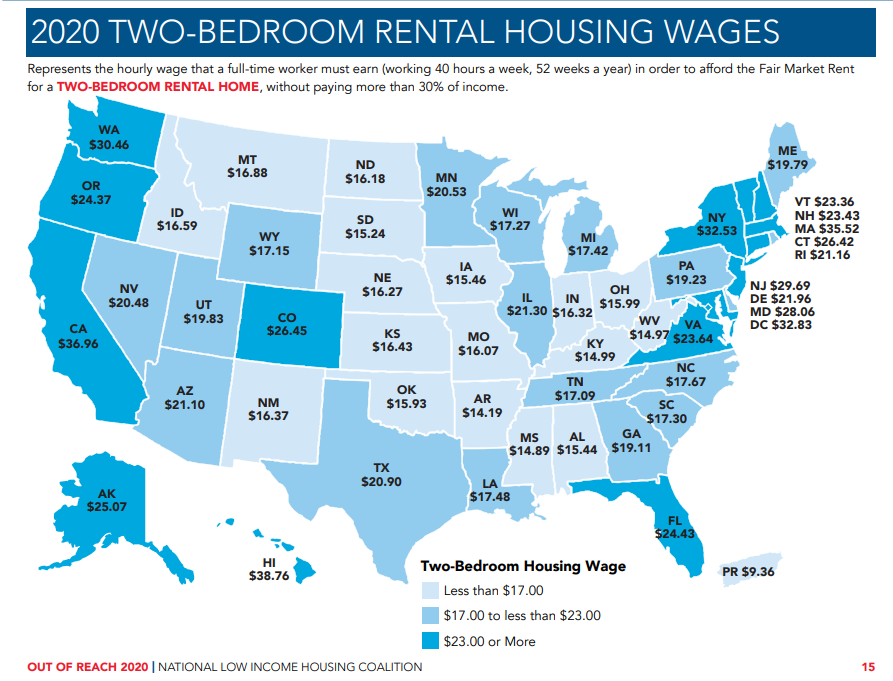

Well, to begin with, there is no place in the United States where a minimum wage worker can afford a two-bedroom apartment, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. This is important as most people need a two-bedroom at some point, as they have kids and seek out larger spaces.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Source: NLIHC

One would have to make $24/hour to comfortably (aka have enough income for food, healthcare, AND housing, etc) to be able to afford a two-bedroom (funnily enough, right in line with the aforementioned “productive wage”) and $20/hour to afford a one-bedroom, compared to the current $7.25 federal minimum wage.

That leaves a gap of ~$17 and ~$13, respectively. Per hour.

In order to make that difference up, one would have to take on at least 2 more minimum wage jobs.

They would have to work nearly 100 hours per week to get a 2-bedroom, and nearly 80 hours per week for a one-bedroom.

We tend to miss the forest for the trees, especially when discussing the unemployment rate. As Martha Ross, a senior fellow at Brookings explains:

“[The unemployment rate] is important, and we shouldn’t lose it. [But] if wages aren’t enough to support yourself, then the low unemployment rate doesn’t mean that people are doing well.”

If someone can’t afford a stable place to live, being a human becomes very hard. When there is a disconnect between security and existence, it becomes much more difficult to function. If you aren’t having your basic needs met, you can’t focus on much else.

And that’s damaging. I’ll circle back to this.

The Cost of Production

People worry that if wages increase in the United States, the cost of goods will increase as well, stating that employers potentially have to pass off increases in cost somehow.

But let’s take Big Macs as an example. They’ve already increased in price, without any increase in the federal minimum wage.

Assuming each burger takes 3 minutes to make, the cost of labor per burger has fallen from 8.7% to 7.3%, assuming that there has been no increase in wages paid since 2013.

Assuming 3 minutes / burger again, if there is an increase in the minimum wage to $15, that means McDonalds would be paying $0.75 of labor per burger, compared to the $0.36 that they are paying under the $7.25 minimum wage.

Cost of labor increases from ~7% of the burger under $7.25/hour to ~15% under $15/hour.

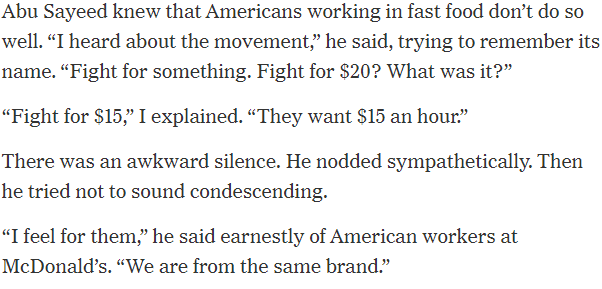

However, in Denmark, McDonald’s employees make $20/hour.

But their burgers are only ~$0.65 more expensive than the U.S. burger, costing $5.60.

Assuming ~3 minutes of labor per Big Mac, that’s $1 of labor per burger, or ~18% of burger cost.

The $15/hr wage in the U.S. is still ~3% cheaper per burger, when compared to Denmark. The New York Times has a piece that highlights the difference between the two countries.

Source: NY Times

I know that comparing Denmark and the United States doesn’t always make sense. They approach the concept of social safety nets and government support very differently. But there is something here – the burger is $0.65 more in Denmark, but workers make $13 more. Considering the U.S. burger has increased by $0.76 – maybe there is some wiggle room in worker wages there too.

We see higher minimum wages in places like NYC and California. In Seattle, the higher minimum wage increase didn’t result in massive employment losses or business shutdowns – rather the opposite.

- Increased Opportunity: It not only saw new restaurants opening, but also employment in those restaurants soaring (of course, pre-Pandemic).

- Stable Price Levels: Researchers found “no overall market basket price changes attributable to Seattle’s minimum wage”.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Source: Ritholtz

But the situation is multi-faceted.

The Complexity of the Issue

McDonalds and other businesses do need to keep prices low. That’s their whole model. Businesses can only absorb so much of an increase in cost, because they do have many stakeholders to respond to. Franchises and small business owners don’t have a lot of financial flexibility.

Businesses can’t outprice their customer base.

Many worry that higher costs of production and higher wage costs will outprice products, as well as workers. Workers could lose their jobs because businesses might have trouble affording the increase in wages.

However, these worries are largely unfounded.

The Cost of Products

Most studies show that prices are not impacted by minimum wage increases.

- MacDonald and Nilsson (2016) note that for every 10% increase in the minimum wage, prices rose by 0.36% (this is a minimal increase)

- Buszkiewicz et al (2018) found that there was “no market basket price changes” from a increase in the minimum wage

The Cost of Employment

Modest, gradual wage increases actually don’t result in a reduction in employment. As Belman and Wolfson highlight in “What Does the Minimum Wage Do”, a review of 15 years of research around the minimum wage:

There is little evidence of negative labor market effects [from an increase in wages]. Hours and employment do not seem to be meaningfully affected.

The article continues:

While not a stand-alone policy for resolving the issues of low income in the United States, the effectiveness of moderate increases in the minimum wage in raising earnings with few negative consequences makes it an important tool for labor market policy.

There is little evidence of an increase in wages hurting employment, according to Belman and Wolfson’s research. The authors conclude that minimum wage is actually a powerful tool to improve equality and outcomes.

Consensus has broadly shifted from the idea that minimum wage hurts employment to the idea that minimum wage has little to no impact on employment effects.

So what should the United States do?

What are the potential outcomes?

- Realizing it’s not a zero-sum game: Providing targeted and intentional assistance is unlikely to create a giant gap somewhere else in the system. If anything, it will create more value down the road, for both the workers and companies.

- Upskilling Opportunities for Workers: There are skills that carry over to growing industries, such as traditional manufacturing and hard tech. The connections are there, they just have to be made – and that can compound over time.

- Increased Innovation: Circling back to my first point – if people have stability, there’s no telling what can be created. Rather than worrying about their next meal, they can focus on their creative passions and pursuits.

- Improved Health: If people can provide for their basic needs, that’s a huge benefit towards health outcomes.

- Targeted Growth: Rather than just paying stimulus (or not paying it at all) these sorts of programs would address problems head on, and pay for themselves over time.

A higher minimum wage is already happening on the local level, which is a good step. But there is work to be done on the Federal level and setting a national standard. Perhaps a flawed example, but just because one state has intense environmental regulations, doesn’t mean that the whole nation is going to benefit from their carbon capture program – it has to be a coordinated effort.

Arindrajit Dube has a strong plan for how the minimum wage could be approached including:

- Use 50% of local area median wage as a starting point (i.e., Los Angeles is going to have a higher minimum wage than Kentucky)

- Index wages to increases in regional CPI to capture cost of living changes

- Encourage coordination among state and local governments

I think often of the paper from ESMT Berlin – “Children who eat lunch score 18 percent higher in reading tests”. Children who have their basic needs met do almost 20% better on their exams. There is also a study that shows if kids have more time to eat lunch, they make better nutritional choices – more time to think, more time to process, better choices are made.

We can extrapolate here.

Stability compounds. Safety delivers returns. Security creates growth.

I realize that this is an extremely nuanced discussion, with value judgements and market measures of utility. There is systemic underinvestment in minority communities, which is where the option for Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC) alongside a higher minimum wage, could further help to supplement.

But it is truly imperative for society to invest in its people. And that begins with a livable wage.

Special thanks to Ashoka Rajendra, Doc Ayomide, Drew Stegmaier, Godiva Golding, Grant Gregory, Kushaan Shah, Jeanette Goon, Joel Christiansen, Lyle McKeany, Rishi Dhanaraj, Ryan Williams, Sasha ...

more

Well, that's a natural result of financialized economy, characterized by serial bubbles and busts in the stock market and elsewhere. The labor participation rate trend isn't really positive.