Is The Federal Reserve 'Too Big To Fail'?

The term "too big to fail" refers to certain businesses whose viability is considered critical to the survival and effective operation of our economic system. These very large businesses are designated as too big to fail because their failure or bankruptcy would have disastrous consequences on the overall economy.

The potential effects are considered to be severe enough, and the costs so unbelievably large, that these businesses are afforded special attention and consideration in the form of bailouts and protection from creditors.

The expenses necessary in order to save a large institution from bankruptcy are considered less than the costs that would be incurred if the institution were allowed to fail. Active application and implementation of both alternatives were prominently featured in the financial crisis of 2008.

But size alone isn't necessarily the principal factor. What government regulators found in Lehman Brothers bankruptcy filing in 2008, was that the biggest banking firms were interconnected to such a large degree, that allowing one of them to fail, could trigger other failures in a sort of 'domino effect'. A series of large institution implosions might very possibly lead to a total financial and economic meltdown.

Even though Lehman was allowed to fail, it was deemed necessary thereafter, to be selective in how each institution's situation was administered. This meant that certain institutions were allowed to fail (Lehman Brothers) while others received special attention and financial help (Merrill Lynch merger with Bank America; JP Morgan Chase re: funds for acquisition of Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual; Morgan Stanley; and Goldman Sachs).

By far, though, the biggest bailout of all, and the biggest fears, centered on American Intentional Group (AIG). Its extensive and intricate involvement in credit default swaps appeared to be so extensive and interrelated to others, that a collapse of the entire financial system appeared ominously possible.

The open jaws of the beast were about to clamp down on the creators of the biggest financial mess in our nation's history.

So the government stepped in. And a collective sigh of relief was heard around the world.

Original estimates of $7-800 billion dollars grew larger before the printer's ink had dried. Even one trillion dollars would not be enough. Make it two; or three.

We can't afford it, some said. The expense is necessary and justified, said others. And some said it wasn't enough.

The government, as usual in situations of such magnitude, put its best foot forward. In solemn declarations, we were treated to a series of explanations about how we had narrowly avoided more serious problems and will all need to pull together.

Afterwards, comes the moral indignation and the cries for punishing guilty parties. The government complies and their efforts spawn a new series of laws and regulations which are termed as acts of reform.

Now let's pay attention to the actual finances of the matter.

When the government announced the initial steps in its efforts to keep things from unraveling, most people focused on the amount itself. How the funds would be provided didn't seem to be as much of a concern.

We are not talking about potentially higher taxes. We are talking about the specifics of funding such large and expensive efforts - now. Do we assume that the government just wrote a check? and planned to collect from us, as taxpayers, later?

Where did the money come from? Was anybody else involved? A sugar daddy?

The amount of money, spent to extricate us (well, not us, not really) from the financial hole we (others) had dug, was created by the Federal Reserve - out of nothing. Here is how it works.

When the government needs money, for any purpose, it issues a specific amount of Treasury securities (bonds, notes, and bills) which corresponds to the amount of money desired. For example, if one hundred billion dollars is needed, The U. S. Treasury issues securities totaling one hundred billion dollars.

The assigned value of the new Treasury securities (in this case one hundred billion dollars) is an addition to the existing supply of money and debases all the money in circulation. It is the electronic equivalent of printing press money.

The money used by investors to purchase the Treasuries, and which is credited to the account of the U. S. Treasury on the day of the auction, is spent almost immediately by the government to pay its expenses. In this way it finds its way back into the system quickly and the existing money supply is now larger by the amount of one hundred billion dollars – the amount of Treasury securities that were issued.

Part of the Fed's efforts known as quantitative easing, or QE, was to credit various primary dealers and troubled institutions with large amounts of money that was available to them to lend or invest, or simply hold on deposit with the Fed.

Also, the Federal Reserve lowered its discount rate. The discount rate is the amount that the Fed charges for loans to member banks who choose to borrow directly from the Fed. The purpose in lowering the rate was to encourage banks to borrow from the Fed and relend the money to others, thus creating a source of funding for economic activity.

In addition, the Fed purchased large amounts of debt securities in the open market. Most of these securities were collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs. This helped support a market for debt securities that was continuously losing value because of defaults by borrowers - auto loans, for example - and the realization that existing lower values of assets, like houses, were not enough to provide the backing for the original loan amount.

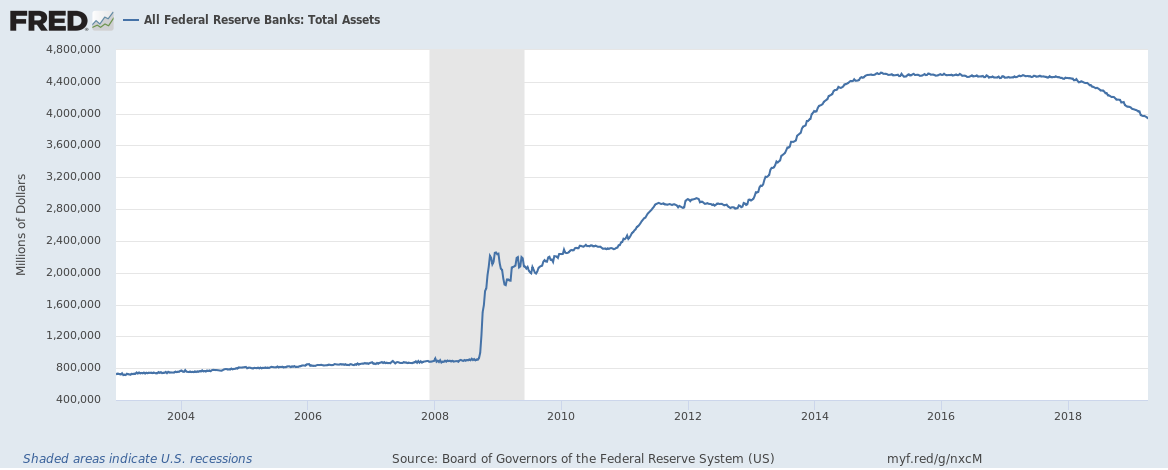

The purchase of these debt securities was not a regular practice by the Fed. Ordinarily, the Fed only held nominal amounts of U. S. Treasury securities on its balance sheet. The huge amounts of debt securities purchased and held by the Fed was different in both size and type.

The chart below shows the rise and then leveling off of total holdings, as well as a subsequent moderate decline in those holdings which has become more pronounced as a result of the Fed's active efforts to divest of these 'assets' over time.

All of the combined efforts by the United States government and the Federal Reserve with regards to the financial crisis of 2008, were funded with dollars that were created by the Federal Reserve. And the dollars were made available in the form of credit. The credit was extended to the U. S. government and to various financial institutions.

By their actions, the Fed eliminated any doubt that they are the "lender of last resort" in this country, and probably the world.

But, a guarantee is only as good as the guarantor. Who stands behind the Federal Reserve? You probably don't want to know the exact answer to that question, so let's defer any explanation that involves conspiracy.

What happens when it all comes undone? If we suddenly found ourselves in the middle of another financial meltdown, will there be somebody, or some institution that can re-guarantee all of the worthless debt that currently floods the world?

Any credibility for the Fed is dependent on their avoidance of a recurrence of 2008. But, unfortunately, it is not up to them, nor is avoidance dependent on their efforts. Another credit collapse is inevitable.

Fed efforts might postpone or delay the dire consequences that await, but things will get a lot worse before they get much better.

The Fed can create unlimited amounts of money and credit if it feels that such action is necessary. They do, of course, feel that it is necessary. And, they have been expanding the supply of money and credit for over one hundred years. But even a lender of last resort has limits to the impact of its activities and functions.

The Federal Reserve is approaching those limits. And there isn't anything they can do about it.

Where is the foundation for the implicit trust and confidence that so many seem to have in governments and central banks regarding their money and their financial affairs?

Kelsey Williams is the author of two books: INFLATION, WHAT IT IS, WHAT IT ISN'T, AND WHO'S RESPONSIBLE FOR IT and more

Probably.