The Demise Of Dollar Dominance

That’s the title I gave for an essay published in the Nikkei today:

[Link to article]

Here’s the text in English:

Every decade, the debate over the dollar’s role as the world’s premier currency returns: will America’s currency be dethroned by another country’s? In the 1970’s, it was the Japanese yen or the Deutsche mark. Then with Economic and Monetary Union, the euro was viewed as a contender. In the last decade, the renminbi took up the role as possible aspirant. Where do we stand in 2022?

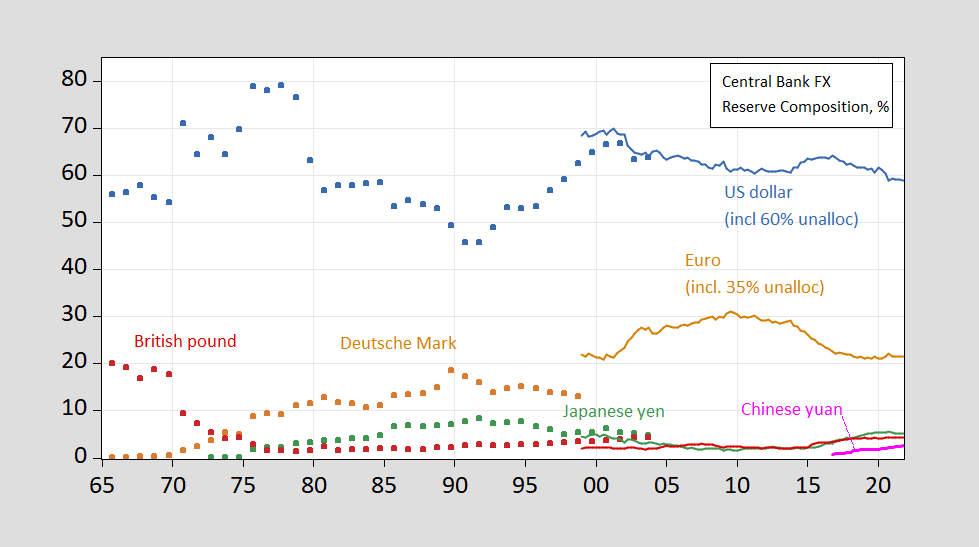

Before answering that question, it’s important to remember that the one that thing has proven true over the past forty years is the durability of the dollar’s primacy, as shown in Figure 1 — through the global financial crisis, and through the covid pandemic. The dollar remains the primary currency in the holdings of central banks around the world. While there is some uncertainty regarding the exact shares held in each currency (since some central banks do not report the composition of their holdings), the dollar accounts for about 60% of total, far above the euro’s share in the low 20’s. Despite the much heralded rise of China’s currency, the renminbi, its share had only risen to 2.6% by the end of 2021.

Figure 1: Share of foreign exchange reserves in USD (blue), Deutsche mark (orange square), euro (orange line), British pound (red), Japanese yen (green), Chinese yuan (pink). Source: Chinn and Frankel (2008), and IMF COFER.

If we look at other dimensions of the a currency’s role – as a unit of account, a medium of exchange and a store of value – it’s not clear that dollar dominance is under serious threat. About 40% of world trade is invoiced in dollars, somewhat more than that in euros. In terms of foreign exchange trading, the dollar remains by far the dominant currency with 88% of 200% total turnover in dollars. In terms of international messaging for financial transactions (i.e., via SWIFT), the dollar remains a leader, accounting for over 40% of activity. The euro follows at about 35%. Why the handwringing, then?

Sanctions Blowback

Doubts over the dollar’s dominance have come as the sanctions regime imposed on Russia has seemingly struck a crippling blow against the economy. It is thought by some that this demonstration of vulnerability would spur other countries to move away from dollar dependence.

Part of the drama came from sanctioning a major power central bank, since the functioning of the monetary authorities were thought to be protected. In this case, the US, along with Western allies, threatened sanctions against financial institutions engaging in activities with Russian banks, including the Central Bank of Russia. But a substantial portion Russian foreign exchange reserves were held in Western central banks. Not only were financial transactions curtailed, the Russian central bank couldn’t access perhaps a $100 billion of its reserves.

This seeming success contrasts with conventional wisdom regarding the efficacy of financial sanctions. Over previous decades, the US had imposed economic sanctions as a means of trying to alter the behavior of other countries, from Cuba to Libya and to Iran. US attempts to induce Iran to come to an agreement on limiting nuclear proliferation included sanctions, some of them termed “smart sanctions” – targeting individuals and industries, rather than whole economies. While the view of sanctions efficacy was more effective in the wake of the short lived achievement of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) involving Iran, there was still skepticism that sanctions could deter – or constrain – further Russian aggression in the Ukraine.

The wholesale damage wreaked upon the Russian economy has cast a new light on sanctions efficacy. The Russian economy is slated to shrink by 30% by the end of 2022. More importantly, the long term impact of cutting the economy from Western technology and imports is likely to set the Russian economy back decades. The ruble has recovered to its pre-war levels, but this seeming resilience is only a surface gloss; the recovery has been achieved by imposing stringent capital controls, restricting the purchase of foreign exchange, and forcing firms to surrender export proceeds earned in foreign currency.

What makes the effect of sanctions all the more surprising is that Russian policymakers had spent the years after 2014 invasion of Ukraine insulating the economy against economic sanctions. In particular, a hoard of foreign exchange was amassed. This all seemingly demonstrated the enormous power afforded the United States by the dollar’s privileged position as the world’s currency.

Will this dramatic demonstration inspire dedicated moves to diversify away from the dollar, in a way that has not occurred in the past? I think the answer is no.

A Farewell to the Dollar?

The first reason I think it unlikely is that it is extraordinarily difficult to move away from using the dollar, along many dimensions. Consider foreign exchange reserves: Central banks tend to accumulate foreign exchange reserves in the currency in which they are earned – either in exports, or in capital inflows. A large share of export earnings in world trade are invoiced in dollars. About 40% of cross border debt is issued in dollars. In order to change the currency shares of reserves away from the proportions in which they are earned, central banks would have to be determined in selling dollars and buying other currencies such as the euro, pound or yen. This would be an expensive proposition to the extent that markets for assets denominated in these other assets are less liquid, and hence harder to get in and out of. In other words, diversifying reserve holdings out of dollars would be an expensive proposition. Countries would have to incur costs over long periods (holding less secure assets) just to be less reliant on dealing in dollars in the event of a conflict

The second reason I think a concerted move from the dollar is not going to happen is because, in some ways, doing so would be taking the wrong lesson from the events of 2022. It is the multilateral nature of the sanctions that have made them so effective, rather than the fact that the US dollar is involved. Western central banks have frozen Russian foreign reserves held with them (only a portion of reserves are held with the Central Bank of Russia), so that only about $60 billion of the $160 billion was accessible at the end of February.

Case in point, China’s policymakers have apparently concluded that, at least in the short term, there is little way to insulate itself from the type of sanctions treatment meted out to Russia (something on their minds considering the elevated tension between China and Taiwan). In a high level meeting of regulators and bankers in April, leaders concluded that such treatment would devastate the Chinese economy, given the innumerable trade and financlal linkages between the West and China. Even now, Chinese firms have carefully refrained from dealing with sanctioned Russian banks, in order to prevent being sanctioned themselves. But it is not the dollar’s dominance, but rather the dominance of Western finance, and financial infrastructure, which drives Chinese restraint.

But What about the Renminbi?

Throughout the 2010’s, China’s ascent was made manifest by its overtaking of the US economy’s size (at least in purchasing power parity terms). It seemed obvious that an international dominant currency was only a matter of time; the inclusion of the renminbi into the IMF’s Speacial Drawing Right (SDR) seemed to signal the renminbi’s (RMB) time had come. Between 2015 and 2020, the CNY rose from nil to 2% of forex holdings. Turnover in CNY rose from 0% in 2001 to 9% (out of 200%) by 2019.

But no currency can become a major international currency as long as strong restrictions on exist on the cross-border transactions. For some time, it looked as if China had opted for a more open international financial regime. However, since the ascendance of Xi Jinping, it seems that greater financial openness – and the reduction in economic autonomy that would attend it – is no longer a priority. By default, then, a path for the RMB for dominance is now foreclosed. The RMB is already an important regional currency, and will become increasingly so, but its path to being the global currency is now blocked.

So What’s Going to Happen

The dollar is going to retain its dominance because network externalities associated with being a key currency are so strong. That dollar dominance is so strong that a rapid erosion is hard to conceive of. That doesn’t mean that other currencies might not rise in importance (e.g., Australian, Canadian dollar, etc.), other systems for clearing and messaging transactions might develop enough to rival the current incumbents. For the next decade, the international currency regime is likely to look much the same as it does now.

Disclosure: None.