The Big Cycle

“…what I learned is whatever successes I had in life had to do more with how I dealt with what I didn’t know than what I know…

“…what I learned is whatever successes I had in life had to do more with how I dealt with what I didn’t know than what I know…

“…the reason I did that book is because there are things that are happening now that never happened in our lifetime before, and I want to be like a doctor who knows many cases of those, but I have to go back and see them in history in order to gain that perspective.

“…There are only a limited number of personality types going down a limited number of paths, which lead them to encounter a limited number of situations to produce a limited number of stories that repeat over time.”

“…So, the question is really the adaptability. Man has a great adaptability, but he — but by neglecting it, then there are consequences… but how far it goes will be a test of man’s ability to adapt to it.”

- Ray Dalio, in an interview with Barry Ritholtz

One mark of true brilliance is the ability to make complex ideas seem simple. I think this is why so many of us fondly remember our early schoolteachers. They helped our young minds learn things (long division, for example) which at the time were new and often either exciting (to some of us) or tiresome or even frightening to some. We admire our teachers because they succeeded.

Ray Dalio’s book on the Changing World Order won’t teach you long division, but you’ll learn a lot. His understanding of great global cycles is systematic, based on hard data applied to real-world events—as you would expect from a successful trader. You don’t beat the markets by imagining things. You look at reality and figure out what it means.

As I noted last week, Ray’s book is a very deep dive. I can only give you a brief summary that still misses some important points. Today I’ll try to explain his “Big Cycle” concept and how he discerned it by looking at history. Next week, we’ll cover what it tells us about the near future.

Wealth and Power

I talk often about how forecasting (economic or other kinds) is valuable whether it proves accurate or not. The process of making a forecast, and the thinking that goes into it, has benefits beyond just telling you what to expect.

(The obvious and huge exception are those “forecasts” which interpret the facts to reach a desired conclusion. That’s not forecasting! It’s why I am suspicious of all models until I look at the assumptions creating them.)

Dalio recognizes this, too, as he says early in the book.

“While the curiosities and concerns that I described earlier pulled me into doing this study, the process of conducting it gave me a much greater understanding of the really big picture of how the world works than I expected to get, and I want to share it with you. It made much clearer to me how peoples and countries succeed and fail over long swaths of time, it revealed giant cycles behind these ups and downs that I never knew existed, and, most importantly, it helped me put into perspective where we now are.”

That’s really the definition of “macro” thinking, and it led Dalio to this insight. (The bold is his, not me. He uses bolding a lot in his book.)

“The biggest thing affecting most people in most countries through time is the struggle to make, take, and distribute wealth and power, though they also have struggled over other things too, most importantly ideology and religion. These struggles happened in timeless and universal ways and had huge implications for all aspects of people’s lives, unfolding in cycles like the tide coming in and out.

“I also saw how, throughout time and in all countries, the people who have the wealth are the people who own the means of wealth production. In order to maintain or increase their wealth, they work with the people who have the political power, who are in a symbiotic relationship with them, to set and enforce the rules. I saw how this happened similarly across countries and across time. While the exact form of it has evolved and will continue to evolve, the most important dynamics have remained pretty much the same. The classes of those who were wealthy and powerful evolved over time (e.g., from monarchs and nobles who were landowners when agricultural land was the most important source of wealth, to capitalists and elected or autocratic political officials now that capitalism produces capital assets and that wealth and political power are generally not passed along in families) but they still cooperated and competed in basically the same ways…

“Over time, this dynamic leads to a very small percentage of the population gaining and controlling exceptionally large percentages of the total wealth and power, then becoming overextended, and then encountering bad times, which hurt those least wealthy and least powerful the hardest, which then leads to conflicts that produce revolutions and/or civil wars. When these conflicts are over, a new world order is created, and the cycle begins again.”

That’s the Big Cycle in a nutshell. People struggle to gain wealth. Some succeed and establish a new order. Eventually the wealth-holders mishandle it. Conflict follows, the old order falls and a new one rises. Rinse and repeat.

Relative Standings

Dalio isn’t the first to recognize that sequence, but he goes deeper than others in analyzing what determines it. He sees 18 quantifiable measures. I won’t describe them all in detail but they’re things like education, trade, economic output, and military strength. It is easy to nitpick any of these factors, or how he measures them, but that doesn't change the big picture. And the big picture is what we should be focused on.

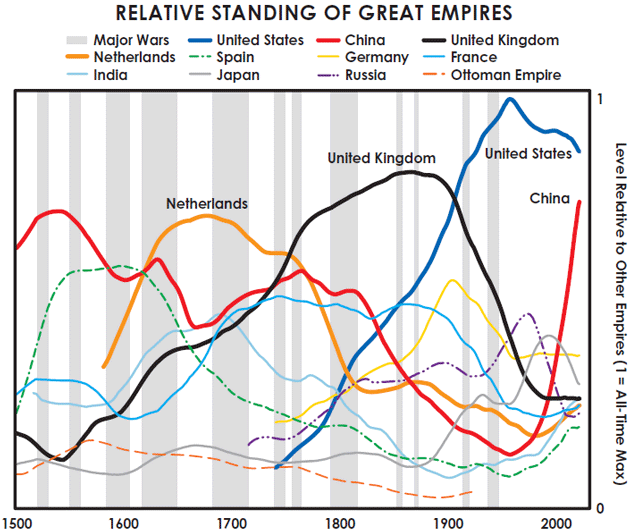

Combining the strength or lack of those determinants let Dalio create a quantitative score or “Power Index” for great powers and empires over time. He shows it graphically in charts like this.

Source: Ray Dalio

The solid lines depict the rise and fall of what Dalio considers the four most important empires since 1500: the Dutch, British, American, and Chinese. (If I were interviewing Ray, I would ask why not start with Spain as their pieces of eight were clearly a global currency, long after they had declined. Just personally curious.)

The chart shows how China dominated (by Dalio’s scoring) in the 1500s, only to be surpassed by Spain and then the Netherlands. China’s decline continued and then accelerated in the 1800s. Meanwhile the UK steadily gained power, breaking above the others in the 18th century and holding the lead for about 200 years.

From its founding, the US rose faster than any other power previously seen, reaching the top in the 20th century and particularly around World War II. And now? The US seems to have peaked and is slowly declining while China is rising fast. (More on that next week.)

Rise and Decline

Dalio goes on to look at empires by their gain and loss of his scoring factors, or “determinants.” This is important so I’ll quote him at length. (Bold by Dalio.)

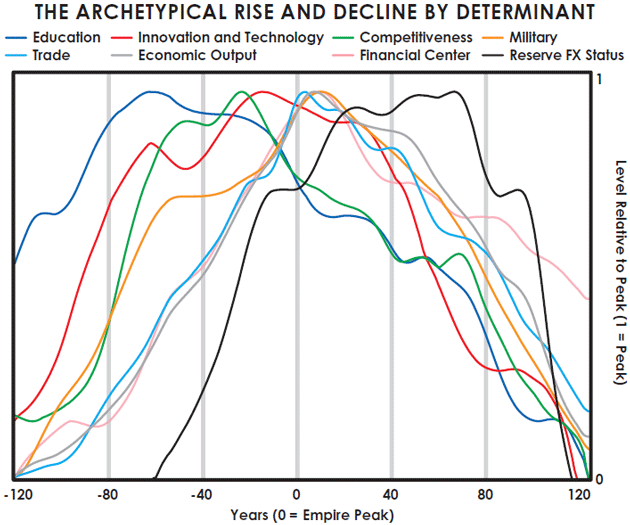

“The single measure of wealth and power that I showed you for each country in the prior charts is a roughly equal average of 18 measures of strength. While we will explore the full list of determinants later, let’s begin by focusing on the key eight shown in the next chart: 1) education, 2) competitiveness, 3) innovation and technology, 4) economic output, 5) share of world trade, 6) military strength, 7) financial center strength, and 8) reserve currency status.

“This chart shows the average of each of these measures of strength across all the empires I studied, with most of the weight on the most recent three reserve countries (i.e., the US, the UK, and the Netherlands).

Source: Ray Dalio

“The lines in the chart do a pretty good job of telling the story of why and how the rises and declines took place. You can see how rising education leads to increased innovation and technology, which leads to an increased share of world trade and military strength, stronger economic output, the building of the world’s leading financial center, and, with a lag, the establishment of the currency as a reserve currency. And you can see how for an extended period most of these factors stayed strong together and then declined in a similar order. The common reserve currency, just like the world’s common language, tends to stick around after an empire has begun its decline because the habit of usage lasts longer than the strengths that made it so commonly used.

“I call this cyclical, interrelated move up and down the Big Cycle. Using these determinants and some additional dynamics, I will next describe the Big Cycle in more detail. But before I start, it’s worth reiterating that all of these measures of strength rose and declined over the arc of the empire. That’s because these strengths and weaknesses are mutually reinforcing—i.e., strengths and weaknesses in education, competitiveness, economic output, share of world trade, etc., contribute to the others being strong or weak, for logical reasons.”

That chart really captures the pattern. It’s set so Year 0 is the average empire’s peak. Notably, the path to empire status begins with education. What is considered “educated” has changed over time, of course, but it’s a necessary condition. And note how a falling education score is the first sign of decline. That should concern us now, as we’ll discuss next week.

Changing Orders

Combining the Big Cycle’s three phases produces a recognizable pattern: rise, top, and decline. Dalio portrays it like this:

Source: Ray Dalio

Each phase has a particular set of cause/effect events. One thing leads to another.

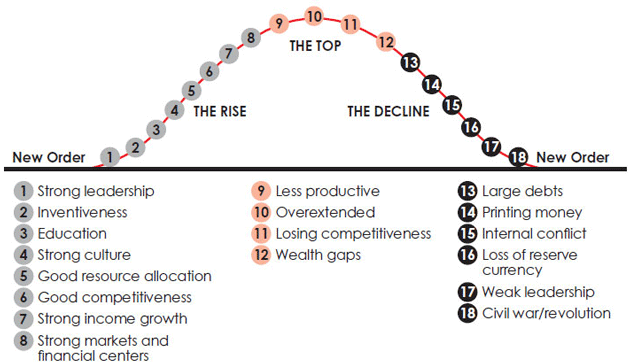

Great powers arise first from strong and capable leadership, which comes from strong education, character, civility, and work ethic. These promote social order and encourage people to work together, enhancing their productivity so they can innovate and invent new technologies. The new technologies make the empire more competitive and give it a rising share of world trade. The resulting trade routes and relationships need protection, so rising empires also build their military strength.

All these accomplishments combine to give the rising power strong income growth. They develop capital markets that fund further innovation by helping people convert their excess income into investments. This makes others want to use the country’s currency, giving it “reserve currency” status.

The empire-building phase is wonderful, but eventually cracks appear.

Higher income makes the country’s workers more expensive and less competitive compared to those elsewhere who will work for lower wages. People in other countries also copy the leading power’s methods and technologies, further reducing its competitive edge.

Citizens of this great power tend to assume, not unreasonably, their success entitles them to enjoy more leisure time, which leads to lower productivity. This typically develops as the generations who struggled earlier in the cycle are replaced by those who know only good times.

The country’s success promotes excessive confidence in the future, which manifests as more debt and asset bubbles. The wealth—much of it illusory—flows disproportionately to the top, producing inequality and conflict. This stays limited as long as living standards keep generally rising.

Meanwhile, the country builds up large debts with foreign lenders. This weakens the currency and external debt rises even more, much of it from poorer countries with higher savings rates. Eventually foreigners lose willingness to lend more or even hold the currency. That’s where the decline phase begins.

The choice becomes debt default vs. inflation (printing money), and most countries choose inflation. Internal conflict and political extremism rise, and wealthy people begin to flee until the economy shrinks.

It gets worse from there, and here again I want to share this in Ray Dalio’s words.

“As conflict within the country escalates, it leads to some form of revolution or civil war to redistribute wealth and force the big changes. This can be peaceful and maintain the existing internal order, but it’s more often violent and changes the order. For example, the Roosevelt revolution to redistribute wealth was relatively peaceful, while the revolutions that changed the domestic orders in Germany, Japan, Spain, Russia, and China, which also happened in the 1930s for the same reasons, were much more violent.”

This is bad enough, but the real, earth-shaking change happens when the leading power faces these internal problems at the same time as an external challenge arises, typically from a rising rival power. The rival seeks to exploit the leading power’s domestic conflicts for its own advantage.

At this point, the declining power’s leadership must choose between fighting and retreating. Fighting is always expensive and can be destructive. Fighting amid poor economic conditions and internal conflict is especially hard.

The result is usually a shift in power that realigns the world order. That’s the end of the Big Cycle. The sequence ends up looking something like this:

Source: Ray Dalio

Dalio’s indexes show the periods of conflict, when leadership transitions from one power to the next, typically last 10‒20 years. The more stable eras preceding it are usually 40‒80 years. So, the Big Cycle keeps leading powers in the top position roughly 50‒100 years.

If World War II marked the last such transition, the world is right now approaching the Big Cycle’s outer bound.

Dalio has been tracking today’s powers using the same methodology. Next week, I’ll show you where we are now in Dalio’s models. But first!

The Future of Energy

Long-time readers will know that I am bullish on energy (oil and gas in particular), precisely because the ESG movement, including numerous governments, is limiting both the amount of money and places that can be drilled for oil and gas. Economics 101 says that if you reduce a supply of something that has an increasing demand the price is going to rise. Felix Zulauf and others at my conference were talking about $120‒$150 oil next year. In a normal world, that shouldn't happen, yet it is. I am taking advantage by becoming a partner in an oil operating program—a rather large change for me, as I had to close my broker-dealer firm in order to do so.

For those with true risk capital, I would invite you to see what we are doing at King Operating. We are physically drilling for oil and gas in older, underdeveloped fields planning to improve their value. Typically, the older fields were all vertical wells, but you can improve the value of that old field by using modern technology and doing horizontal drilling and fracking. It is similar to buying an older apartment complex in a great neighborhood, upgrading and renovating it, raising rents and then selling it to someone who wants to be in the apartment management business.

More By This Author:

Are Bond Yields High?

Cyclical Forces

Why Uranium Prices Are Skyrocketing