Sanctions Are The Swing Factor In Venezuela’s Oil Comeback

Image Source: Pixabay

After the latest political shock in Venezuela, speculation has surged over the prospects of a recovery for the country’s oil industry. On paper, Venezuela still holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves. In reality, production remains a fraction of what it once was.

How quickly Venezuela’s oil production ramps up will depend in part on what happens with sanctions. But Venezuela’s collapse did not begin with sanctions, nor can sanctions relief alone undo the damage. However, that could have a significant short-term effect.

The country’s oil decline has two primary elements. One is structural damage that began years earlier and will take many years to repair. The other is sanctions-driven disruption that arrived later and shut in barrels much more quickly. Understanding the difference is essential to understanding what might come next, and why sanctions will likely impact Venezuela’s oil future in the near-term.

The Structural Collapse Came First

Venezuela’s oil decline traces back to the 2007 expropriations. That year, the government forced foreign operators into minority positions and seized assets when companies such as ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil rejected the new terms.

These were not simple oil fields. The Orinoco Belt is among the most technically demanding heavy oil regions in the world. Sustaining production requires advanced reservoir management, steady diluent supply, and multi-billion-dollar upgraders to make the crude usable. When foreign operators left, they took future investment capital, technical expertise, operational discipline, and project management systems.

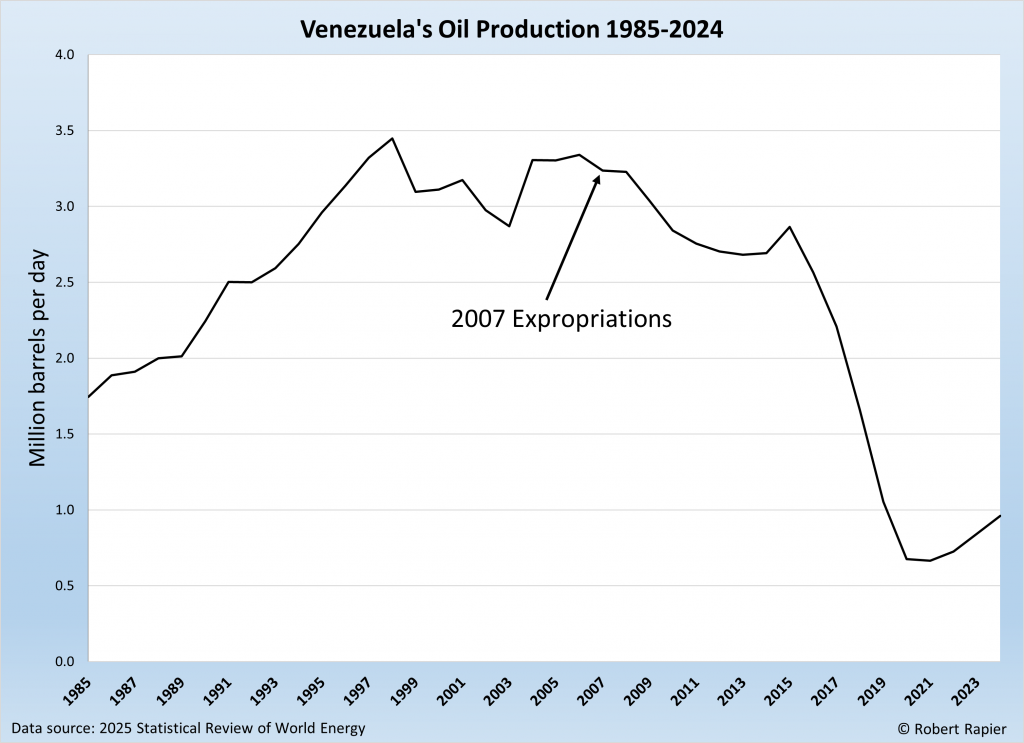

Venezuela’s state‑owned oil company, PDVSA, was awarded the assets but not the capabilities. Maintenance deteriorated. Equipment failed. Skilled workers left. Production began falling years before oil sanctions were imposed, a trend clearly visible in the following graphic.

The steep decline in Venezuela’s oil production after 2015 was driven by the internal collapse of PDVSA, which was marked by political purges, mismanagement, loss of technical staff, and the deterioration of critical infrastructure.

This damage cannot be reversed quickly. Rebuilding infrastructure and restoring a technical workforce is a multi-year effort even under stable political conditions.

Sanctions Hit Later and Accelerated the Decline

The second layer arrived in January 2019, when the United States sanctioned PDVSA directly. Earlier sanctions targeted individuals and had little impact on production. The 2019 measures were different.

They cut off Venezuela’s largest customer, restricted payments, blocked diluent imports, and complicated shipping and insurance. Heavy oil that could have been produced became stranded almost overnight.

Without diluent, crude could not move. Without U.S. refiners, Venezuela lost its most natural market. Without reliable payment channels, joint ventures struggled to operate.

By late 2025, U.S. sanctions and shipping restrictions had severely disrupted Venezuela’s exports. Reuters reported that tanker movements nearly halted after U.S. interdictions, and Vortexa data showed a 36% drop in December alone.

But this is the portion of the decline that could reverse faster. Wells shut in for commercial reasons can restart. Joint ventures can normalize operations. Diluent flows can resume. That would not restore Venezuela to its former peak, but it could produce a meaningful short-term increase.

Chevron’s Structural Advantage

If sanctions ease, Chevron stands apart. It is the only major U.S. oil company that never fully exited Venezuela. Through exemptions, Chevron maintained joint ventures, kept personnel on the ground, and preserved operational continuity.

That continuity is important. Chevron does not need to renegotiate entry terms or rebuild relationships. It needs a clearer commercial framework. But if sanctions ease, Chevron can scale faster than any other Western operator because it never lost its foothold.

ConocoPhillips and the Compensation Question

ConocoPhillips occupies a very different position. It was expropriated in 2007 and later won an $8.7 billion arbitration award, plus interest, for seized investments in the Orinoco region.

The ongoing Citgo sale is one pathway for recovery. If meaningful compensation is secured, re-entry becomes possible. ConocoPhillips was once a top-tier Orinoco operator, but unlike Chevron, it would be rebuilding from the ground up.

Further, ConocoPhillips is a fundamentally different company today than it was in 2007. After the 2012 spinoff of Phillips 66, ConocoPhillips became a pure‑play exploration and production company, no longer an integrated major. And it redirected a significant portion of its long‑cycle, heavy‑oil investment portfolio toward Canada after exiting Venezuela. It may therefore have no interest in re-entering the country.

Why Sanctions Still Matter Most

How quickly could Venezuela’s oil sector rebound? It depends on which layer is being discussed.

Structural damage will take years to repair. Sanctions relief cannot change that. It will likely take a decade or more in the best-case scenario for Venezuela’s oil production to rebound to pre-2007 levels.

But barrels shut in for commercial and logistical reasons could return much faster if restrictions ease. That is why sanctions remain the wildcard. They will not restore Venezuela to three million barrels per day, but they could unlock a noticeable short-term increase.

Over the long term, recovery requires political stability, credible contracts, and tens of billions in investment. In the near term, the most important variable is simpler.

Venezuela’s immediate oil future hinges less on geology than on whether the sanctions landscape changes.

More By This Author:

How Oil Shaped Venezuela’s Economic And Political CollapseEnergy Outlook 2026: When Oil Is Plentiful And Power Is Scarce

The Top 10 Energy Stories Of 2025

Follow Robert Rapier on Twitter, more