Origins And Challenges Of A Strong Dollar

That’s the title of an op-ed appearing in Nikkei newspaper (日本経済新聞):

Chinn, as translated, in The Nihon Keizai Shinbun.

Over the past four years, the US dollar has exhibited noticeable strength. The dollar appreciated 17% in inflation adjusted terms from mid-2014 to the eve of the election; upon the election of Donald J. Trump, the dollar again jumped another 5% in anticipation of fiscal stimulus and the Fed’s interest rate response. Throughout 2017, as the Trump Administration struggled to deliver on tax cuts and an infrastructure program, the dollar faded – only to surge with the passage of the tax plan, and the Fed’s stated intent to raise interest rates. The dollar now stands 20% stronger than it began its ascent.

The sustained appreciation of the dollar, combined higher interest rates, has placed tremendous stress on the global economy. And even more stress on the emerging market economies. Is there hope for relief in the near future? It’s hard to see how. Should the US economy slow, the dollar will depreciate, but it’s a race – between the US slowdown and the rest of the world. And should the world go into recession, the US dollar will likely serve as the safe haven currency, appreciating rather than depreciating further.

What could avert a continued strong dollar? It’s important to realize that the collision of fiscal and monetary policy is not inevitable. Had the Republican coalition not unleashed a supremely irresponsible fiscal program comprising massive tax corporate tax cuts and loosening budget constraints, the Fed would not have had to embark on such a vigorous program of monetary tightening. Almost as damaging, if not more, was the heightened policy uncertainty engendered by Mr. Trump’s erratic pronouncements regarding tariffs and other trade policies. The chain of events and consequences follows.

1. The Dollar’s Ascent

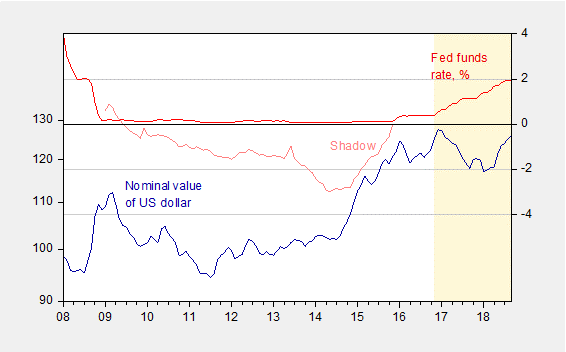

The dollar began its rise in mid-2014. It is hard to understand this event in the context of conventional economic measures, as the most reliable determinant of the dollar’s value is the interest differential. With the Fed funds rate stuck at the zero lower bound from the end of 2008 to the end of 2015, it is hard to discern this effect. However, using the shadow Fed funds rate, which is inferred from the from longer maturity bond rates, there is a more pronounced positive relationship between US interest rates and the dollar’s value (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Nominal value of US dollar against a broad basket of currencies (blue, left scale), and Fed funds rate, % (red/pink, right scale). Shaded area denote post-election period. Source: Federal Reserve, Jin Cynthia Wu and Fan Dora Xia.

The dollar’s more recent uptick corresponded with Mr. Trump’s election in November of 2016. Anticipation of a large tax cut, elevated military expenditures, and implementation of a large infrastructure spending program naturally led to expectations of a stronger dollar as anticipation of a boom in domestic spending and tightening monetary policy developed.

Contrary to Mr. Trump’s assertions, Fed policy has not been “crazy”, nor has it been “too cute’. In fact, an utterly conventional Taylor rule suggests pretty much exactly the observed increase in the Fed funds rate. For instance, assuming a variable real natural rate, and the Fed’s estimate of the output gap, the implied Fed funds rate looks a lot like the actual, as shown in Figure 2. And, if anything, other specifications would suggest an even faster pace of tightening.

Figure 2: Actual Fed funds rate (dark blue) and implied (green), using Taylor rule with PCE deflator target of 2%, one-sided Laubach-Williams estimate of real natural rate, Board of Governors one-sided estimate of potential GDP. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

It goes without saying that continued economic growth will almost assuredly prompt further interest rate increases – a point verified by the FOMC dot plots, and hence corresponding strength in the dollar.

2. The Dollar as a Safe Asset

Is there any possibility of a respite from dollar appreciation? As soon as the US economy starts to slow, the Fed will relent, and the dollar will weaken. However, a full-fledged recession in the world economy could stymie that depreciation; as risk appetite declines, dollar assets – particularly US Treasurys – become more attractive. This happened in the 2008 financial crisis, even though the United States was the epicenter of the financial crisis; capital flowed to the US because Treasurys were viewed as the safest asset.

The likelihood of a US, let alone global, recession seems low given the recent reports of rapid growth – 3.6% annualized in the third quarter. But the tax cut has set up the conditions for a more marked deceleration – albeit from a higher level – than would have been the case without stimulus. Slowing business fixed investment, a forward looking variable, is suggestive of an imminent slowdown.

3. Emerging Market Economies under Stress

There are a confluence of events driving the incipient crises in the emerging markets. The end of the commodity supercycle is signaling tougher times ahead for commodity exporters. That was also true in 2014, when the “taper tantrum” roiled emerging markets. What makes the current situation so difficult is that the dollar is strengthening at the same time that interest rates are rising. Recent work by Joshua Aizenman, Menzie Chinn and Hiro Ito demonstrates that emerging market pressure, as measured by declines in foreign exchange reserves, currency weakening, interest rate increases or combinations thereof, is strongly affected by these two phenomena. And of them, dollar strengthening is the more stressful.

While countries experiencing political turmoil are most obviously suffering (e.g., Turkey), other emerging market economies will inevitably experience similar challenges the longer high interest rates and a strong dollar persist. How well they will fare will depend on the policy choices they have, and are, making regarding exchange rate regimes, capital controls, and macroprudential measures. The greater reserves, the less foreign currency denominated debt, the more resilient.

4. What Can Be Done?

Given the fact the tax cut is in place, and the path of monetary tightening seemingly set, is there an opportunity to mitigate the effects of the dollar’s appreciation? The Fed is constrained from relenting by the fiscal authority’s recklessness. However, the administration could eschew further spending programs, as in a new infrastructure program; political realities and political incompetence in any case makes that outcome unrealistic.

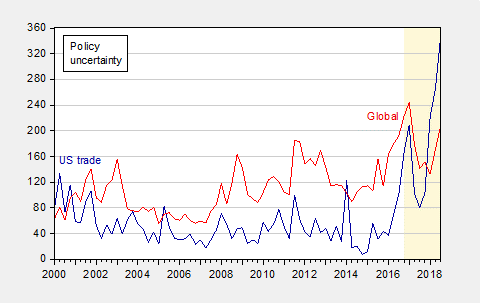

A part of emerging market stress is entirely avoidable: reducing induced policy uncertainty. The greatest influence comes from US trade policy uncertainty. As shown in Figure 3, Global uncertainty is driven by US trade policy uncertainty, a seemingly deliberate outcome of Mr. Trump’s helter skelter approach to negotiating the multilateral trade regime.

How much of the current emerging market stress is due to policy uncertainty? That’s hard to quantify, but uncertainty regarding US trade policy certainly seems correlated with measured global uncertainty (see Figure 3). Policy uncertainty in the emerging market economies should depress business fixed investment activity, and worsen their balance of payments positions. If the effect is sufficiently large, the uncertainty US policymakers are inflicting on the world will rebound upon the US, in depressed exports.

Figure 3: US trade policy uncertainty index (blue, left scale), and global economic policy uncertainty index (red, right scale). Shaded area denote post-election period. Source: Baker, Bloom and Davis, at policyuncertainty.com.

Should emerging market countries be forced to allow their currencies to depreciate en masse, the dollar would tend to rise even further, exacerbating the stresses on emerging market economies, particularly those burdened by high levels of dollar denominated debt (Argentina, Brazil, Turkey).

It’s unlikely the Fed, let alone the administration, will take into account the travails of emerging markets in formulating policy. Hence, hopes that macroeconomic policies will be moderated should be restrained. On the other hand, lots of unnecessary distress can be avoided by simply pursuing a less confrontational trade policy.

Disclosure: None.

Add to all this, China won't be around to pick the USA up from the next Great Recession and we can see how reckless Trump is with the fate of the world.