On China, And Preventing The Financial Runs Of August

Reasoned analysis and careful decisionmaking is required.

The Chinese Context

The global meltdown in equity markets certainly concentrated minds. But, as I observed before, I think it’s important to keep in mind the overall context in China, laid out by Jim in his post yesterday. Here are a few additional graphs, relating to GDP growth and industrial production.

Figure 1: Q/q Chinese GDP growth. Source: NBS via TradingEconomics.

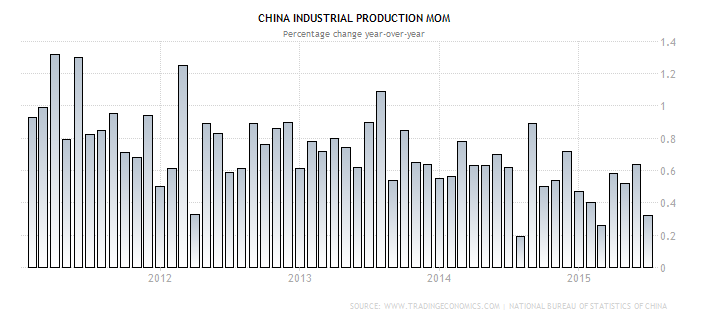

Figure 2: M/m Chinese industrial production growth. Source: NBS via TradingEconomics.

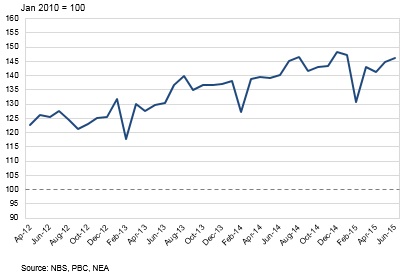

Of course, in China, statistics are difficult to interpret. An alternative indicator, looked to by those particularly wary of official statistics, is the Li Keqiang indicator, an unweighted average of electricity consumption, rail cargo volume, and bank lending (Jim shows the individual components of electricity and railway freight in his post).

Figure 3: Li Keqiang index. Source: World Economics.

No collapse, but surely not vigorous growth. Additional indicators here, here, and OECD.

One key point to remember about forecasting the Chinese economy is that – in my view – the politics matters more than the economics. That is economics is secondary to primacy of the Party. And that primacy depends on perceived legitimacy due to improving economic fortunes. Hence, Chinese policymakers will do what it takes to “satisfice”, i.e. hit a minimum growth level, even if it delays achieving the longer term goals of rebalancing the economy.

In this sense, I think Scott Sumner’s views on the impact of policy is more relevant in China than in the US. Recall, Professor Sumner believes fiscal multipliers are zero because the Fed will adjust its policies to hit a certain target output rate. I’ve never subscribed to this view, but I think it kind of describes the Chinese approach to macro policy: it will adjust policies to make sure it hits minimum level of output viewed as consistent with social stability.

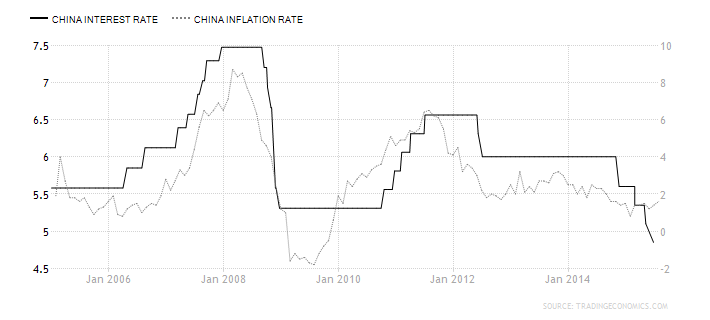

You can see this in the aggressive moves in monetary policy to date:

Figure 4: People’s Bank of China base rate (left scale) and year-on-year CPI inflation rate (right scale). Source: PBoC and NBS via TradingEconomics.

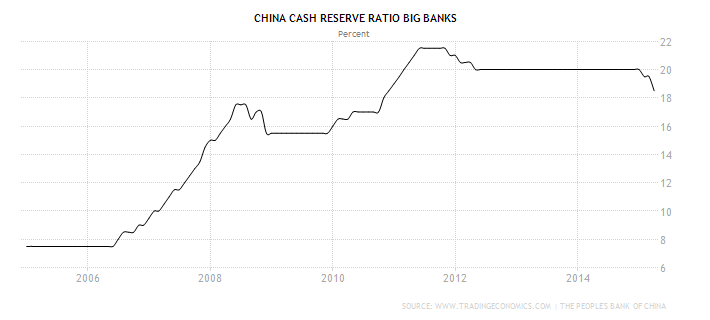

Figure 5: People’s Bank of China cash reserve ratio for large banks. Source: PBoC via TradingEconomics.

Obviously, China has room to loosen monetary policy (as well as exchange rate policy). Inflation is low (and PPI inflation is negative), and the PBoC could further reduce interest rates and the reserve ratio (which it’s indicated it will do).

Implications for the World

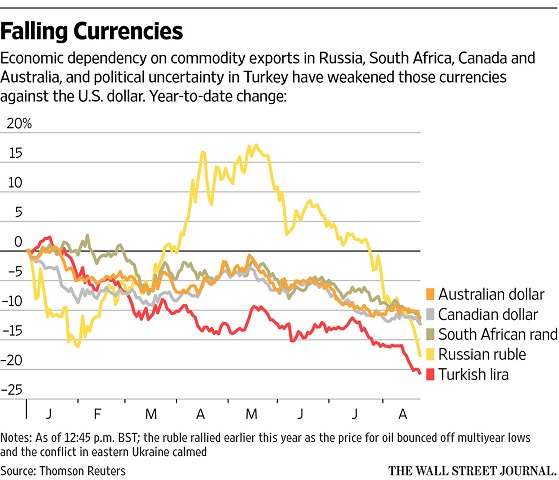

Commodity prices, which have been driven by China’s business cycle, have come down as expectations of growth decline. If my assessment of Chinese policymaker priorities are correct, growth should not slow too much more, putting a floor on commodity prices. I hope that’s correct, because commodity exporting emerging markets have been for years buoyed by Chinese demand. Should my (political) assessment prove wrong, then we should expect a lot more stress on emerging market currencies and foreign exchange reserves (even more than documented in this post).

Figure 6: Falling Currencies. Source: WSJ.

I anticipate further shifts of funds to US safe assets as herd behavior takes hold. [1] In this sense, my biggest fears surround the potential runs of August. This is where US policy comes into play.

What Should the US Do?

A couple of years ago, Barry Eichengreen asked “Does the Fed Care about the Rest of the World?” His answer was – sometimes.

…[T]his longer perspective is a reminder that just because the Fed has not attached priority to international aspects of monetary policy in the recent past is no guarantee that it will not do so in the future.

My hope is that this time around, the Fed does put higher weight on the rest of the world. I’ve already recounted the reasons why the Fed shouldnot raise rates on the basis of domestic factors (a persistent output gap). And the dollar appreciation has already depressed aggregate demand, as discussed in this post. There is no need for a rapid tightening of monetary policy.

In addition, I would say US and Chinese policymakers have to tread very careful. Irresponsible calls to cancel state visits, or to impose sanctions because of vague allegations of plots to undermine the US (as in this case) carry the risk of sparking even greater global financial turmoil.

With the world economy running on one and a half engines – the US and (kind of) Europe – further financial stress due to Fed tightening (or bellicose political language) is the last thing we need.

Disclosure: None.

Comments

No Thumbs up yet!

No Thumbs up yet!