Where Is The Money Going?

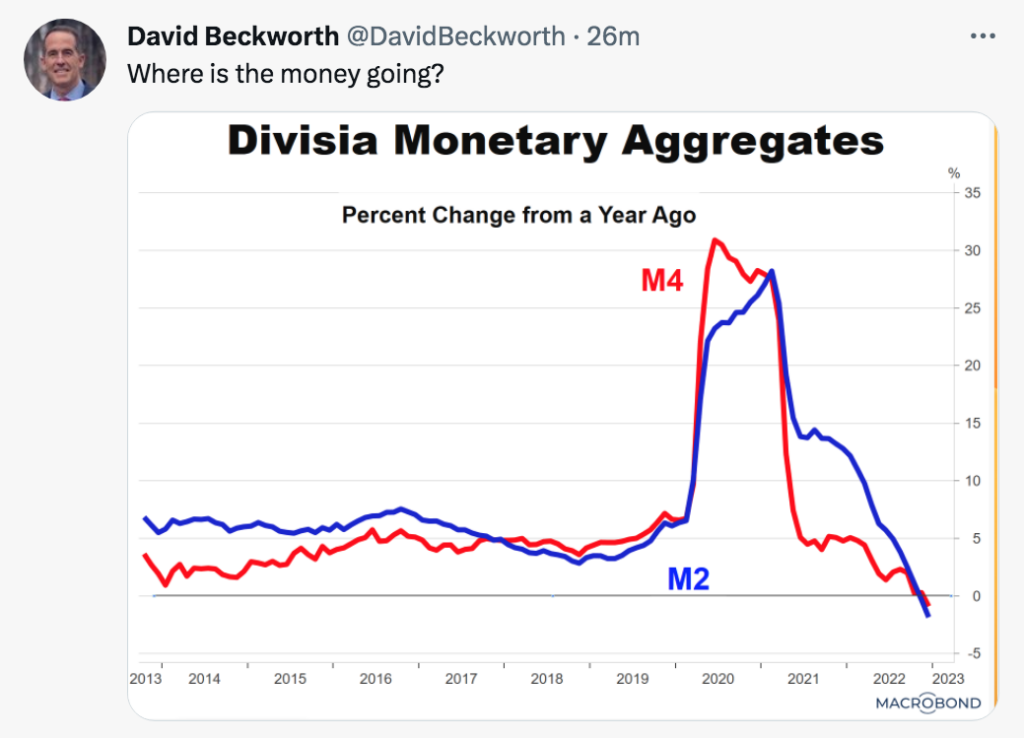

This David Beckworth tweet asks an interesting question:

If inflation had stayed stable at 2%, this question would have a simple answer. In that case, changes in the money supply growth rate would reflect changes in real money demand. In other words, the Fed would have been accommodating shifts in money demand with equal changes in the money supply growth rate.

It would also be easy to provide a simple explanation if inflation were perfectly correlated with the money supply growth. In that case, changes in money growth would reflect exogenous changes in monetary policy, which destabilized the price level.

In this case, the truth is somewhere in between. Inflation rose sharply in 2021 and has fallen off a bit in recent months, but the change in inflation is much smaller than the change in money growth. This means that most of the change in money growth reflects the Fed accommodating a shift in the real demand for money, and a smaller portion reflects an exogenous monetary policy that caused inflation to rise sharply and then fall back somewhat.

Here I’d like to focus on the shift in real money demand, which explains most of the pattern we observe in the graph. Why did the public wish to hold larger real cash balances in 2020 and 2021, and why has the real demand for cash balances fallen off somewhat in recent months?

The answer seems clear. Nominal interest rates plunged from 2.5% to zero during the Covid crisis of March 2020, and nominal interest rates rose sharply during 2022. The fall in nominal interest rates sharply increased the demand for real cash balances (although other factors such as stimulus checks might have also played a role.)

With the recent rise in nominal interest rates, investors are moving from relatively lower-yielding bank accounts to higher-yielding alternatives.

I don’t pay much attention to the monetary aggregates, as I believe the Fed mostly accommodates shifts in money demand. One counterargument is that those who do focus on the monetary aggregates saw the inflation problem before the rest of us.

I would respond as follows. If the Fed had adopted an appropriate monetary policy during 2020 and 2021, the money supply still would have risen extremely rapidly, albeit a bit less rapidly than it actually did. And in 2022 the money supply growth rate might well have fallen more quickly. If that had occurred, those who focus on the money supply growth rate would have warned about an inflation crisis that (by assumption) never occurred.

There are certainly occasions when the money supply gives an accurate read on the stance of monetary policy, or at least the direction of a policy shift. Nonetheless, I find other indicators to be more useful, on average. (But not the Phillips Curve!!)

PS. Keep in mind that while the 30% M4 growth rate did accurately signal an upsurge in inflation, it did not give us any useful information on how high inflation would get.

More By This Author:

A Chat On Supply And Demand(Almost) Nobody Gets Macro

Fiscal Stimulus Is Costly