What Missing Workers?

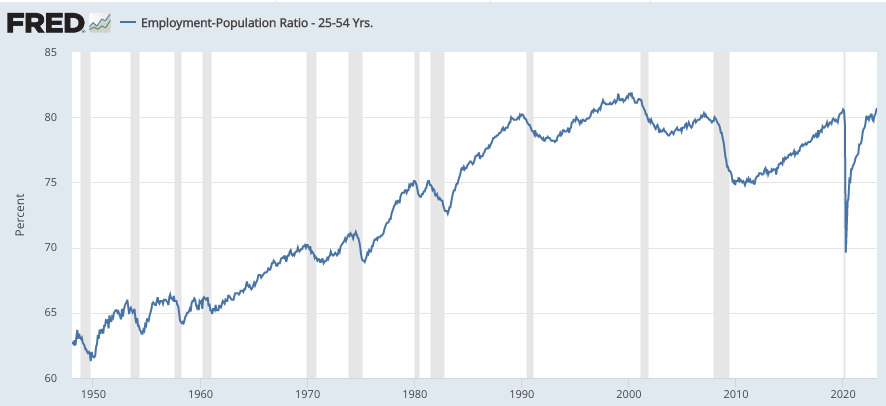

I saw that the prime age employment/population ratio hit 80.7 in March. With the exception of a few years during the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s, that’s the highest employment rate in US history.

(Click on image to enlarge)

So why all the hand-wringing about “missing workers”? You know, the workers that supposedly dropped out due to Long Covid, or an addiction to playing video games, or an addiction to opioids. People keep writing essays about the missing workers, but I can’t see what data they are trying to explain. Can someone help me?

It’s worth noting that the labor market remained absolutely red hot in March, with payroll employment surging by 236,000 (a bit more than expected.) That’s far above the trend rate of employment growth (which is likely less than 100,000/month.) Both Bloomberg:

And the FT:

US jobs growth slowed in March as Federal Reserve tightening bites

missed the big picture. It would be like a Phoenix weather forecasters suggesting that there was a cooling trend when the temperature fell from 113 to 111 degrees.

During 2007, payroll employment growth fell below trend 6 months before the recession began in December. During 2000, employment growth fell below trend 10 months before the recession began in March 2001. If that pattern holds again, then we are likely at least 6 to 10 months away from the onset of recession, as growth is still far above trend. But of course, this pattern may not hold in the next downturn, indeed during earlier business cycles employment growth occasionally declined right before the onset of recession.

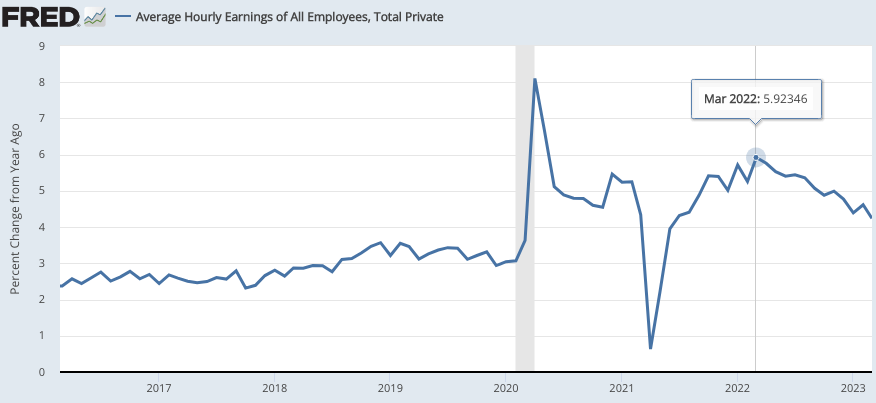

Right now, I’m much more interested in average hourly earnings than I am with the employment figures. I’ve argued all along that price inflation doesn’t matter, rather what matters is NGDP growth and wage inflation. But of course price inflation does matter in one sense; the Fed has a 2% PCE inflation target. So they need to get NGDP growth and wage growth down to a level consistent with a 2% average inflation rate.

If NGDP growth suddenly falls to 3.5% and nominal wages are still growing fast, then you get a recession. (You need 3.5% NGDP growth to account for 2% inflation, 1% productivity and 1/2% labor force growth.) So to create a soft landing you need wage growth of about 3%, so that when NGDP growth slows to 3.5% you can still have full employment.

I’m happy to report that we are making some progress toward that goal. Twelve-month growth in average hourly earnings peaked at 5.9% in March 2022, and has since fallen to 4.2%:

(Click on image to enlarge)

This has been a pleasant surprise. When I was younger, the US labor market was less flexible (perhaps due to more heavily unionized manufacturing jobs.) A labor market this hot would have had faster wage growth. If this downward trend continues, then the unemployment rate in the next recession (which Bloomberg says is certain to occur before October) will be fairly mild. I have my fingers crossed. But I fear that squeezing out that last 1.2% of excess wage growth won’t be as easy.

Some people focus on aggregates like NGDP and total earnings, which are also very important. Here I’d say that slowing the aggregates is essential for controlling inflation and slowing hourly earnings is essential for getting a soft landing when conducting your anti-inflation policy.

On the downside, I expect that RGDP growth will remain weak for many years. Trend RGDP growth is down to about 1.5%, and is likely to remain there until AGI produces a brief surge in growth just prior to human extinction.

More By This Author:

Alternative Approaches To Monetary PolicyFDIC And Small Banks

The Return Of Industrial Policies