What Could Go Wrong? - Saturday, Nov. 11

Exploring federal budget data is a journey through endless rabbit holes, some of which are eerily close to Alice in Wonderland insanity. Countless variables interact in unexpected ways. Seemingly small changes can cascade into billions of dollars within a few years.

Another problem is the “unknown unknowns,” as Don Rumsfeld famously dubbed wartime surprises. We don’t know what we don’t know. No one, including the Congressional Budget Office, can predict everything. These unknown unknowns can have staggering budgetary impacts—COVID-19, for example. Plenty of us were already saying the debt was out of control. Then this tiny virus came along and said, “Hold my beer.”

This should be one of our greatest concerns. Not another pandemic, necessarily, but something we don’t presently anticipate could easily blow another giant hole in the budget. The Treasury has a lot of borrowing power but it’s not infinite.

The CBO knows all this and, in its own wonky and methodical way, tries to inform Congress where the current policies will lead. That depends on a slew of assumptions that can be optimistic, pessimistic, or anywhere in between. Today, we’ll look at some of the CBO’s “alternative scenarios.”

Spending Freeze

I’ve been focusing on debt because I think it is where the rubber is going to meet the road in the various cycles I’ve described. Every potential future we have looked at is going to require compromise and changes. Nowhere will that be more evident than in the coming federal budget and debt crisis.

The way we solve it, this “rationalization” of debt not just in the US, but the entire world, will set the stage for how the world progresses afterwards. If we can't compromise on this issue, other crises could be far worse, or even violent.

For years, when my children and friends asked me how can the United States survive if we don't solve “X” problem, my glib answer has been to say that we will 'muddle through.' And for all my life that has been the correct answer. But because we have repeatedly kicked the can down the road while spending more money and running up ever more debt, we make the possibility of a resolution ever more difficult.

There is a nontrivial chance—globally, not just in the US—that some governments and markets will simply cut ties to others. Not a particularly high probability right now, but in my opinion, higher than it was 20 or even five years ago. We can't even imagine the chaos.

And it is precisely that chaos that makes me optimistic we will actually figure things out. The cost of not doing so will be higher than the cost of compromise. And as we are seeing, the cost of compromise is going to be quite high, both financially and philosophically.

With that said, let's jump back into the CBO alternative possibilities. First, let me clarify some terms. I (and many analysts) tend to use the words “forecast” and “projection” interchangeably. The CBO has a different practice. It makes economic forecasts and budgetary projections. The terms have distinct meanings in their context.

Budgetary outcomes depend on legislative decisions, which the CBO can’t (and shouldn’t) try to predict. The best they can do is assume current policies will continue unchanged. The resulting projection is simply a benchmark against which they measure proposed policy changes. It lets them say, “This new spending proposal will increase the debt by $X billion,” other things being equal, knowing full well they won’t be equal.

The CBO’s economic assumptions, on the other hand, don’t depend on legislation. They are calculated from estimates of population growth, productivity, and so on. These can be wrong (as can all others), but the word “forecast” fits. With those distinctions in mind, I’m going to focus on CBO’s budget and economic numbers separately. The agency forthrightly admits both are uncertain, and it publishes alternative scenarios to show the possible costs.

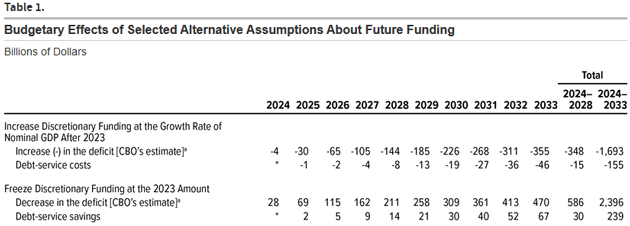

For example, let’s look at a May 2023 CBO report with the thrilling title, "Budgetary Outcomes Under Alternative Assumptions About Spending and Revenues."The law requires the CBO’s budget projections to assume discretionary spending grows at each year’s inflation rate. That’s not what actually happens, but it is what the projections assume.

This alternative report asks what would happen if, instead of growing with inflation, discretionary spending grew with GDP. It also calculates what would happen if discretionary spending were frozen at the 2023 amounts. This is only about discretionary spending, which means defense and most federal agency budgets. It excludes the far larger entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare.

Here are the answers. I’ll explain more below.

Source: CBO

In these tables, a minus sign means a larger deficit for that period. The numbers you see here are not the amount of spending. They are the difference in spending from the baseline projection if these alternative assumptions were applied.

If all discretionary spending programs were allowed to grow at the same rate as the CBO’s nominal GDP assumption, instead of its inflation assumption, the total cost from 2024–2033 would add an additional $1.693 trillion to the debt. This additional debt would incur interest costs of $155 billion over that period, making the total bill $1.848 trillion more than the current projection.

Alternately, if those same discretionary programs were all frozen at their 2023 amounts, the debt would be $2.396 trillion less than currently projected, plus $239 billion in interest savings for net debt reduction of $2.639 trillion (again, as compared to the current baseline).

Are either of those scenarios plausible? Probably not. The discretionary budget, while smaller than the entitlement programs, still covers a vast number of different spending categories. Some of it could be cut, some of it probably needs to grow. Congress is supposed to sort all that out.

In a footnote to that table, the CBO also cautions it doesn’t account for how the alternatives could affect the economy or how potential economic changes could affect the budget. Further, the debt-service costs or savings depend on interest rate assumptions and the assumption that the bond market will always absorb US debt at their projected interest rate costs.

I actually agree that the bond market will always absorb US debt. But at some point in time, the price in terms of interest is going to be a lot higher, I am afraid, than what the CBO forecasts. Just like the bond market wanted higher interest rates to absorb a portion of the 30-year bond offering this week, in the future the bond market might want 50 basis points more for shorter-term debt than the five basis points it asked for this week.

When you start “war gaming” this future, you can quickly come up with scenarios that are quite disturbing. As I have been saying from the beginning of this series, it's going to take a large crisis to solve this large problem. Sadly, we are going to get that crisis. Moving on.

With so many assumptions, we should take these estimates with several grains of salt. A discretionary spending freeze sounds attractive in some ways, but remember, all these programs have constituencies. And a lot of that spending is also the revenue of some large, publicly traded companies, plus the wages of millions of workers. The side effects would be significant, as would the side effects of enlarging the debt with even more spending. That’s why all this is so frustrating; we’ve reached a point where all options are bad.

As I was writing 10+ years ago, we will come to a place where we are faced with very bad choices and even worse choices. The problem is that there will be significant disagreement over which choice is actually utilized. We simply cannot know in advance what those choices will be. We don’t even know who will be making them.

Higher Taxes

Speaking of no good options, a train is coming I think many haven’t considered. Under current law, many provisions of the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act will expire at the end of 2025. That means tax increases—and related economic effects—are already baked into the cake. They will happen unless Congress and the president agree upon a different plan first.

As a reminder, here are some of the popular TCJA provisions that may have reduced your tax bill.

- Tax rates were reduced in most brackets, especially lower income brackets, generally by 2–4 percentage points.

- The standard deduction nearly doubled for most people while personal exemptions were eliminated.

- Allowable deductions for mortgage interest and state/local taxes were greatly reduced.

- Estate and gift tax exemptions were increased.

- Businesses received a “bonus depreciation” benefit for certain kinds of investments.

- And a host of smaller changes.

When TCJA originally passed, the CBO estimated it would both expand deficits and spur economic growth, with the net being an additional $1.891 trillion in debt over 10 years. COVID-19 intervened, so now it’s hard to know if that would have been right. This expiration is already built into the CBO’s baseline projections. It has the effect of reducing the deficit as the CBO assumes the changes will be allowed to expire, and returning to previous policies will increase tax revenue.

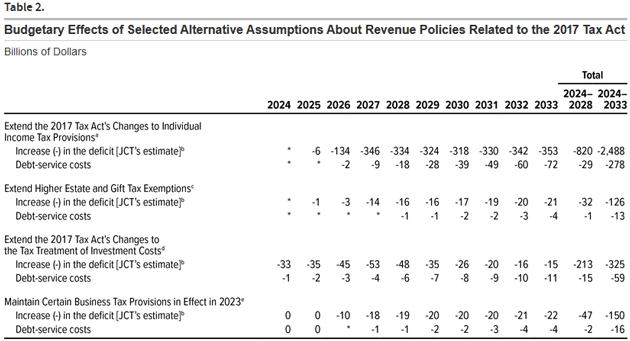

The same May 2023 CBO report linked above considers the effects of TCJA expiration. Here are their findings.

Source: CBO

They break this into four separate assumptions. Here, again, a minus sign indicates that much additional debt would be tacked on to the current baseline projection if Congress extends the TCJA tax benefits beyond their currently scheduled expirations (which mostly take effect in 2026).

Adding the four assumed changes together, they would reduce revenue by $3.089 trillion and add $368 billion in debt service costs over the 2024–2033 period, for a total debt impact of $3.457 trillion. Again, that amount is not presently included in the CBO’s baseline projections, and won’t be unless the law changes.

Will this happen? That’s an entirely political question. Neither party is generally keen on raising taxes, though many Democrats would favor soaking the wealthy. But in this case, the tax increase doesn’t require any further action. It already passed in 2017, when the Congress of that time wrote a law which allowed these provisions to expire. So, it’s going to happen by default, barring new legislation before then.

Realistically, I think Congress will extend at least some of the TCJA provisions no matter which party is in control. Failure to act would be seen as raising taxes, especially on the lower brackets, which is politically toxic. And whatever they do will probably expand the debt, as the CBO estimates. How much will depend on the details.

This is yet another reason the CBO’s projections, or forecasts, or whatever you call them, are best treated as highly optimistic vs. the likely reality. The 10-year baseline currently assumes debt will rise to almost 119% of GDP in 2033. I see no chance it will be that low.

Balking Bond Buyers

Believe it or not, some people believe the federal government can continue indefinitely borrowing as much money as it wants on the grounds “we owe it to ourselves.” An entire school of thought (Modern Monetary Theory or MMT) says we needn’t worry about the debt at all. I understand their arguments, but I think they’re not merely wrong, but idiotic. The current course is not sustainable.

I view this as supply and demand. If the government’s demand for credit rises faster than the available supply of credit, prices (i.e., interest rates) will increase until demand (i.e., government borrowing) shrinks. It’s taking a long time because the government has powers other borrowers lack. But supply and demand will stay in balance. Much of the political discussion is about finding ways to buy more time.

For instance, I have lamented several times recently that Treasury didn’t refinance more of its debt to lock in the very low long-term interest rates of recent years. That wouldn’t have solved the problem, but it would have helped.

Or maybe not. Last week, my good friend Peter Boockvar wrote a long piece explaining why this seemingly good idea never happened. He walked through a bunch of recent history showing how both Steven Mnuchin (Treasury secretary under Trump) and now Janet Yellen seriously looked at issuing more long-term debt. Some small steps happened but not enough to make much difference. What were they thinking?

The Treasury Secretary is responsible for borrowing enough cash to pay the government’s bills but has discretion on how to do so—including what maturity of debt to issue and in what amounts. The law also requires Treasury to get expert advice from the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee.

The TBAC includes representatives of the banks, brokers, asset managers, and hedge funds that comprise the market for Treasury securities. I know people who have been on that committee, and they take their responsibility very seriously. This is not a rubber stamp group by any means.

As Peter Boockvar sees it (along with my other friend Luke Gromen, whom he quotes), the TBAC appears to have told both Mnuchin and Yellen the market simply couldn’t swallow the giant amounts of low-yielding, long-term Treasury debt needed to provide significant savings.

“The point of all of this is to say that while it would have been really nice to lock in low long-term interest rates for the US Treasury, there was a big-time lack of investor demand for long-term bonds and still is the case. My friend Luke Gromen who writes the brilliant weekly The Forest for the Trees highlighted in his Friday piece why this was the case and why it is now, too, ‘The long end of the UST market is far less liquid than advertised, and certainly far less liquid relative to supplies of USTs the US needs to sell given deficits of 8% of GDP in a relatively strong economy.’ Especially so with the Fed and banks selling and foreigners barely buying. Also, while US 'households' have been big buyers, that category includes hedge funds that have been putting on huge basis trades (buying long-term Treasuries and shorting futures).

“When you see the huge damage done to the long end of the US Treasury market over the past two years where TLT (the 20 yr+ maturity Treasury ETF) fell 50% peak to trough, as bad as many stock bear markets, can you just imagine the further carnage on the part of holders if there was even more long-term Treasuries sold.

“Here was Luke's bottom line: ‘The two Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee documents released this week STRONGLY suggest that the explanation for why Mnuchin and Yellen did not term out the US debt is because they could not do so without severe dysfunction in the long end of the UST curve, which as the policy rate of the real US economy, would have touched off even worse banking strains and even bigger Treasury receipt declines than occurred.’

“Here is what TBAC said themselves: UST demand ‘has shifted toward more price sensitive investors over the past two years’ and recently recommended ‘tilting issuance toward tenors less impacted by the rise in term premium and those that benefit from greater liquidity premium.’"

This may seem dry and technical, and it is, but it should also be terrifying. It means the giant pools of money many assume have infinite appetite for Treasury debt are already feeling a little indigestion. They didn’t want to buy long-term debt at low rates in 2020, nor do they want to buy it at high rates in 2023. In other words, they’d rather not buy it at all.

For now, the market still wants shorter-term Treasury bills and notes. How long will that last? No one knows. But not forever.

On the one hand, we have the CBO telling us, as much as the law allows it to, that the government’s borrowing requirements will keep growing with no end in sight. On the other hand, we have the bond market telling the Treasury it should slow down. But the Treasury doesn’t have a brake pedal. Congress and the president do, and there is little reason to think they will even tap the brakes, much less slam them hard enough to stop the debt from growing.

Next week, we’ll look at some other “alternative scenarios” from the CBO, including the effects of limiting Social Security benefits. Quick answer: It would help -- but not without a cost.

At this week’s Republican presidential debate, Nikki Haley was the only major candidate willing to address the Social Security issue head on. The rest punted or went to talking points on other topics. When the supposed party of fiscal restraint doesn’t even want to discuss some minor and obvious tweaks, we are not ready for any serious effort to control the debt.

The “good news” is that we will get there. It just won’t be pretty, and the ride will be very bumpy, full of air pockets and brinkmanship.

More By This Author:

My Affinity For Short-Term Interest RatesDebt Scores

Debt Catharsis