United States: Heading Towards A Real Estate Crisis Worse Than The Subprime Crisis?

In a recent interview on Daniela Cambone-Taub's channel, Mitch Vexler, a real estate developer turned whistleblower, detailed what he considers to be a ticking time bomb at the heart of the US financial system: the way property taxes fuel public school funding and school bonds.

In the United States, a large part of school funding comes from local property taxes. Each school district sets a budget and then adjusts the tax rate to cover it. These revenues are also used to issue school bonds, which finance the construction of school buildings, stadiums, and other amenities. The problem, according to Vexler, is that for several years, property valuations have been artificially inflated, well above actual inflation. As a result, homeowners are paying increasingly heavy taxes, while the “real” value of their homes has not kept pace with this increase.

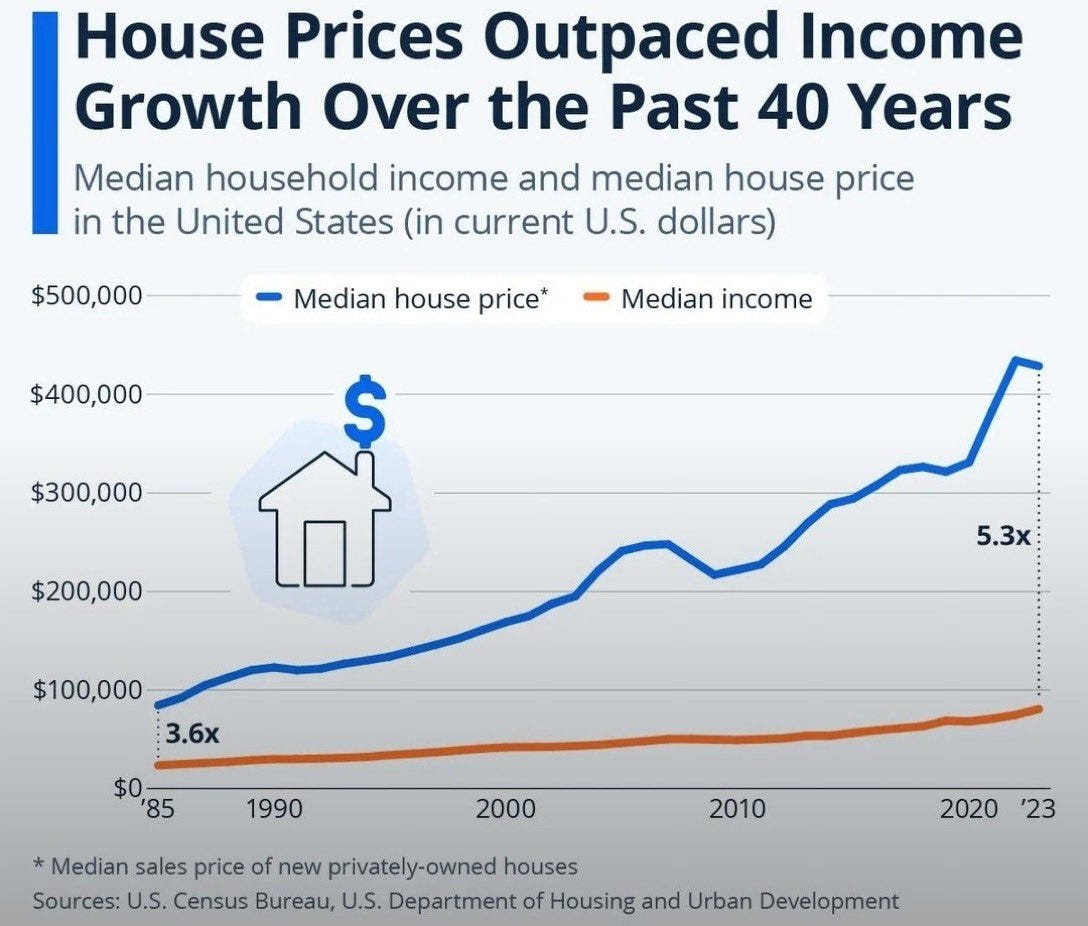

In 1985, a new house cost around 3.6 times the median household income, compared with more than 5.3 times today. This gap reflects a major disconnect between income growth (which has remained virtually stagnant) and house price growth (which has increased more than fourfold).

This increase reflects less a creation of real value than a bubble effect, fueled by decades of artificially low interest rates. Taxpayers thus find themselves taxed on inflated valuations that are completely disconnected from their financial capacity. This mechanism fosters a sense of injustice and reinforces the idea of structural fraud: the tax system captures nominal capital gains that do not correspond to an increase in purchasing power.

However, with demographic trends now unfavorable in most developed countries, this bubble is bound to deflate. When real estate prices fall, local tax revenues will automatically collapse, jeopardizing the financing of school bonds and accentuating the fragility of the municipal bond market.

These excessive taxes have made it possible to issue ever more debt, not to finance new projects, but often to repay old debts. This creates a Ponzi scheme: the system is kept running with ever-increasing debt and taxes, but without ever solving the underlying problem. Vexler estimates that the “fraudulent” or unsustainable portion of this debt now exceeds $5 trillion nationally, a colossal figure that exceeds the scale of many past crises.

Until now, this system has held up because taxpayers have continued to pay their taxes, even while complaining. But we are now seeing a psychological shift: more and more Americans believe that there is no longer any point in paying their property taxes, since they know that the system is doomed to collapse sooner or later. This is where the risk becomes explosive. As in any Ponzi scheme, as long as participants continue to play along, the illusion persists. But if a growing number of households stop paying at the same time, the system immediately implodes. School district revenues plummet, school bonds can no longer be honored, and the chain of trust breaks.

In 2008, the crisis started with unpaid mortgages. When households stopped paying their monthly installments, banks quickly seized their homes and resold the properties, which accelerated the collapse. The current situation is different. The default would not come from loans, but from local taxes. However, the procedures for recovering a house in the event of non-payment of taxes are much longer and more complex: it takes several months, or even several years, before a tax foreclosure is successful. This creates a lag: the crisis would take longer to appear in the figures, but it would erode confidence much more deeply. Above all, the scale is even greater than that of the subprime crisis. School bonds and, more broadly, municipal bonds backed by property taxes represent a colossal outstanding amount, greater than that of the mortgage debt that exploded in 2008. The comparison is striking: in 2008, the crisis started in a segment of the credit market considered fragile – subprime mortgages – whose risks were known but underestimated. This time, the risk is concentrated in a segment perceived as a model of stability.

Municipal bonds are considered to be among the safest assets on the US bond market. They are widely held, not only by specialized funds, but also by pension funds, insurance companies, and a multitude of individual investors. Their appeal is based on two strong arguments: on the one hand, their tax advantages, since they are exempt from federal tax and often from local taxes; on the other hand, the idea that local authorities, supported by the state, will never default, since their revenues are backed by property tax, a regular and binding flow for property owners.

It is precisely this reputation for solidity that makes the current risk so dangerous. Everyone holds them, directly or indirectly. These securities are included in savings portfolios, insurance reserves, pension funds, and even bank balance sheets. They form a kind of bond base, assumed to be stable and predictable, on which a large part of the American financial system rests.

If perceptions were to change and taxpayers refused to continue paying their property taxes, the entire structure would falter. The risk is no longer limited to a peripheral segment of the market, as was the case with subprime mortgages, but directly affects an asset considered central and universally safe. It is this difference in scale and nature that raises fears of a shock far deeper than that of 2008.

If the movement to refuse payment gains momentum, here is what could happen: School districts see their revenues fall and find themselves unable to pay the interest on school bonds. Municipalities lose their reputation as safe assets, triggering massive sell-offs. Banks and pension funds, which hold large amounts of these securities, would suffer considerable losses. Since these bonds are often used as collateral in interbank transactions, their depreciation would cause liquidity to dry up. The most exposed US banks face a crisis of confidence, which could quickly turn into a banking crisis. The Fed is forced to intervene to buy back these securities and inject liquidity, at the risk of triggering a new wave of massive money creation and further undermining confidence in the dollar.

The fundamental difference with 2008 is that this crisis would not originate primarily in the banking system, but rather among citizens themselves. It would stem from the refusal of millions of taxpayers to finance a system they consider fraudulent or unsustainable. This makes it a social, political, and financial crisis all at once. As Vexler points out, there are two possible paths: a “controlled demolition,” i.e., an orderly restructuring with the intervention of monetary authorities, or a “straight demolition,” a sudden and uncontrolled collapse that would plunge the bond and banking markets into chaos far worse than that of 2008.

This latent risk in the US municipal bond market has not come out of nowhere, but rather in a context where the global bond market is already under extreme pressure. Confidence in public debt has been weakened everywhere, and the emergence of a new source of vulnerability in a sector considered risk-free only exacerbates the situation.

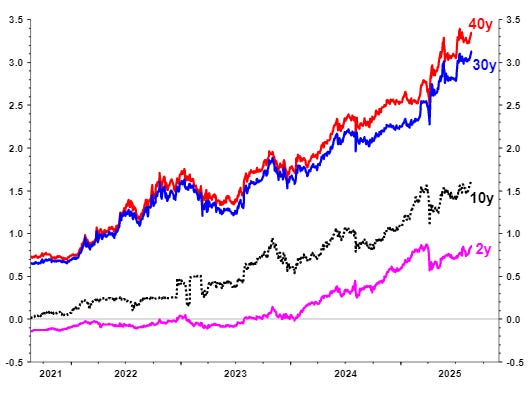

In Japan, yields are hitting record highs across the yield curve, reaching levels not seen in decades.

This surge reflects the decline of a monetary model in which the Bank of Japan, long a pillar of global support through its ultra-negative interest rate policy and massive asset purchases, is no longer able to contain mistrust. For decades, Japan provided markets with an inexhaustible source of cheap liquidity through yen carry trades: investors borrowed in yen at near-zero rates to reallocate this capital to higher-yielding assets, whether US stocks, European bonds, or emerging markets.

However, with the sharp rise in yields across the entire Japanese curve, this mechanism is running out of steam. Japanese 10-year and even 30-year yields are reaching levels not seen in decades, a sign that the BoJ is gradually losing control. If Japanese rates continue to rise, there is a risk of a sharp reversal in carry trade: capital repatriated to Japan to cover foreign exchange losses or secure positions would trigger massive sell-offs on global markets, starting with US and European bonds.

Such a reversal would have a domino effect. Global financing, which has been boosted for years by this artificially maintained rate differential, would suddenly become fragile. Bond spreads would widen, emerging market currencies would plunge, and even Wall Street would see its valuations come under pressure from this liquidity crunch. In other words, what is happening in Japan is not just a local anomaly: it is a crack in one of the discreet pillars of global finance.

In Germany, 30-year government bonds are yielding returns comparable to those seen during the European sovereign debt crisis. The Bund, once an undisputed safe haven, is no longer immune to turmoil, a sign that even the foundations of the eurozone are being called into question.

France, for its part, is seeing its 30-year OATs rise to levels reminiscent of the start of the global financial crisis. For a country at the “heart” of the eurozone, this shift is unprecedented and highly symbolic: it places France on the trajectory of a peripheral issuer, with a risk premium now comparable to that of Italy. The 10-year bond continues its inexorable rise this week.

(Click on image to enlarge)

In the United Kingdom, 30-year Gilts are reaching their highest yields since the 1990s. After the crisis of confidence in 2022, when the market brutally punished fiscal policy, the rise in long-term rates confirms that fragility persists.

Added to all this is a growing divergence between the major central banks. The Fed, the ECB, and the BoJ are no longer aligned. Their monetary policies are following contradictory paths: tightening in the US, hesitation in Europe, and accommodation in Japan. This disconnect is creating an unstable climate that, for some observers, evokes the imbalances of the 1920s on the eve of the Great Depression of 1929.

In such an environment, the emergence of systemic risk on school bonds and, more broadly, on U.S. municipal bonds appears to be yet another piece in an already worrying puzzle. It reinforces the feeling that the pillars of the global bond market are all faltering at the same time.

A shock to US municipal bonds would not remain localized; it would spread to already fragile global markets and activate several channels of contagion.

- The first transmission channel is liquidity. School bonds and, more broadly, municipal bonds are largely held by mutual funds and insurers. A wave of defaults or even a crisis of confidence would trigger massive redemptions in illiquid funds, forcing sales “at market” with significant discounts. Municipal ETFs would start trading at a discount to the value of their portfolios, exacerbating the panic. Insurers and pension funds, which are large holders of municipal bonds, would record losses in value and would have to reduce risk elsewhere, selling Treasuries, MBS, or European debt: this is the snowball effect.

- The second channel is collateral. A sharp drop in municipal bond prices and an increase in repo haircuts reduce the financing capacity of many institutions. In the United States, regional banks—already weakened by unrealized losses on HTM/AFS portfolios – would see their capital and liquidity buffers come under pressure. The SVB experience shows that a valuation shock on securities considered “safe” can trigger deposit withdrawals and forced sales. In Europe, simultaneous pressure on French OATs and Italian BTPs would push clearing houses to raise margins, triggering a chain of margin calls and technical sales, as in the United Kingdom in 2022 with LDIs.

- The third channel is dollar financing. If mistrust of municipal bonds forces US institutions to recapitalize urgently, liquidity premiums (FRA-OIS, cross-currency basis) will widen. Japanese insurers and banks, already facing rising domestic yields, would repatriate capital by selling Treasuries and dollar-denominated European debt, further tightening global long-term rates. With the BoJ, ECB, and Fed pursuing divergent monetary policies, currency arbitrage and portfolio hedging are amplifying exchange rate and interest rate volatility.

A plausible scenario unfolds in several stages. Tax deadlines at the beginning of the year reveal a rise in property tax arrears; school districts record cash deficits and announce payment deferrals on their bonds. Rating agencies downgrade dozens of local issuers; municipal funds experience massive outflows. Municipal spreads soar; the muni/Treasury ratio exceeds its historical averages on a sustained basis; bond insurance monolines see their CDS spreads widen. Regional banks announce heavier-than-expected AFS losses; pressure on their deposits resumes. European markets, already strained by rising French and Italian yields, experience increased margin calls; eurozone banks come under attack on the stock market. The Fed reactivates a Treasury-backed 13(3) facility to temporarily finance municipal bonds (a modernized version of the MLF 2020) and extends liquidity facilities to banks, while the ECB activates a targeted net on OATs/BTPs; the BoJ attempts to stem the rise in JGBs. The relief is real but partial: confidence remains fragile, and the political cost of these support measures is increasing.

The difference with 2008 lies in the point of origin and the scale. In 2008, the crisis started in a risky and well-identified segment (subprime mortgages) and then spread to the investment banking sector. This time, the shock stems from an asset perceived as ultra-safe, distributed among household savings, insurance and pension fund portfolios, and used as collateral. The latency period for tax seizures delays the recognition of losses in the accounts, but it prolongs the phase of mistrust and illiquidity, which is the most destructive. The size of municipal debt and the “cornerstone” status of French/Italian sovereigns in Europe give the contagion a wider reach than in 2008.

A path of “controlled demolition” exists, but it requires swift and coordinated decisions: a temporary freeze on property tax increases and mediation mechanisms for taxpayers in difficulty; targeted audits and restructuring of school bonds (extended maturities, reduced coupons, limited and conditional government guarantees); reactivation of a Fed repurchase facility for municipal bonds to break forced sales; in Europe, explicit activation of conditional sterilized purchases by the ECB to contain French/Italian spreads, while providing liquidity facilities for sovereign repos. The key is to address the cause (local unsustainability and taxpayer confidence crisis) while preventing illiquidity from turning into a banking crisis. Otherwise, the combination of a muni shock, pressure on European sovereigns, and Japanese/Asian reallocation away from long-term debt would create the ingredients for a global systemic bond crisis.

Until markets are certain that authorities are moving towards a form of “controlled demolition,” in other words, a gradual and deliberate restructuring of the school bond system and the most fragile public debts, gold will continue to play a central role as a hedge.

Investors know that bond risk today is different in nature from that of past crises. It is no longer simply a matter of monitoring the ability of a state or district to raise funds, but of assessing the soundness of a structure built on huge outstanding amounts, intertwined with bank balance sheets, pension fund portfolios, and interbank market collateral mechanisms. The complexity is such that breaking points are difficult to identify in advance.

Faced with this growing opacity, physical gold offers a simple and universal answer. Unlike bonds, it is not backed by a taxpayer's ability to pay or a central bank's credibility to intervene. It is free from counterparty risk and does not depend on legal deadlines or political decisions. It is precisely because the bond system has become too vast, too interconnected, and too vulnerable to domino effects that gold is once again attracting massive inflows.

The gold price thus reached a new historic milestone at the beginning of this month, trading above $3,500 per ounce.

(Click on image to enlarge)

This symbolic threshold confirms the acceleration of a fundamental shift: gold is no longer just a safe haven asset in times of economic uncertainty, it is becoming the core asset of a financial system that is losing its bearings.

In this climate of mistrust, until investors see a credible plan for orderly risk management – restructuring of local debt, conditional and transparent support from central banks, clarification of the role of collateral – they will continue to turn to gold as the ultimate guarantee. It is not only a hedge against inflation, but a systemic hedge against the unpredictability of bond markets.

It is this combination – European fragility and American vulnerability – that explains why more and more central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and institutional investors are accumulating physical gold or gold via large ETFs such as GLD. They are no longer seeking only to protect themselves against inflation, but against the systemic risk of global bond market disintegration.

More By This Author:

Gold & Silver In World Currency Units Suggests A Next Leg HigherFrance, The New Weak Link In The Eurozone

Markets Face Major Risk Of Liquidity Dry-Up

Disclosure: GoldBroker.com, all rights reserved.