Time Has A Price

One benefit of human progress is the way we gain “common knowledge” that was once anything but common. We observe basic facts—for example, water boils if placed over a flame—and then build on them.

Boiling water took us to steam engines and then much more. But that path wasn’t always obvious.

We see a similar evolution in finance. Early humans (the Sumerians, the Assyrians, the Babylonians, and eventually the Romans and the Greeks) developed a concept of “property” in which a certain person possesses a particular object.

Then came the idea one could “loan” their property to another, giving up immediate control but retaining ownership, in exchange for some kind of reward. This reward came to be called “interest” and now it’s the foundation of every investment decision.

Ironically, these transactions were originally recorded on clay tablets, which were broken when the loan was repaid. But numerous surviving unbroken tablets recording unpaid loans give us an idea of their loan terms, which often made today’s credit card companies look generous.

This is likely obvious to you. It certainly is to me. Yet it clearly isn’t obvious to everyone, and particularly to some central bankers and their advisors. This leads to many of the problems I discuss in these letters.

Last week I mentioned a forthcoming book by Edward Chancellor, The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest. I’m reading an advance copy and it’s every bit as gripping as any science fiction novel. (Those who know my sci-fi credentials know that’s high praise.) It’s an amazing book. I highly recommend you read it when it is released mid-August.

I’m going to spend two, maybe three letters sharing some of the insights I gleaned from Chancellor’s book. It is truly magisterial in scope.

The Propaganda of Free Credit

Let’s start with a basic question. If you have unused property—cash or anything else—why would you lend it to another party?

The answer is because you derive some benefit from the transaction. That’s the case even if you don’t realize it. Maybe you loan the neighbor your lawnmower. You’re just being neighborly; you expect nothing in return. But you still get the benefit of having friendly neighbors who might help you in the future. Your neighbor gets the benefit of an attractive lawn. Everyone is pleased.

Would you loan your lawnmower to a perfect stranger who might or might not ever return it? Probably not. That’s why “interest” is necessary. People with idle cash have no incentive to risk it without some kind of reward.

Edward Chancellor begins his book explaining how all this actually wasn’t always obvious, at least to some people. Charging interest was long regarded as immoral. They called it “usury,” a term we now take to mean excessive interest rates. Originally it meant any interest at all.

The monotheistic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—all considered usury sinful. Ancient Buddhist texts also condemn usury. So did Plato and Aristotle. Pope Benedict XIV condemned usury in a 1745 encyclical, following the teachings of numerous church councils. The Church of England’s Westminster Larger Catechism taught the same.

Hypocrisy existed within all these religions. Lenders charged interest, sometimes a lot of it, as seen on those clay tablets I mentioned. And in due course, people began to argue that interest per se might not be so bad and could even be good. It was not coincidence this occurred as the Industrial Revolution increased the need for capital investment in machinery and materials.

Chancellor describes an 1849 dialogue between Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Frederic Bastiat, both members of the French National Assembly. Those with a libertarian or Austrian economics background know of Bastiat. He was a fervent free trade advocate who wrote numerous pamphlets, the most famous entitled The Law. (He is just one of my favorite classical economists.)

Proudhon is often called the “father of anarchism” but in today’s terminology was more of a socialist. He famously said, “Property is theft.” Not surprisingly, Proudhon was friends with Karl Marx, though they later fell apart.

Here’s Chancellor on the Bastiat-Proudhon discussion.

“The subject under discussion was the legitimacy of interest. Proudhon took an old-fashioned view. Interest, the anarchist proclaimed, is ‘usury and plunder.’ Usury was an unequal exchange levied by those who, because they didn’t deprive themselves of the capital they lent, had no right to demand a greater sum in return. Interest constitutes a ‘reward for idleness, [and was] the basic cause for inequality, but also of poverty.’ In short, Proudhon continued, adapting his most famous statement, ‘I call interest THEFT.’

“That was not the end of the critique. Proudhon complained that interest compounds debt over time, so that a loan over time would grow to become larger than an orb of gold the size of the Earth. Charging for loans slows the circulation of money, he suggested, causing ‘the stagnation of business, with unemployment in industry, distress in agriculture, and the increasing imminence of universal bankruptcy.’ Interest fuels class antagonism and restricts consumption by raising the price of products. In a capitalist society, said Proudhon, workers can’t afford to acquire the objects they produce with their own hands. ‘Interest is like a double-edged sword,’ concluded Proudhon, ‘it kills, whichever side it hits you with.’”

To be clear, Proudhon was against interest, not lending. He wanted more lending, but via a tax-funded national bank making interest-free loans to workers and peasants—an idea that later developed into what we now call “credit unions.”

Bastiat had a practical objection: Lending without interest would mean no lending at all. Here’s Chancellor again.

“Bastiat was having none of this. Interest wasn’t theft, he maintained, but a fair reward for a mutual exchange of services. The lender provides the use of capital for a period of time, and time has value. Bastiat cites the famous lines from Benjamin Franklin’s Advice to a Young Tradesman (1748): ‘Time is precious. Time is money—Time is the stuff of which life is made.’ It follows that interest is ‘natural, just and legitimate, but also useful and profitable, even to those who pay it.’ Far from depressing output, capital made labour more productive. Far from stoking class antagonism, Bastiat believed that capital benefited everyone, ‘particularly the long-suffering classes.’

“Bastiat foresaw disaster if Proudhon’s plans were put into practice. If lending were not rewarded, there would be no lending. To restrict payments on capital would be to abolish capital. Savings would disappear. Proudhon’s national bank would lend, but if the bank demanded security for its loans working people, lacking security, would be no better off. The abolition of interest would only benefit the wealthy…

“The ‘propaganda of free credit is a calamity for the working classes,’ Bastiat concluded. There would be fewer businesses, while the number of workers would remain the same. Wages would decrease. Capital would flee the country. If the bank lent freely, there would be a deluge of paper money. Order would be lost, and the country would exist perpetually on the edge of an abyss. ‘Free credit is a scientific absurdity, involving antagonism to established interests, class hatred, and barbarity.’”

Read that last paragraph (the bolding is mine) two or three times. Then recognize how “free credit” was, until recently, the official policy of most central banks.

And, as Bastiat predicted, it brought calamity.

Borrowing for Peanuts

Bastiat didn’t simply say interest is necessary. He told Proudhon it is inevitable. Proudhon’s no-interest bank wasn’t going to survive long unless it at least required some kind of security or collateral from borrowers. But in effect, that’s a kind of interest payment. You “pay” by demonstrating repayment ability, something most working people of the time didn’t have. The Proudhon idea would have made credit available only to those who didn’t need it (not that much different from today).

That brings us to another issue: Every loan is different. Financing works only if there is some way to differentiate high-risk loans from lower-risk ones. Interest rates do that very effectively. Lenders are compensated for accepted more uncertainty, while less-qualified borrowers can get capital by paying a higher rate.

Interest rates aren’t simply prices; they are information.

The negotiation process helps borrowers and lenders determine fair terms. If financing costs are too high, it tells the borrower to reconsider if their plan is feasible.

This is what we call “cap rate” or the capitalization rate. You see the term mostly in real estate transactions, but the concept applies to any kind of debt-financed investment property. The formula is annual net operating income (NOI) divided by asset value. So if the property is worth $1 million and you can earn $100,000 in rental income, the cap rate is 10%. That’s pretty good.

Interest rates fit into this because to earn that $100,000, you have to pay interest on your loan. A lower interest rate raises NOI, thereby making the cap rate more attractive. But it also makes marginal properties or companies more attractive – possibly luring people to take too much risk.

But what if you were happy with a 5% return? You might be willing to pay $2 million for that property at a 5% cap rate. Low interest rates send a different signal than higher interest rates. And can change the values of not only real estate but all sorts of investments. That’s why so many private equity investments have been done at increasingly lower cap rates. That’s the signal they were getting from the Federal Reserve and other central banks around the world.

From 2008 until recently the Federal Reserve and other central banks kept interest rates abnormally low. They did this because it is the time-honored central bank playbook. Make borrowing cheap and you can generate the kind of economic activity that spurs consumer spending and creates jobs. The trick is to stop the cheap borrowing before it gets out of hand, which they didn’t do (and still haven’t).

Edward Chancellor calls this post-2008 era “Proudhon’s Dream.” Central banks pushed interest rates to the lowest levels in history and in some cases actually below zero. Credit wasn’t just free; it was better than free. Yet it didn’t have the effect Proudhon expected.

“Bastiat’s claim that free credit would be a disaster for working people was not far off. After the subprime mortgage crisis, banks increased the lending rates charged to less creditworthy individuals and small businesses. Private equity barons and other well-connected figures on Wall Street, on the other hand, were able to borrow for peanuts. During the post-crisis decade, incomes barely grew and low-paying jobs proliferated. The less well-off were forced to borrow at high rates and received negative real returns on their deposits, while wealthy speculators and corporations borrowed cheaply and made out handsomely.”

Think about that last line: “Speculators and corporations borrowed cheaply and made out handsomely.” Good for them individually, but in the aggregate, this wasn’t necessarily positive. And it clearly contributed to wealth and income disparity.

Illusory Power

Last week in my Inflation Reaches Unicorns letter, I described how higher interest rates are raising the price of Uber-like services that had been operating below cost. Remember what I said above: Interest rates are information. They’re part of the cap rate that helps investors decide how to allocate their capital. Artificially low rates generate malinvestment by giving false information. They make difficult things look easy.

This isn’t just about Silicon Valley’s startup companies, either. The same incentives distort decision-making at large, otherwise well-run businesses. They make acquisitions or expansion plans that are feasible only at very low rates. Eventually they have to either sell or refinance, which many are now finding difficult. More will do so.

The result is a “financialized” economy in which a handful of companies dominate large sectors. Instead of offering better prices or quality, they borrow cheaply and simply buy any would-be competitors. And all this is happening because central bankers think they know what interest rates should be.

Then they use this illusory power as a tool, a lever with which to move the entire economy, with all its infinite complexity, in a desired direction. We shouldn’t be surprised they fail. The surprise is that it’s not total disaster every time. The Federal Reserve has a bunch of smart people, but they can’t match the collective wisdom of the markets.

You’ve likely heard the line that compound interest is the Eighth Wonder of the World. It’s really true, and not just from the lender’s perspective. The ability to borrow efficiently helps us finance homes, education, businesses, and all the other things that raise living standards.

Interest makes all that possible. Learning how to harness and use it safely was a revolutionary step in human development, just like discovering fire. Yet now we have people playing with fire by manipulating interest rates. It never ends well, yet they keep trying. Here’s the key quote from Chancellor’s first chapter (emphasis added).

“The most important question addressed in this book is whether a capitalist economy can function properly without market-determined interest. Those, like Proudhon, who argue that interest is fundamentally unjust don’t believe in its necessity. To modern monetary policymakers, interest is viewed primarily as a lever to control the level of consumer prices. From this perspective, there’s no problem in taking interest rates below zero to ward off the evil of deflation. But influencing the level of inflation is just one of several functions of interest, and possibly the least important. The argument of this book is that interest is required to direct the allocation of capital, and that without interest it becomes impossible to value investments.”

Let me go a step further. The Federal Reserve has assumed an unwritten mandate of supporting markets—or at least the market thinks it has. This distorts valuations because zero interest rates convey no information… or worse, they convey wrong information.

We are in the situation we are today precisely because 12 people sitting around a table think that they can determine the right interest rate better than the markets and by doing so can improve the total economy. The Federal Reserve’s original job was to ensure there would be no more crashes like the one in 1907 where the markets and banks had to appeal to JP Morgan to save them. He was barely able to.

We need central banks to be the lenders of last resort in liquidity crises. We don’t need them trying to control markets, especially the stock market. They end up sending signals that are all noise; sound and fury signifying nothing. But the market and businesses all over the world take them as real signals. The Federal Reserve created a situation in which it has to raise rates even as the economy enters a recession.

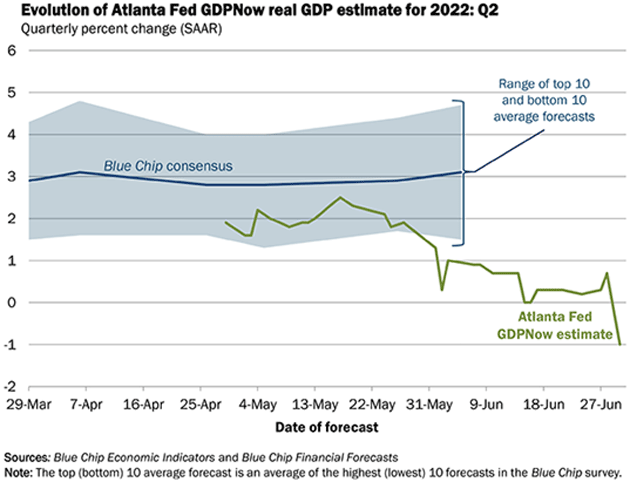

A recession is by conventional definition two quarters in a row of negative GDP. This year’s first quarter gave us one. The Atlanta Fed’s GDP now suggests that the second quarter will be negative, too. I won’t be surprised if the third quarter is also negative and the Fed is still raising rates. But they have to fight inflation as the primary goal, so there are no good choices.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Navigating a Bear Market

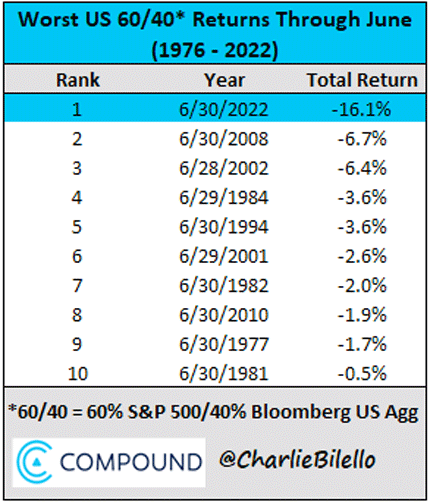

I think it’s safe to say that not just the US but the world is in a bear market. Worse, there’s been nowhere to hide. The traditional answer to moderating portfolio volatility is to create a 60/40 portfolio where the bond part actually gains value in a recession. That hasn’t worked this time. This has been the worst year for a 60/40 portfolio in history by a wide margin because bonds have fallen along with stocks.

Source: Charlie Bilello

We are still in the early innings but there are things you can do to protect and grow your core wealth. You can play an entirely different investment game, one that high-net-worth families and endowments have been playing for decades.

Disclaimer:The Mauldin Economics website, Yield Shark, Thoughts from the Frontline, Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest, Outside the Box, Over My Shoulder, World Money Analyst, Street Freak, Just One ...

more