Three Things – AI, Bonds, And Gold

Image Source: Pixabay

Did you think I stopped thinking about things over this two-week hiatus? Well, you’d be wrong. I am still thinking about lots of stuff, but I will apologize in the meantime for the radio silence. Between the book, our new software, and some coming product launches, I have been busy burning the midnight oil as we gear up for year-end production. I think you’re really going to like what’s coming, so stay tuned. But for now, here are three things I think I am thinking about.

1) How I Am Thinking About the AI "Bubble"

There has been a lot of talk about the AI “bubble” in recent weeks. Some of my favorite stuff came from Derek Thompson and Mike and Ben over on Animal Spirits. Regulars know I am not bearish about AI, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t create some unusual risks. Here’s how I am thinking about it.

Big market booms (and busts) create what I like to think of as a price compression (or depression). When prices boom, that means that many years of future expectations gets priced into the near-term. Multiples are the best way to see this. That is, when expectations increase, you’ll see multiples increase.

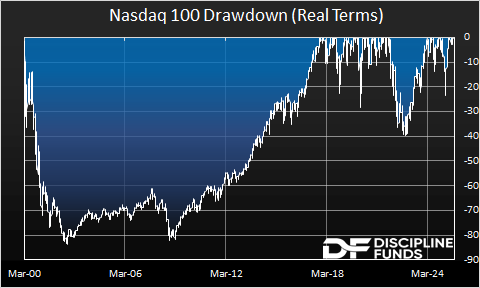

Investors are literally paying more for a dollar of earnings today than they would have in the past. This isn’t necessarily “wrong.” It’s just the present expectation. For instance, in 1999, investors were paying record high multiples for internet-related stocks. This wasn’t “wrong.” In fact, if you’d bought the exact top of the Tech Bubble in 2000, you’d have earned 4.6% per year adjusted for inflation. That’s pretty good for having bought the top. The problem is you would then be tortured for 18 years as you suffered through the price depression as expectations adjusted.

So, here’s the problem with extreme expectations and multiples – it means long-term expectations are high, which creates a lot of downside for short-term disappointment. Now, I don’t think the AI boom is that much like the internet bubble because the AI boom is being driven mainly by the most profitable entities in human existence.

This isn’t a bunch of cute start-ups overleveraging on a new technology that looks interesting. This is the most important firms that exist pouring money into a technology that we know, for a fact, is transformative. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a huge amount of risk in all of this. For instance, we got a snippet of that risk when DeepSeek briefly splashed onto the scene and appeared to have done, with relatively minimal effort, what OpenAI was doing.

This technology is so powerful that we have no idea how it will evolve and who it will nuke in the process. But it’s going to nuke a lot of workers and a lot of firms. Heck, it might end up nuking a lot of the biggest players over time. When Schumpeter wrote about “creative destruction,” he probably never imagined a technology that came close to being as creatively destructive as this can be.

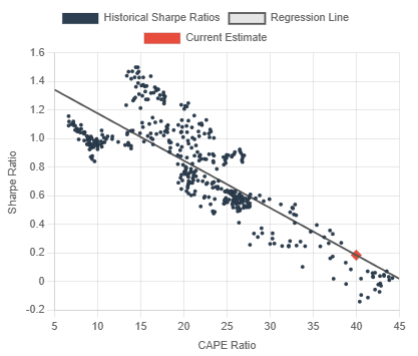

So, when I think of a “price compression,” I mean that you have exacerbated temporal risks. One of the cool things about the Defined Duration model is that we can start to quantify this temporal risk. For instance, here’s the 10-year risk adjusted returns when stocks are at these multiples.

The current multiple in the US is calling for extremely low 10-year risk adjusted returns. This doesn’t necessarily mean the returns will be negative (or even low). But the relationship between 10-year risk adjusted returns and current multiples is very strong. And so that means you might get decent returns from here, but the ride is likely to be much bumpier than usual.

In my Defined Duration model, US stocks have become very long duration instruments on average because of this. Global stocks currently have a defined duration of 21, which is very long relative to the historical average of 17.

When stocks become longer duration instruments, you don’t abandon them. But this could be a very good reason for reducing concentration and owning some things that don’t expose you acutely to the AI boom. And if you have a rather short time horizon, then that could be a very good reason to reduce exposure because those long duration instruments will exacerbate your financial planning risks in the near-term.1

2) TIPS Ladders in ALM Strategies

The Alpha Architect team posted this paper on using a TIPS ladder in an asset-liability matching strategy. William Bernstein discusses this same topic often. I actually wrote an entire chapter in my new book about Bill’s strategy, and we discussed the ways in which he uses a combo of TIPS and T-Bills for different needs.

I really like this approach. Mixing T-Bills and TIPS kind of splits the difference on your goals because you can match the TIPS to longer real return targets, and the T-Bills can be matched perfectly to short-term needs. They play nicely together in an approach like this.

I tend to view bonds as pure principal stabilizers across specific time horizons. So I find it almost antithetical to the instrument to use it to protect for inflation because bonds just aren’t good inflation protectors in the long-run.

This is where I might have a minor point of disagreement with the paper and Bill. I do not like using long-term bonds in an asset-liability matching strategy because I think bonds are terrible long duration instruments. That is, if you have a 30-year time horizon, then I think it would be insane to purposely own 30-year TIPS or T-Bonds in favor of stocks.

I know, I know. People will say stocks aren’t guaranteed to protect you in the long run. And that’s true. But the difference in outcomes and relative risk is gigantic. Over rolling 30-year periods, the stock market will outperform bonds in 98% of outcomes. And it will outperform by 3%-4% per year. Meanwhile in the 2% of cases where it might underperform, we’re talking about relatively small differences. So, if you’ve got a long time horizon, I don’t see the point of matching liabilities to assets like bonds when we know, with a very high probability, that stocks will do better.1

Anyhow, I quibble. This was a very good paper, and I generally like the framework. Heck, I am starting to like any and all asset-liability matching strategies because they’re just so intuitive and match the planning process so cleanly.

3) What is Surging Gold Telling Us?

Gold has been on an absolute heater this year, up 47%. But it’s weird because inflation isn’t raging out of control and there aren’t many signs that worry me at present. CPI and PCE are both bumping around 3%, Truflation is at 2.2%, and our Leading Inflation Index is at 2.7%.

There’s just not a lot of red flags about inflation at present. But that hasn’t stopped lots of people from declaring that the return of big inflation is right around the corner and that gold, being the all knowing asset, is ahead of the curve.

So, why would gold be surging? My guess is that it’s mostly geopolitical risk, and thus institutions and central banks are buying gold in record amounts because there’s a lot of turmoil out there. We have an increasingly isolationist US that is hellbent on crushing the dollar, a messy war in the Middle East, Russia’s never-ending campaign to destroy Ukraine, and China creeping on Taiwan. That’s a lot. Any one of these events create unusual geopolitical risks, so having them all occurring at the same time is quite a lot.

And now the rhetoric on Friday between China and the US doesn’t make me feel better about the potential outcomes, as Trump announced a return to the eye-popping tariffs that worried markets in April. This is not to dismiss potential inflation risks, but I just don’t see it as the dominant driver of gold prices.

So I wouldn’t read too much into the surge in gold as it pertains to inflation. It’s probably got more to do with the hoarding of safe assets due to geopolitical risk than anything else.

Exciting times. I hope you all have a nice weekend and, as always, stay disciplined.

Footnotes

1: This actually got me thinking about a really interesting perspective – are stocks less risky than long-term bonds? Especially in the context of government liability risk? For instance, what would happen to TIPS in a hyperinflation? They’re supposedly inflation protected, but if you had a hyperinflation going on, wouldn’t the inflation-protecting component of the instrument actually exacerbate the inflation that is being protected, thereby creating a sort of positive feedback loop?

I actually don’t know, but I can tell you with near certainty that if I had to pick whether to own stocks or TIPS into a hyperinflation, I would always pick stocks because they’re real assets at the end of the day. You’re just not being properly compensated for the risks, in my opinion.

With long-term bonds (TIPS and nominals), you’re getting a very high level of volatility and interest rate sensitivity, and the best you’re going to do across that time horizon is match inflation, maybe beat it by a little, while assuming you own an instrument that has no credit risk? I think you start getting into murky territory there when we start thinking of government bonds as being “risk free” in the long-run.

More By This Author:

Three Things – Gold, Cuts And DivorcesThe Disruption That Could Crush Inflation

Three Things – Weekend Reading: Sunday, Sept 7

Disclaimer Cipher Research Ltd. is not a licensed broker, broker dealer, market maker, investment banker, investment advisor, analyst, or underwriter and is not affiliated with any. There is no ...

more