Knowns And Unknowns

Image Source: Pexels

Everywhere I go, people ask me what’s next for the economy. My answer depends on what they mean by “next.” Anything can happen next month. I’m much more confident about what we’ll see over the next 5-7-10 years: a painful debt crisis, a “Great Reset” and then a much brighter future as the economy normalizes and new technologies boost productivity and living standards.

The short-term outlook is still important, though, especially if you own a business. You have “can’t-wait” decisions to make about hiring, capital investment, marketing, pricing, and so many other things. You can’t wait for certainty. You have to act on incomplete information and be ready to adapt.

More than I can remember in the past, you have to take any single data point with a grain of salt. We will look at some data today that shows at least part of the economy to be softening. Inflation is still a problem. But we can look at other data that shows that the economy is booming.

This comes down to a point I have been making for some time: we have a two-speed economy (if not three- or four-speed). Consumers in the upper half of the economy have a completely different life experience than those in the lower half. And that creates conflicting data which, of course, makes projections and forecasts more difficult.

Information is even less complete than usual right now due to the government shutdown. Fortunately, we can still look at various private sector data sources. Today I’ll review some of the alternate employment and inflation data to see where we stand. There’s a lot we know and as lot we don’t know… but for the big decisions, we probably know enough.

Gradual Descent

The most recent BLS job report, covering August, showed payrolls grew 22,000 that month and the unemployment rate was 4.3%. The trend at that point seemed to be one of slower but still positive job growth. Now we turn to non-government reports like ADP. They also mostly show a kind of gradual descent.

Source: RSM

ADP’s numbers showed 29,000 private sector jobs lost in September, then a 42,000 gain in October. That is significantly lower than a year or two years ago.

Source: Axios

If ADP is accurate, the labor market is continuing to lose momentum. At the same time, we don’t see evidence of mass unemployment brewing. Layoffs have been increasing, but not enough to change the big picture. It’s more of a static situation, with employers reluctant to hire and workers reluctant to quit.

That doesn’t mean no one is hurting, though. The relatively small number who lose jobs aren’t easily finding new ones. As of August, BLS data showed almost 2 million people had been unemployed for more than six months. I suspect that number is higher now.

Peter Boockvar pointed out this week that ADP’s 42,000 October job losses were highly concentrated in small businesses. Companies with 500+ employees added 73,000 workers. If the net was -42,000, that means smaller companies must have fired 115,000 people. These are the companies least able to manage macro headwinds like tariffs and supply-chain problems. They’re also the least able to compete for top talent.

The question is whether this will get worse. At some point, there won’t be enough job openings to account for population growth and absorb job losses. Then the unemployment rate will rise more.

This next table is from Challenger, Gray & Christmas. It shows the number of layoffs by quarter for the last 18 years. That number has been rising since 2021 and in particular the last two years.

Source: Challenger, Gray & Christmas

The above table does not reflect the latest October number. The negative trend is continuing. Here is their quote, via Mishtalk.

“Through October, employers have announced 1,099,500 job cuts, an increase of 65% from the 664,839 announced in the first ten months of last year. It is up 44% from the 761,358 cuts announced in all of 2024. Year-to-date job cuts are at the highest level since 2020 when 2,304,755 cuts were announced through October.

“Not only did individual companies announce large layoff totals in October, but a higher number of companies announced job cut plans. Challenger tracked nearly 450 individual job cut plans in October, compared to just under 400 in September. March, which had the largest number of job cuts this year primarily due to cuts at the Federal level, saw roughly 350 individual announcements.”

This has only a small macro effect for now, but it certainly doesn’t portend well for the future.

I am going to introduce a few charts from a source that we will want to become more familiar with: Revelio Labs, which combines hundreds of millions of publicly available employment reports into one database. It is part of the alternative unemployment data graph above. You will notice their number is less volatile than BLS or ADP.

Here are a few Revelio charts (all courtesy of Mishtalk). In the first we see that while employment is rising, its growth has flattened.

Source: Mishtalk

Then we can look at the revisions between the first and third releases of BLS data and Revelio. You will notice that the Revelio data is far less volatile. Their initial monthly reports may actually be more accurate than the BLS numbers. We will be paying attention to them in the future.

Source: Mishtalk

Finally, one more employment data point from Revelio. You can see how over the last three years that the growth (change) in employment has been slowing to almost zero, which agrees with the ADP and other private data we are getting.

Source: Mishtalk

Not-So-Great Expectations

The Federal Reserve is trying to address this slowly worsening unemployment with looser monetary policy. In so doing, they are making the grand assumption that looser policy won’t help inflation rise further from its already significant level.

The September CPI report (released only because it was needed to set annual COLA amounts) didn’t show much improvement. The core inflation rate seems stuck near 3%, far above the Fed’s 2% target. I seriously wonder if the FOMC members have simply agreed (or even acquiesced?) to make 3% their new target, without formally adopting it as such. While bad for consumers, this would help ease the debt to GDP number over time. That’s a terrible trade-off in my opinion. In the survey mentioned below, the majority of Americans agree with me that trading high inflation for lower unemployment is bad.

The colors in the bars below separate monthly CPI change into four categories: core goods, core services, food and energy. Each of these can either add to or subtract from the month’s total. Months in which all four rise have been rare recently – but we just had one.

Source: RSM

Since 2022, energy and core goods prices have usually softened the CPI reports. Neither did so in September. They didn’t add much, either, but by simply staying flat they let food and service prices raise the overall CPI figure.

Housing, which is the biggest part of core services, will have even more influence on CPI if this persists. But, as noted, we won’t know this until normal data collection resumes.

My friend Jim Bianco thinks people are underestimating inflation risk. He said this in a recent interview.

“Inflation is one of the worst economic scourges. According to surveys, an overwhelming majority of the public would accept a 1% increase in unemployment to keep inflation down. That’s how serious people are about inflation. So if the Fed misjudges this risk and inflation goes up because they were trying to stimulate the economy, the public is going to find that unacceptable.

“What I’m afraid of is that the Fed could wind up winning that battle and losing the war because inflation expectations become unanchored. In other words, if they ease monetary policy too much, the narrative of a sustained 3% to 4% inflation rate could become deeply rooted in financial markets. This outcome is precisely what the Fed aims to avoid.”

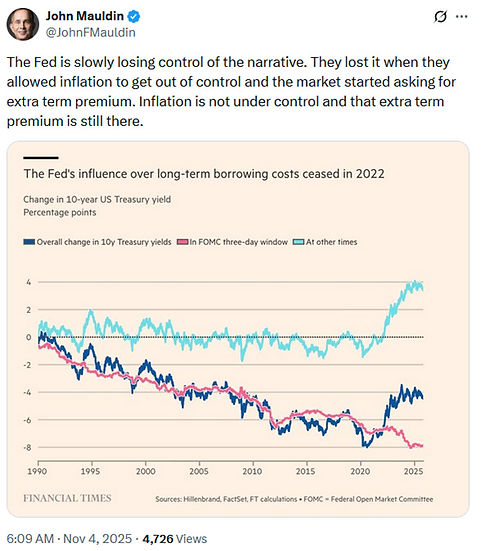

I noted on X (you should follow me) last week that inflation expectations are already starting to become unanchored. You can see it in Treasury yields.

As one reader responded, inflation has been above the Fed’s target for nearly six years now. That followed a similarly long period in which it ran consistently below their target. We seriously need to ask whether the Federal Reserve (or any other central bank) is even capable of controlling inflation. Their once-magical powers seem greatly diminished.

“Anything But”

Some analysts think last week’s FOMC meeting may mark at least a pause, if not the end, of the rate-cutting streak. There were two dissenting votes, one dovish (Miran) and one hawkish (Schmid). We might infer the other voters are happy with the current course, but Powell seemed less sure in his post-meeting comments, saying a December cut is “anything but” a sure thing. The Schmid dissent in favor of holding rates steady was unexpected, which might suggest others are wavering.

(By the way, I have been fairly consistent in calling out liberal economists for their problematic economic views. Similarly, the ideas Fed Governor Steve Miran espouses in promoting his maximum rate cut views are just not grounded in conservative economic thought. I have no idea how he comes to his conclusions, and I am not alone in that view. If we were to adopt Steve Miran’s view, we would see higher inflation and unemployment. We may take that up in a future letter. Economic philosophy is important.)

That’s all reading of tea leaves, of course. We don’t know what the next Federal Reserve move will be. We do know they are now without much of the data they historically depend on, no matter how behind the curve it was. They have less visibility into both inflation and employment – a problem for a self-described “data dependent” committee.

Yet despite all this, GDP growth seems to be accelerating. The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model is at a 4% annual rate for Q3. Even the blue-chip economists are more bullish.

Source: Atlanta Fed

How does this make sense? The answer seems to be “AI.” The torrent of cash going into chips, data centers and all the infrastructure around them is having an effect. It’s not just a tech workers, either. A bunch of electricians, plumbers and air conditioning installers are doing quite well on these projects. Their spending trickles down.

Add that to the “wealth effect” felt by stockholders and there’s enough spending to keep corporate earnings, and the economy generally, in a steep ascent. It would be even steeper without the negative effects of the tariffs and associated uncertainties.

This is all wonderful, but it creates a vulnerability, too. The economy is basically “all in” on AI-driven growth. It may work out well, too, but any crack in that narrative could lead to a rapid unwinding. Some estimates show GDP growth is running close to zero if you back out the AI spending.

Trigger warning: some of the reports I will present below suggest problems in the AI world. And there could be. But I want to emphasize that I clearly understand that all of the big AI companies are spending this money because the demand for cloud, AI and other processing data is simply booming. These companies are building data centers and so forth because the demand is there. The companies are betting that the demand is going to not only continue but increase. And I think they are right. The question for AI investors is to figure out who will be the primary beneficiaries? I suspect that even nosebleed valuations will probably be justified for them. The others? Not so much. With that let’s return to our narrative.

Tech giants are spending vast amounts of cash on AI chips, data centers and related capital investments. So far, most of the expense is coming out of their operating cash flow. This chart shows both amounts for five of the big players: Google, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft and Oracle.

Source: Timothy B. Lee

These companies were already generating giant amounts of cash before the AI boom took off in 2022. This has let them spend freely on AI without needing to borrow. But the gap is starting to narrow, so it may not work that way much longer. Then what?

The yearly bars below show annual bond issuance by AI big tech firms. They often borrow money even when they don’t strictly “need” to because they can get very low rates. That may be why their bond issuance dipped in 2023 and 2024. But now it’s zooming higher again – much higher.

Source: Conor Sen

September and October of this year saw a huge explosion in AI-related borrowing, much of it in one huge Oracle deal. If this continues, it will mark a new stage in the AI boom – one that includes a channel for problems within those companies to affect the broader financial system.

Being in a position where your costs are rising faster than your income is uncomfortable for any family, and for big companies, too. Reading the Microsoft earnings report, you find that Microsoft actually says that earnings may be constrained because they don’t have enough capacity to service the demand. You can find analysts who think Mag-7 earnings will fall, but in general the optimism seems to outweigh the negatives.

All that said, Jim Bianco sees similarities to the internet boom. This is from the same interview I quoted above.

“If you look at the individual AI companies, most of them are fully valued. They are not cheap by any stretch of imagination, but they’re not at ridiculous valuations, other than a few standouts such as Palantir. But here’s the problem: every AI company is priced as if it’s going to win, which is reminiscent of the dotcom bubble in the late 1990s. Back then, every internet company was priced as if it was going to win. If you stuck .com on the end of your company’s name, its stock price doubled the next day – and that’s when we had the big correction. So yes, the internet was important. It mattered, and there were huge winners, but not everybody won.

“… That’s what I’m seeing with AI: we’ve priced everybody to win. The issue is everybody looks at their deal to build a data center. They present their project, including power usage etc., to a private credit firm like a Blue Owl or Apollo. On paper, it all makes sense, the economics work. But the problem is there are dozens of other people making the exact same decision, all at the same time, and collectively this leads to a massive overbuilding. Excesses like these are a recurring theme throughout history, from the major railway bubble 150 years ago to the fiber-optic build-out during the dot-com mania. Every time, so much infrastructure was constructed that a portion of it was never even utilized.

“If you overlay the dotcom bubble, there were two waves. First, you had the build-out wave, the infrastructure wave. That was highlighted by Cisco, JDS Uniphase and similar names becoming the most valuable companies in the world, leading into the 2000 peak. Then, we had a big stiff correction which left us with a functioning internet because we built it out much faster than we would have otherwise. That paved the way for the second, bigger and more durable wave…. the rise of content companies such as Facebook and Google, and eventually Uber and Airbnb.

“In AI, we’re still in the infrastructure wave, headed by Nvidia. So, if we have another stiff, steep correction, we’ll ponder the implications of the AI capabilities we’ve inherited from this period of overbuilding. But the problem for investors is simply that the company founder who will achieve the big commercial breakthrough with AI is still going to school with other twelve- to thirteen-year-olds today… the future AI winners don’t exist yet, they’re to come.”

The problem now, assuming AI follows something like the dot-com pattern, is that the correction period between the infrastructure overbuilding phase and a more durable second wave will be much worse than the early 2000s. We are simply not prepared – socially, politically, or economically – for that kind of pain.

As always, timing is the hardest part to predict. I can imagine staying in something like the current balance through 2026 and maybe beyond. I don’t see it lasting until 2030. Long before then, the out-of-control federal debt will be forcing major changes on the economy.

Final thought: the Federal Reserve is a no-win situation. Inflation is high. Unemployment has the potential to rise soon. I don’t know what the Fed will do but they will look bad no matter what.

More By This Author:

Debt Cycles, Eastern Style

The Final Crisis: This Is Our Future

Big Debt Cycles