Janet’s Got A Squeezebox, Kuroda Can’t Sleep At Night

This week, markets eagerly await the FOMC rate decision, due out on Wednesday September 21st. The consensus view is that the Fed will leave the Fed Funds Rate unchanged, for now. However, comments made by several officials, during the past two weeks appear to indicate much disagreement at the Fed. I will leave whether the dissension is real, or orchestrated to test markets’ reaction, to the reader, but I would point out that the Fed rarely tightens unless it believes the markets are prepared. Based on market reaction to hawkish Fed commentary, notably that of Fed vice chair, Stanley Fischer, market participants (many of whom have loudly proclaimed their bullishness for fundamental reasons) do not wish the Fed to raise the range of the Fed Funds Rate 25 basis points to 0.50% to 0.75%. If markets are truly fairly valued for a strong and/or improving economy, why are markets so skittish about a September Fed Funds Rate hike? It is probably because asset valuations (all asset valuations) have been influenced by Fed and foreign central bank policies.

Market participants have been very selective when declaring asset classes as propped-up or made rich by Fed/central bank policy. They tend point to any and every asset class but the one in which they are active. The truth is; no asset class has been beyond the influence of Fed/central bank policy. This is because all asset classes are, to some extent, linked. In the fixed income markets, it happened something like this:

- Fed buys U.S. Treasuries and GSE debt

- UST and GSE investors were pushed into high- quality investment grade corporate and municipal debt

- High quality corporate and municipal investors were pushed into BBB credits and dividend stocks

- BBB-rated bond investors were pushed into BB-rated high yield credits and dividend stocks.

- BB-rated bond investors were pushed down to B-rates bonds

- B-rated bond investors were pushed down into CCC-rated and lower bonds

Along the way, not every investor in respective asset classes moved down in quality (farther out on the risk curve). Thus you get a crowding effect in each asset class. This works like an accordion. The Fed pushes down the yields in Treasuries and agencies, this pushes down yields in adjacent asset classes on the risk spectrum. One by one, each asset class experiences upward price pressures, lower yields and credit spread compression. As with an accordion, movement is greater as you move away from the base (in this case, UST).

When (and if) the Fed (and other central banks) reduce or relinquish pressure on sovereign and agency debt yields, the trend is reversed. As yields of U.S. Treasuries and Agency debt rise, investors who were squeezed out and sent to riskier asset classes, return. Thus, after a modest to moderate rise in yields, natural investor demand could halt and/or reverse the rise of long-term interest rates, stemming from reduced asset purchases by central banks. Unless inflation pressures surge, investors should replace central banks, if and when central banks reduce or cease asset purchases. The result is that, without a surge in inflation, fears of a bubble in sovereign debt are probably overdone. Again, this does not mean that prices of long-dated sovereign debt cannot fall (bond prices fall as yield/interest rates rise), but without centrals banks participating in that market, room is made available for traditional sovereign and agency debt investors.

As the Fed (and other central banks) reduce their presence in sovereign debt, the flow back in on the risk spectrum should pick up speed. The move back in on the risk curve is like a snowball rolling downhill, the further in on the curve, the greater the demand from investors and the better supported bond prices should be. This could leave lower-rated asset classes with little support.

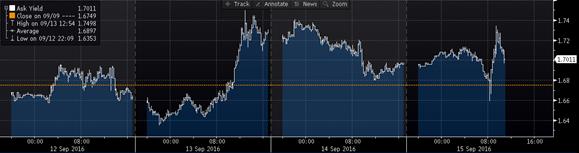

We saw some of this last week, as the yield of the 10-year UST note twice approached 1.75%, on an intraday basis, buyers returned. This drove the 10-year UST yield back below 1.70%.

10-year UST note traded yields 9/12/16 through 9/15/16 (Bloomberg):

I thought that once the 10-year UST note yield broke 1.70%, we could see a run to the 2.00% area, mainly on investor panic. However, it appears that 1.75% was sufficient to attractive demand, even in the midst of somewhat sloppy 10-year and 30-year UST auctions.

This also happened when the Fed announced it planned to taper asset purchases in 2013. The bond market threw a tantrum, pushing the 10-year UST note to 3.00%. However, once at 3.00%, investors rushed in to fill the demand void left by the Fed. Long-term UST yields have trended lower since.

10-year UST Yield since December 2013 (Bloomberg):

The Name of the Dance is the Reverse Twist

Unlike during past interest rate cycles, central banks have actively influenced long-term rates, this time. Thus, when it appears as though central bank sovereign debt buying might not be as strong as markets anticipated, long-term bond yields can rise. Wait you say, the Fed has only reinvested the proceeds of its portfolio and is not poised to change its asset purchase program. The majority of recent upward pressure on long-term UST yields seen last two weeks did not come from the Fed, but from the ECB and BOJ.

At their most recent respective meetings, the Bank of Japan and European Central Bank surprised market by neither increasing QE asset purchases nor hinting at more in the near future. This caused the yields of the 10-year German bund (DBR) and the 10-year Japanese government bond (JGB) to rise. As there are a plethora of currency and interest rate arbitrage and carry trades in the markets today, a rise in long JGB and DBR yields tends to push long-dated UST yields higher as well.

Last week, the chatter on the Street was that Japan might do a reverse twist. This is where the bank of Japan would reduce long-term bond holdings and lower short-term rates farther into negative territory, steepening the yield curve and thereby making lending more attractive for banks. This is all well and good, but there are challenges and pitfalls to this idea.

Challenge I: Steepening the yield curve may make lending more attractive for banks, but it does nothing to generate demand for credit. In fact, it could discourage borrowing by raising borrowing rates which use long-term interest rates as benchmarks, such as mortgage rates. Rising long-term rates, which drove mortgage rates higher, after QE1 and QE2, in the U.S. (both of which involved buying only short-term bonds) is why the Fed launched the famous “twist” program in the summer of 2011 and outright long-term asset purchases in September 2012. The bank of Japan would likely reduce demand for credit by doing a reverse twist.

Challenge II: Japan’s population is old and is getting older by the day. As people age, they become less likely to demand credit, particularly mortgage credit. Increasing the supply of credit in an economy with rapidly aging demographics might be akin to increasing the supply of children’s tricycles. The trikes may become plentiful, but who is going to buy them?

Pitfall: By allowing long-term rates to rise, Japan could attract capital. This is exacerbated by conditions in currency markets which have made it very expensive (too expensive) for Japanese investors to hedge currency and purchase foreign sovereign debt, such as U.S. Treasuries. If money moves back into JGBs, the yen could remain well-supported or strengthen further. This would likely hold down or push lower inflation in the Japanese economy. This is precisely what the Japanese government does not want.

It is the concern that the BOJ will loosen its grip on long-term rates that sparked the move higher in long-term sovereign debt yields around the world.

I have been in the fixed income markets for more than 25 years. During that time I never cease to be amazed by the myopia that pervades market participants. There is the idea that, if Japanese investors reduce their holdings of long-dated U.S. Treasuries, the removal of said demand would reduce the overall number of participants in long-dated U.S. Treasuries. Not only is this a foolish assumption, it is an assumption which has been proved wrong throughout history and in a number of markets.

What myopic market participants and strategists seem not to acknowledge is the existence of the squeezing-out or crowding-out effect. When new participants enter a market and push down yields and/or push up prices, many traditional buyers are squeezed or crowded-out of that market. They seek opportunities in other assets (see the lead section of this report). When the new participants leave the market and prices fall and yields rise, traditional buyers usually return, thereby limiting or, in some cases, reversing the selloff. When Treasury yields rise it tends to draw capital from riskier asset classes. Thus, UST prices/yields could be well-supported while high-risk assets could become a veritable ghost town, leaving those late to exit to suffer losses and, in junk debt, credit defaults.

The idea that traditional buyers are immobile and do not react to new participants in a market by seeking better opportunities when valuations become unattractive borders on stupidity. After all, what is portfolio reallocation all about? When valuations in a sector or asset class become richly-valued, investors and portfolio managers seek other (hopefully better) opportunities. This occurs in sovereign debt markets as well. The fact that the UST 10-year note experienced strong demand as its yield approached 1.75%, last week (from what appears to be pensions and insurance companies) appears to bear this out.

There is another possible course of action the BOJ could take. To prevent the yen from rising as it does a reverse twist, the BOJ could simultaneously purchase U.S. Treasuries. A central bank trying to stimulate its economy and boost inflation by buying its own government debt, corporate debt and common equity probably does not care very much about the cost of exchanging JPY for USD. By purchasing more UST notes and bonds, the BOJ could keep the USD strong versus the JPY and hold down long-term U.S. interest rates (a consequence of said policy rather than a goal).

As you can see, there are many moving parts to central bank participation in capital markets. It is not as simple as; central banks enter a market and increase demand/central banks leave a market and reduce demand. Although this is partially true, we must be conscience of the fact that central bank entrance into and exit from markets can (and usually does) cause some traditional buyers to leave and return to said markets.

Fed concerns did add to the selling pressure on the long end of the curve. As disappointing economic data poured in, long-term UST yields moved higher. This confounded investors, advisors and some in the financial media as disappointing economic data should correspond to a more dovish and patient Fed. Although it may seem counterintuitive, by pushing long-term rates higher, the bond market is expressing agreement with the idea that the Fed will exhibit patience at the September FOMC meeting. An accommodative Fed is seen as inflationary, or at least not anti-inflationary.

As I stated earlier in this report, there seems to be significant support for the 10-year UST note around the 1.75% area. Although there could be a moderate overshoot, if retail investors panic and flee the long end, I would expect buyers to rush in and scoop up long-dated bonds at relatively higher yields.

Let’s be clear. It was the absence of increased bond buying and the lack of jawboning of more bond buying by the BOJ and ECB, that sent long-term rates higher, around the world. Long rates did not rise because of an improved economic growth environment or growth-generated inflation pressures. Long interest rates/sovereign debt yields climbed because market participants feared that central banks may lose their grip on the long end of respective sovereign yield curves. That the 10-year UST note found support around the 1.75% area, the 10-year JGB found support around 0.00% and the 10-year German bund found support around the 0.07% area indicates to me that the markets are not all that concerned about rising inflation pressures, from improved growth or otherwise.

We must also remember that sovereign debt yields remain considerably below levels seen a year ago. Even if long-dated sovereign debt yields returned to autumn 2015 conditions, they would still be considered historically low.

10-year UST, JGB and DBR YoY (Bloomberg):

.jpg)

I would welcome central banks losing grip on the long end of the curve as it would allow me, where in the best interest of investors, do deploy cash and/or rotate some short-term capital somewhat further out on the yield curve. However, I will not delude myself into thinking that a 3.00% or even a 2.50% 10-year UST note is months away. With global inflation low and extreme policy accommodation fast becoming the neutral policy (in real terms) in Europe and Japan, along with very close correlations among long-term sovereign debt yields, I don’t see long-term interest rates rising very much during the next year, or years. In my opinion, tighter Fed policy will only succeed in flattening the yield curve and limiting the potential rise of long-term interest rates.

Disclaimer: The Bond Squad has over two decades of experience uncovering relative values in the fixed income markets. Let ...

more

I believe the Fed sets the table for low yields, but even after QE, yields continued to go down. Yields went down as there was prosperity in the 1990's. In good and bad times bond yields go down over time. I think demand for bonds is growing, which the Fed certainly engineered, as no one wants another AIG. The demand for bonds as collateral continues to grow. But it is supply and demand.

Actually, long UST yields crept higher after QE1 and QE2. The first two iterations of the Fed's QE bond buying focused on buying securities with maturities two years and in. This was similar to lowering the Fed Funds Rate. Accordingly, the yield curve steepened with short yields falling and long yields rising (anticipating inflation from increased bank lending from the bull steepening yield curve). Markets did not anticipate the effects of financial regs which curtail bank lending and demographics which reduces the need for credit.

After lending did not increase from a steep curve (banks were not going to be able to extend home mortgage credit to anyone without pristine credit profile), the Fed started twisting in the summer of 2011. The goal was to drive down mortgage benchmarks, thereby lowering mortgage rates in the hope of luring well-qualified borrowers off the sidelines. This worked, to some degree, as mortgages for home purchases and refinancing are up among upper-tier borrowers.

The problem is that many people believe that it is only a matter of time before the old normal returns. In reality, each economic era is different. We never "go back." Notice I said "era" and not cycle. We are in a new economic era not simply a new economic cycle.

thanks for sharing