Industrial Size Surplus

Modern economies, even small ones, are unfathomably complex. The number of variables is far more than any human can comprehend or any model can track. It’s really no wonder so many forecasts are wrong.

In my 2024 forecast letter, I predicted “A Muddle-Through Year.” That’s still what I expect -- but not for everyone, nor for every corner of the economy. Some people are going to have problems. Today’s letter will focus on one sector I think will face problems: commercial real estate. CRE may have a harder time than many others in this Muddle-Through world.

We knew when the Fed started raising rates almost two years ago (I know, time flies) that highly leveraged industries would be hit the worst. Few are more leveraged than the owners of large commercial properties. They take on giant debt to build properties and hope the income covers it. Higher financing costs can raise the breakeven point quickly.

A dinner companion last night noted that one of the hotels in his portfolio had gone from an interest rate of 4.8% to 9.2% while other ordinary expenses have also climbed with inflation. Even higher room rates haven’t made the hotel profitable. Multiply that by many thousands of commercial buildings around the country, each with its own particular dynamics.

But that’s not all. The real estate market has changed considerably since 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic has reshaped how and where businesses operate. Demand is evolving faster than supply can respond. That means disruption.

CRE disruption has broader effects, too. Having the right facilities in the right place for the right price is a key constraint for all kinds of businesses. If it keeps you from expanding, then people don’t get hired and customers may face higher prices. This matters to the economy.

As you can see, this is a giant subject. I’m certainly not an expert, but I know some. Today, we’ll see what they are saying. Then we’ll see how it connects to the inflation forecast in an important way you may not have noticed.

Stagnating Desk Demand

Economies are always evolving. This evolution has sped up considerably since 2020 due to COVID-19 and related events. Changes that might otherwise have taken decades unfolded before our eyes.

In some cases, these changes were already underway. Working from home was still a nascent prospect, discouraged by most employers. I had been doing it for years before the pandemic, as had most of our team. This had nothing to do with health; we just found it much easier to attract the best talent when they could live wherever they liked.

When the pandemic forced this arrangement on every company, millions of workers decided they liked it. More important for our topic today, millions of employers saw the potential to greatly reduce their office footprint and expenses. Not all, by any means; some organizations see an advantage in having everyone routinely in the same place. Some are trying hybrid arrangements where people are in the office three days a week or whatever. Companies will experiment and find what works for them.

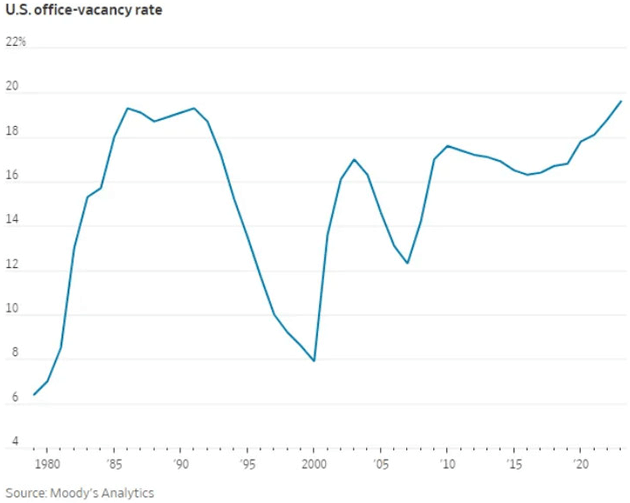

The bottom line, though, is that demand for office space is still stagnating, if not shrinking, leaving many landlords holding excess space that isn’t generating sufficient income. This is slowly but surely getting worse as leases expire and companies close or consolidate offices. Look at this chart:

Source: CRE Daily

Notice that 1980's vacancy surge. That was the result of excess supply rather than reduced demand. I remember in Texas we had “see-through” skyscrapers and unfinished buildings where construction simply stopped. Today’s 19.6% vacancy rate is about the same. And, as noted, it’s still rising as leases expire.

That said, there’s a great deal of variation between cities and even within cities based on each building’s age and amenities. Top-tier “Class A” space in NYC is a hot commodity with (to me, at least) nosebleed rents. Small, older office buildings, not so much.

We thus have a situation where the supply of office space companies actually want to lease is quite limited at the same time landlords have loads of other space no one wants. This pushes average prices down as owners seek to liquidate their unattractive properties. The result: a severe bear market, unfolding out of sight.

Here’s part of a recent MSCI note (CPPI = Commercial Property Price Index and CBD is Central Business District):

“The RCA CPPI for CBD office assets peaked at a record-high level in the first quarter of 2022 and prices have fallen a cumulative 40% since then. The RCA CPPI is an index not tied to any particular price level, but if we peg the index level for the first quarter of 2022 to the simple average of $408 per square foot for all buildings sold in that period, it implies that these same assets would have sold for $245 PSF in the fourth quarter of 2023.

“But not all assets would be able to close at that $245 PSF price level. The MSCI Price Expectations Gap for CBD offices stood at -19.7% for the fourth quarter of 2023. That percentage means that there was a -19.7% gap between the expectations of asset values for buyers and sellers. If buyers and sellers meet halfway on that gap, it implies a market clearing price of $221 PSF.

“So where are prices for that average CBD office asset that sold for $408 PSF in the first quarter of 2022? Realistically, the price is somewhere between $245 and $221 PSF. The buyer of that CBD office asset in the first quarter of 2022 would realize a loss of somewhere between 40% and 46%, then, if they went to market in the fourth quarter.”

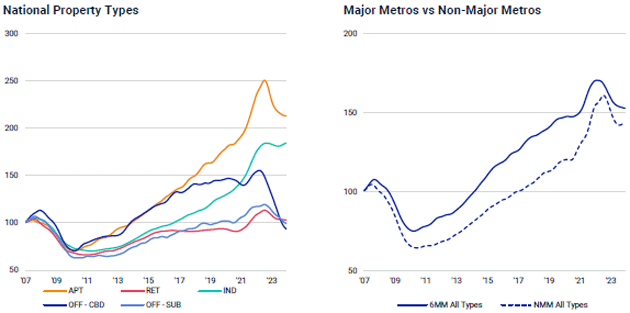

A 40% price decline in a highly leveraged asset class is a big deal, and not just for the borrower. This is troubling for lenders, too. Nor is it just the office category. The left chart below, also from MSCI, shows their price indexes for different property types. You can see how apartment prices fell hard since 2022 right along with CBD office properties.

Source: MSCI

The only commercial property type to have gained much value since 2020 is the “industrial” category. That, I think, is significant and deserves some further exploration.

Additive Change

The “industrial” part of commercial real estate covers a lot of territory, but having it in the lead is a little surprising. After all, this century’s big narrative is that the US is becoming a service-dominated economy.

Under globalization, we outsourced much of our manufacturing and industrial activity to China and others. If the US economy is going to specialize in office-type work, we would expect to see those properties gaining the most value, along with relative weakness in industrial facilities. That’s not happening. Why not?

One clue is in the chart. Notice how industrial property values started growing faster than CBD offices a few years before the pandemic. Some of us were talking in the mid-teens about globalization slowing or even reversing. Trump’s anti-China talk and then tariffs intensified it. So that’s one possible factor.

Then the pandemic severely disrupted global shipping and supply chains. This encouraged US business leaders who had previously embraced just-in-time outsourcing to hold more inventory locally and boost their domestic production capacity. American consumers also shifted more spending to e-commerce, which required additional infrastructure (warehouses, shipping facilities, etc.).

And on top of that, in 2021-2022, Congress passed large stimulus spending bills intended to subsidize US manufacturing, especially microchips and clean energy. They had an effect (and an effect on the debt, too, but that’s another topic).

Add all these together, and it’s a pretty major change. I wouldn’t call it a directional change; the US service sector isn’t going away and will surely keep growing. It’s more of an additive change. We’re keeping what we had and reindustrializing, too.

There are very good reasons for this. From a national security perspective, staying so dependent on Chinese manufacturers isn’t great. That’s one of the few things Trump and Biden agree on and is probably why Biden has kept most of the tariffs Trump imposed. That probably won’t change no matter how our election turns out (despite the fact that they agree, these tariffs are a bad idea with significant costs to American consumers).

If a significant part of the industrial activity we spent the last two decades sending offshore is coming back (what some call “reshoring”), it has some major real estate implications. We will need not just more manufacturing plants but all the supporting logistics: roads, materials, fuel, electricity, vehicles, machinery, and more. And all of those additional inputs will require even more energy. None of this grows on trees. All of it will require land in suitable locations and construction of suitable facilities.

If that sounds kind of old school, remember that AI will be a big part of it. If you use ChatGPT or one of the others, the part you see is only the user interface. You don’t see what is behind it: vast data centers filled with power-hungry processors that need power, air conditioning, wiring, data connections, and people to keep it all humming.

AI infrastructure is going to be a giant industry in itself. That’s why smart players like Blackstone are making big AI real estate investments. It will be a classic “picks & shovels” play. You don’t have to pan for gold yourself to get rich in a gold rush; just figure out what the miners need and sell it to them.

But that’s not all. There’s also money in what the gold rush leaves behind.

Excess Meets Scarcity

We learned this week the Federal Reserve wants to have “greater confidence” inflation is moving toward its 2% target before cutting interest rates. That’s no great surprise, but raises another question. What stands in the way? What keeps the FOMC members from being more confident?

First, remember what the target is. They look at the core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index, which is similar to the Consumer Price Index but with some important differences. The “core” part means it ignores food and energy prices. Most other goods prices have been softening. That leaves services—the largest part of which is housing.

It appears to me the Fed officials are really saying they want to see more evidence housing prices are falling, or at least stabilizing, before they loosen rates. That’s strange when you consider their higher rates are one reason housing is so expensive.

We need more supply to bring prices down, but new construction requires financing, which the Fed has made more expensive. It’s not intuitive to say rate cuts would help reduce inflation. But for housing price inflation, it’s partly true.

The problem with this is that interest rates are a blunt-force tool. The Fed doesn’t have many ways to specifically target housing inflation. The one they’ve tried (buying mortgage-backed securities as part of QE) had a limited benefit and some troubling side effects. Similarly, across-the-board rates cuts might stimulate some housing construction while also stimulating less desirable spending.

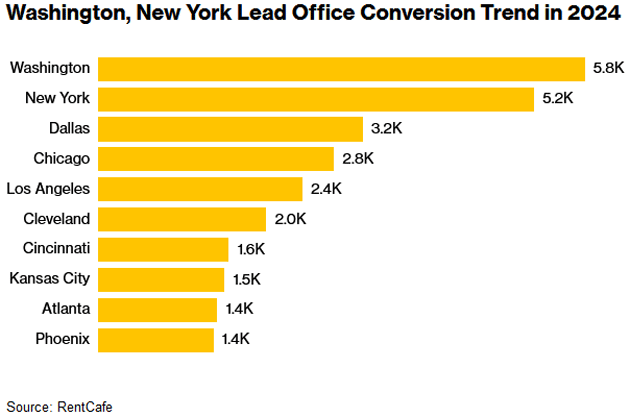

But as always, market forces will find ways to supply our needs. Presently, the US (in total, with many exceptions) has cheap, excess office space and scarce, expensive housing. These may add up to an opportunity. Some developers think so; they are working to convert older office buildings into apartments.

For example, in New York one company has 1.5 million square feet of former office space in the pipeline for residential conversion. In Dallas, there are 3,163 housing units under construction in buildings that were previously offices. I have personally seen some of those conversions and they are quite nice, in walkable neighborhoods. This is unusual but good for Dallas.

Source: Bloomberg

Not every office building is suitable for conversion, of course. Many have issues with plumbing, windows, fire safety, and so on. Local zoning and other restrictions can also be barriers. But there’s still a lot of potential new housing supply in buildings no longer needed/wanted as office space.

The housing shortage isn’t so much a shortage as a misalignment. The people who work from home can live anywhere, but they want to be near amenities, shopping, etc. The service workers who make those areas attractive often can’t afford to live there.

This raises the price of, say, restaurant meals in downtown areas. Having more affordable housing in proximity to the places where non-WFH workers are in demand would definitely help suppress inflation. These conversions may be the fastest way to do it.

This is a topic we will have to cover over the coming year, as it is important. Stay tuned.

More By This Author:

Going Bang!Clashing Crises

Are We On A Collision Course With China?