Do Tariffs Raise Prices?

The argument that tariffs raise imported goods prices is exactly the same as the argument that gasoline taxes raise gasoline prices.

You might object that it’s theoretically possible that a given tariff doesn’t raise prices. That’s true. It is also theoretically possible that a gasoline tax increase doesn’t raise gas prices. In both cases, the seller might absorb 100% of the tax. The chances of that occurring in the real world are vanishingly small, especially for tariffs that apply to all countries.

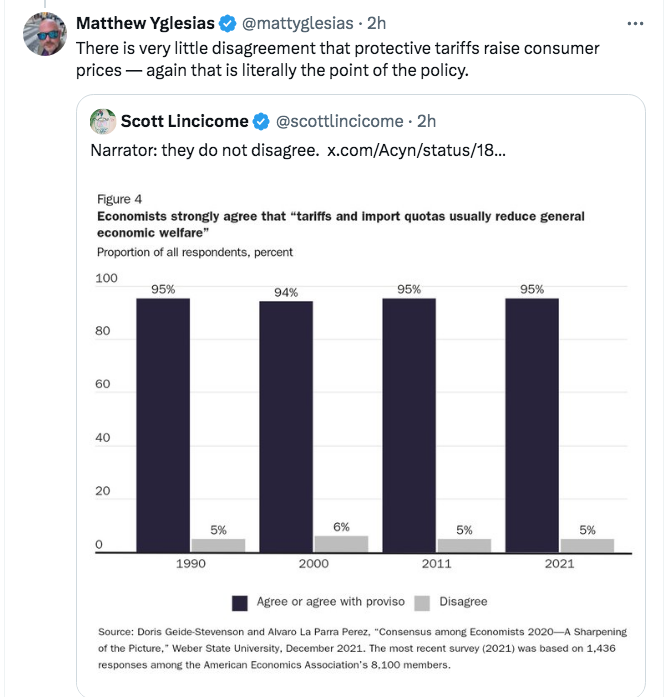

Matt Yglesias recently retweeted a Scott Lincicome tweet and added a comment:

Here I think Yglesias is greatly overstating the extent of disagreement. That might seem an odd claim, as he uses the phrase “very little disagreement” and points to a study that shows only 5% disagreement. Nonetheless, I still believe he’s massively overstating the degree of disagreement, which I suspect is actually far below 1%.

The poll question asked about the effect of tariffs on “general economic welfare.” A few economist (not many) favor tariffs because they think they might boost welfare. But that’s almost certainly not because they think tariffs will avoid raising prices. For instance, suppose an economist thought that the loss of blue color jobs to imports was a bigger problem than higher prices. It’s not a nonsensical claim, although I happen to think it’s wrong, partly for reasons expressed in my previous post. (I don’t believe it would save jobs.)

The small number of economists that do favor protectionism do so precisely because they believe a tariff would raise prices. If it didn’t raise prices, if it didn’t protect domestic industry from cheaper imports, then it would fail to protect jobs in import competing industry.

You might think I’m making a mountain out of a molehill, making too much of the difference between a 5% minority and something like a 0.5% minority. But I worry that people might assume that a proposition is almost certainly true if 95% of economists believe it to be true. If 50 economists out of 1000 hold a heterodox opinion on a given subject, it’s certainly not all that implausible that they might be correct—certainly much more than 5% odds. Consider a case where 95% of economists thought it was 75% likely that X was true, and 5% of economists thought it was only 25% likely that X was true. If polled, you might see 95% of economists saying they believe X is true, but in fact it would be only 75% likely that X is true, even if those 95% were completely correct.

I am part of a tiny percentage of economists that believe that the Fed caused the 2008 recession with a tight money policy. But even if a poll shows that 99% of economists believe that I am wrong, that would not suggest that there is a 99% chance that I am wrong. Indeed I doubt many of those economists who disagree with me would accept a wager where they could win a measly $102 on a $100 bet, on the question of whether an alternative monetary policy in 2008 could have prevented the big drop in NGDP, especially given that we weren’t even at the zero lower bound! (Yes, this would be hard to test, but imagine if there were a test.)

Polling economists certainly tells us something useful about what experts believe. But it’s important not to overstate the significance of a strong majority of economists lining up on one side of an issue. It’s not meaningless, but also not definitive.

PS. It’s also possible that a poll question on whether tariffs raise prices would also yield the same heterodox 5%, in which case it may be that there are a small number of economists who are simply highly eccentric. But I still believe the figure would be well below 5%, particularly if the two questions were asked back-to-back, reminding the economists being polled that they are two distinct questions.

PPS. Less than an hour after completing this post, I was reading The Economist and came across the following story about the Russian economy:

Russian GDP will rise by over 3% in real terms this year, continuing its fastest growth spurt since the early 2010s. In May and June economic activity “significantly increased”, according to the central bank. Other “real time” measures of activity, including one published by Goldman Sachs, a bank, suggest the economy is accelerating (see chart 1). Unemployment is close to an all-time low. Inflation is too high—in July prices rose by 9.1% year on year, above the central bank’s target of 4%—but with cash incomes growing by 14% year on year, the purchasing power of Russians is rising fast. In contrast with people in almost every other country, Russians are feeling good about the economy.

I’d estimate that back in 2022, far more than 95% of economists (including me) were wrong about how the Ukraine War and the resulting sanctions would impact the Russian economy. More often than not, 95% of economists will be right. But in a disturbing number of cases they are not.

More By This Author:

Goods, Services And TariffsHeterodox Views On Monetary Policy

Bullied Into Deflation