Demand Wasn’t Supposed To Be The Problem

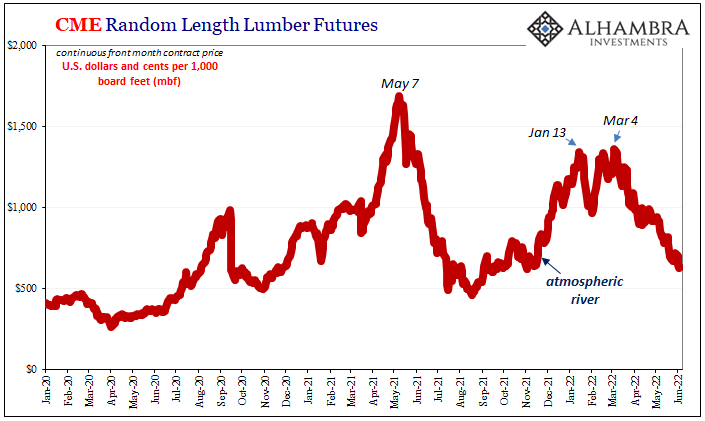

They called it an atmospheric river, though I’m not really sure who “they” was nor whether the term is scientific or just media hype. Either way, in early November the Pacific Northwest of the US along with Western Canada was inundated by a, well, river of rainfall. Mudslides, torrential downpours, just a muddy mess across the entire region. At one point all the major roads coming out of Vancouver had to be closed down, it was that bad.

This mountainous, heavily-forested section of the North American continent just so happens to be logger-central. After the supply and pandemic disruptions before then, a still-smoldering housing market desperate for new home supply (as a store of value predicated on the mistaken belief money-printer-went-brrrrr) suddenly faced yet another logistical obstacle.

The supply curve for lumber had just before then eased up, prices reflecting as much all throughout last summer. Jammed-up by sawmills running way below capacity, mid-year 2021 saw a trickle more capacity and some ease to the bottleneck.

Then along comes a real flood of rain rather than money. One Canadian company, West Fraser Timber, reported in November its weekly shipments across Western Canada had been curtailed by 30%, reflecting the reintroduction of gross inelasticity.

Lumber prices adjusted as they had before, small “e” economics demanding prices rise and for nothing to do with the Fed or either of the two nation’s nominal dollars.

By mid-January, the futures market for lumber felt like early 2021 all over again. The futures price more than doubled from its November low, rising back above $1,300 per thousand feet, within sight of last year’s epic top.

From there, however, the price stalled. Then March 3, crashing back down to earth again, lumber futures losing more than half since.

The fundamentals for lumber like a lot of commodities had been favorable on both sides of its economics. Supply bottlenecks and persisting pandemic plight would limit how much production could make it to market, inelasticity taken for granted as somewhat permanent, certainly durable thereby constantly susceptible to what otherwise would be normal disruptions – the atmospheric river seemingly validating the thesis.

Demand has been a complete afterthought, particularly with CPI rates running to 40-year highs. It was widely believed the only price risk pertained to those supply aspects since demand was assumed always going there, so much inflation-y hotness running rampant.

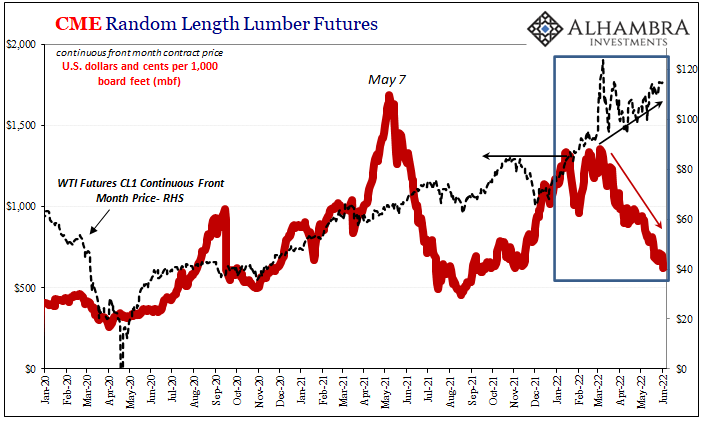

The kneejerk impulse will be to blame the Fed (or congratulate Jay Powell, depending upon your viewpoint) and its rate hikes (absurd QE hasn’t even begun). I mean, what would kill housing demand more thoroughly than to make the cost of homes more expensive?

Raise rates, the effective cost of buying a home jumps.

Except, isn’t that what lumber prices have been doing since 2020? According to the National Association of Home Builders, just between August 2021 and the start of 2022, skyrocketing lumber prices had already added a staggering $18,600 to the price of an average new single-family home in the US without a collapse in the real estate market for new construction.

Affordability isn’t some new problem introduced by aggressive hawks at the FOMC.

On the contrary, what we find more and more is that since early March – when financial markets went haywire for decidedly more-than-Russian reasons – demand for all number of things has gone soft, if not much worse.

Gasoline prices, the straw which finally buckled the increasingly weak economy.

Take container prices. Maybe nothing else better represents the gross supply inelasticity of the past couple of years quite like the shipping industry. Port snafus, blank sails, whatever, the price for renting a shipping container went utterly wild. It had calmed down only somewhat since last October, then rebounding until around February.

Since late February, however, container rates have been dropping at a nearly 45-degree angle. Freightos’ Baltic Global Container Index fell another 6% last week, sitting now below $7,400 for the first time since July. The all-important China/East Asia to US West Coast routes declined sharply, off 13% to just barely above $10,000.

Something has changed over the last few months.

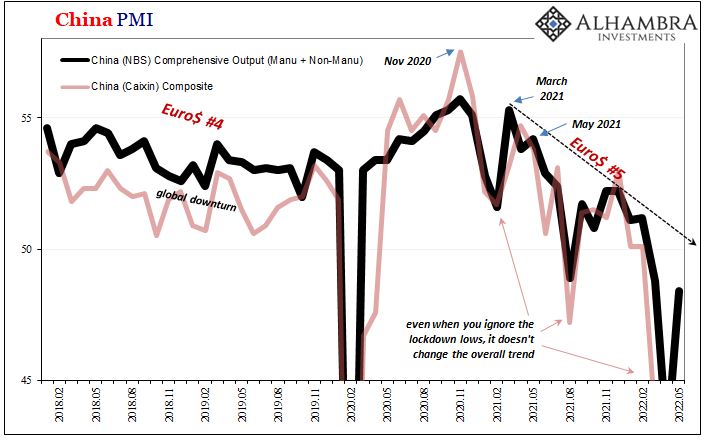

Short-run China-reopening euphoria is currently gripping financial markets – including US Treasuries to an extent. Many are betting that once COVID-free Chinese madness is lifted, the world goes right back to booming. Container rates instead say, wait a minute.

Demand is questionable, and this time from America.

Is it the Fed? As the global downturn becomes clearer, especially in its US capacities, everyone will point to (some blame, others applaud) monetary policy and rate hikes.

Correlation will be made into causation, just as it had been in the years following Paul Volcker’s confusingly wild monetary ride in the early eighties. Volcker had restricted bank reserves, the basis for the myth which still bears his name, but that didn’t mean squat beyond the Fed’s balance sheet.

All Volcker's reserve restrictions did was further add incentive for banks to use other forms of money which wouldn't require the need for the Fed's reserves. Stuff like wholesale repo and, of course, shifting even more money offshore (Euro$).

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) June 4, 2022

Result👇https://t.co/3UjkO31dzq pic.twitter.com/cEPdoFvD13

Yield curve inverted. Fed cutting bank reserves. Big money questions. Consumer prices a huge problem.

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) June 4, 2022

2022?

No, 1981.

Powell wants to put his name up next to Volcker's. Careful what you wish for, Jay.https://t.co/3UjkO31dzq

At a loss to explain what happened, nasty recession and all, officials knew it wasn’t bank reserves so they began (years later) to wonder if maybe it had rather been the rate hikes (specifically real interest rates) that came about as the byproduct of constricting reserves. Assuming cause from coincidence, the 1981-82 recession has since been labeled an intentional Federal Reserve act.

Volcker, at least, got the fed funds rate up to around 20%; Powell isn’t even in range of two.

CPIs by 2022 had everyone thinking demand was invulnerable, white-hot to the point of needing a good dousing. Only now, almost halfway into the year, it’s becoming very clear there wasn’t much heat ever to begin with. Instead of both supply and demand characteristics being so forever favorable in commodities like the global economy on the whole, doubts on both sides manifest and increasingly as it relates to demand over supply.

Inventory, after all.

The Fed didn’t kill inflation and recovery with just two rate hikes (thus far). The fragile economy never recovered and finally, the negative pressures from general supply shock-driven prices went one step too far (that step begun in mid-January).

Once it becomes clear (again) China’s not in any shape to come riding to the world’s rescue, then globally synchronized moves on to its next stage.

Disclosure: This material has been distributed for informational purposes only. It is the opinion of the author and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any ...

more