Deflation Talk

If you could ask the world’s top central bankers what really terrifies them, I think the honest answer would usually be “deflation.” It is their greatest nightmare. They think a little inflation is good (thus the 2%+ target), and they’re confident they can subdue it if necessary. Deflation is a bigger problem.

Let’s note, however, that these aren’t either/or conditions. They have degrees of severity. Indeed, the last four decades we’ve seen disinflation—a mild form of deflation—in many segments of the economy. Compared to that, even relatively mild inflation looks quite concerning. And many smart people are concerned, as I described in last week’s review of SIC inflation talk.

Today we’ll consider the other side of the SIC inflation/deflation argument.

It's All Just Math

Dr. Lacy Hunt of Hoisington Management is a perennial SIC favorite, and for good reason. He’s been consistently right about inflation (little or none), interest rates (flat or down), and Treasury bonds (bullish) for decades. He built that track record by simply standing his ground. To Lacy, it’s all just math: The equations have specific answers and thus do his investment choices. That may sound easy, but it takes a lot of courage.

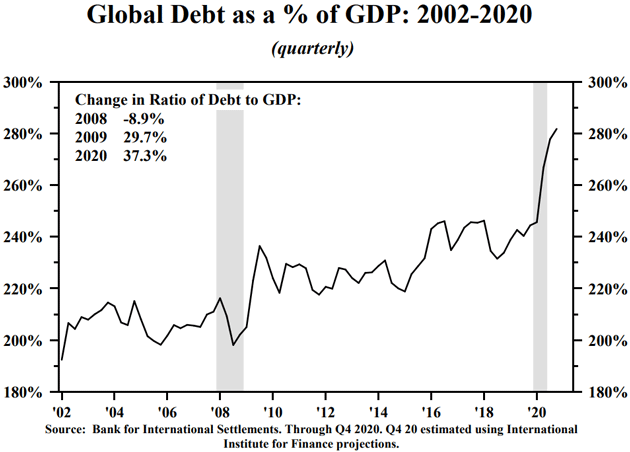

In Lacy’s view, today’s core problem is that excess debt suppresses economic growth, without which demand can’t rise enough to generate inflation or push up interest rates over the medium term. This is a structural problem, which at this point we really can’t fix.

Source: Hoisington Management

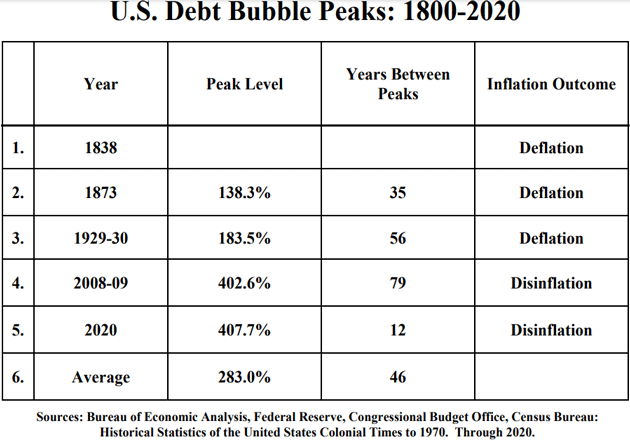

Going back further, Lacy showed the US has experienced five major debt bubbles in the last two centuries, all of which led not to inflation, but to disinflation or deflation.

Source: Hoisington Management

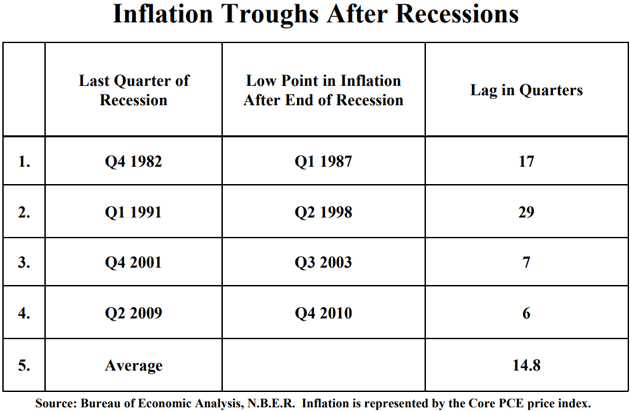

Lacy also pointed out that inflation is actually a lagging indicator. It doesn’t usually turn higher until well into a recovery phase.

Source: Hoisington Management

This runs counter to today’s popular narrative (discussed last week), which says to expect strong recovery and rising inflation at the same time. Lacy explained why that doesn’t happen:

"The typical lag between the start of a recession and the low point of inflation is almost 15 quarters and even when the lags are shorter, only six to seven quarters, in those particular two cases, the inflation rate was still near its low, two and three and four years later. And there's a good reason why inflation's a lagging indicator.

"If you go into a recovery or attempt to recover, and the inflation rate takes off, that will truncate the recovery. You'll have a wider trade deficit, inflation will push up interest rates and that will work against the recovery. And since prices rise faster than wages, you reduce real income. In other words, to have a major acceleration in inflation means that the expansion will not hold."

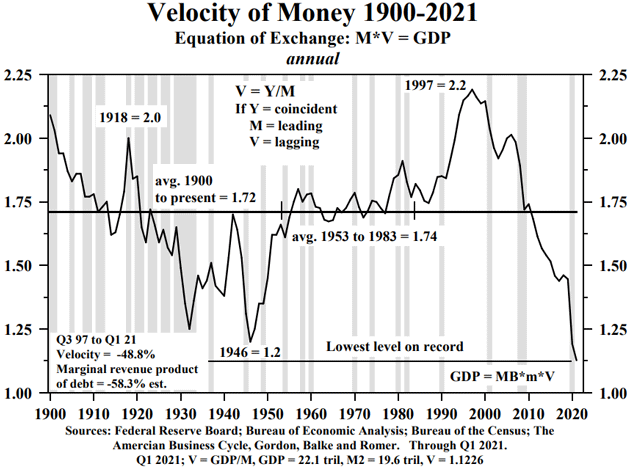

Lacy also explained why he isn’t worried about the increased money supply. It gets back to his point on debt. The amount of money is less important than the speed with which it circulates, or “velocity,” which is at the lowest level ever.

Source: Hoisington Management

At least 10 years ago Lacy and I were talking about what it would take to get the velocity of money lower than during the Great Depression or post-World War II. We were both watching velocity slow significantly and I was curious as to when that would end. Lacy explained at the SIC:

"We have to take into account what's happening to the speed at which money turns over and the velocity of money hitting an all-time low. And what is causing velocity to decline is that we're taking on too much debt, it's triggering diminishing returns and non-linear relationship and this pulls the marginal revenue product of debt down and it also takes the banks out of the process and that pulls velocity lower."

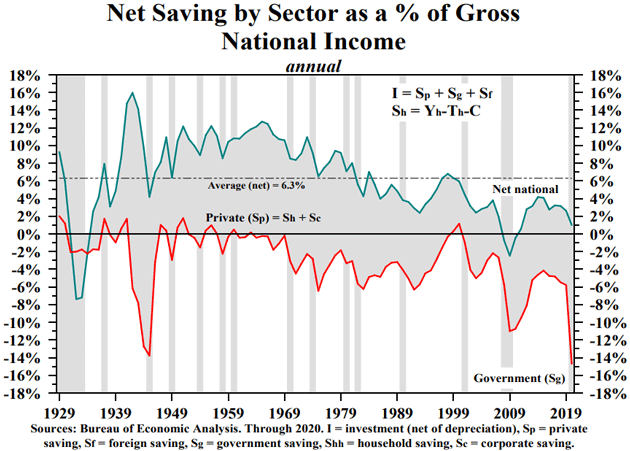

Another problem, Lacy believes, is that debt reduces savings. His next chart takes some explaining. I’ll quote him right below it.

Source: Hoisington Management

"The critical variable for the macro-economy is net national saving. And net national saving has three components. It has the gray shaded area which is the private sector; household incorporated; and then the government deficit which is the red line and the green line is the sum of the two. Now, look at the little equation at the top of the page. This is one of the most important fundamental relationships in economics and it says (in effect—JM) 'I, physical investment, must equal saving out of income.'

"If you do not have saving out of income, you cannot get sustained growth in investment. Without sustained growth in investment, the standard of living does not rise. Now, the deficit as a percent of national income, the red line, was over 14%. That took out the percentage peak during WWII. The green line is the sum of the three and you'll notice it's just barely above zero.

"And if you look at the chart, which goes back to 1929, you'll see there's only two situations that are worse, during the 1930's and also during the late 2000's. We simply do not have the resources to fund ourselves and to obtain a higher standard of living, which means that the economy will falter as we go forward, inflation will move lower."

Lacy is the rare PhD-holding economist who doesn’t hedge. He looks at this almost like physics: Gravity always wins. So when he says the economy will falter and inflation will move lower, he is confident in the same way astronomers are confident about planetary orbits. While in theory something could interfere, the odds are (astronomically) low.

Lacy agrees we could see some transitory inflation this year. He doesn’t see it lasting long, and Fed policy doesn’t especially matter. We are beyond that point. Here’s Lacy wrapping up:

"If the Fed wants to raise interest rates, they can slow economic activity down. However, when economies become extremely over-indebted and debt levels are rising very dramatically, the velocity of money falls. And that keeps shifting the aggregate demand curve inward. The fact of the matter is there is no mechanism other than for a very limited period of time by which the inflation rate can go higher."

In other words, as long as excess debt is pushing velocity lower, aggregate demand will keep falling. Sustained, broad inflation is impossible under those conditions—though there could well be temporary inflation in certain segments. I would love to tell you why Lacy is wrong. I can’t. Many have tried and he’s outlasted them all.

A Price Level Adjustment

Dave Rosenberg isn’t in the inflation camp, either, for some of the same reasons as Lacy Hunt and a few others, too. It was a good part of his slide presentation which you can view here.

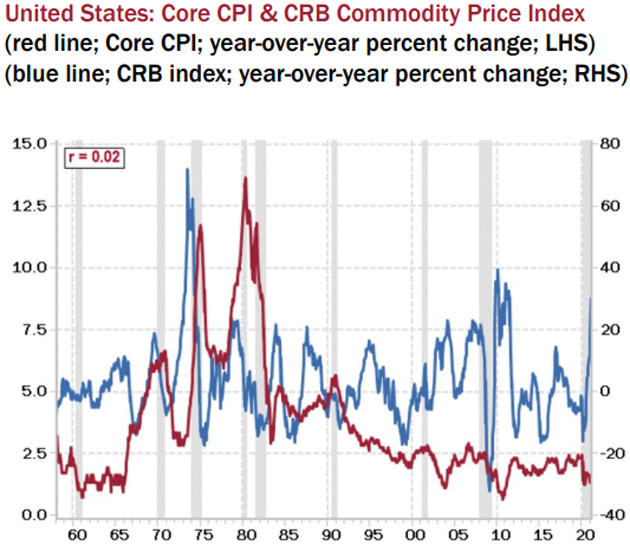

On the idea that rising commodity prices will drive inflation, Dave had two responses. First, commodities actually have no correlation with inflation. We have many examples of one rising without the other.

Source: Rosenberg Research

Dave thinks the present commodity gains are mainly speculative demand, driven by the pandemic money that is burning a hole in investor pockets. And to the extent there really is new commodity demand, it comes mainly from China, where the kind of growth that needs raw materials seems to be waning.

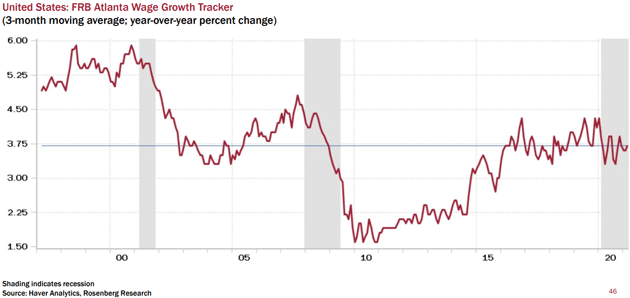

On wages, Dave says the growth we hear about must be anecdotal because it’s not yet evident in the data.

Source: Rosenberg Research

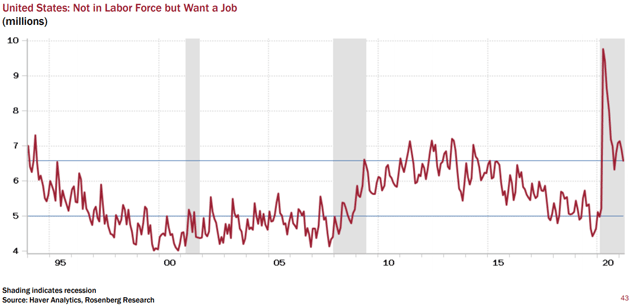

Nor does Dave expect to see much wage pressure, given the large number of workers still on the sidelines. Aside from the many officially unemployed, millions more are working part-time and would expand their hours if possible. Another 6–7 million left the labor force but say they want a job.

Source: Rosenberg Research

The number of available workers should grow considerably in the next few months as vaccinations make jobs safer, schools reopen, and enhanced unemployment benefits expire (which is already happening in many states).

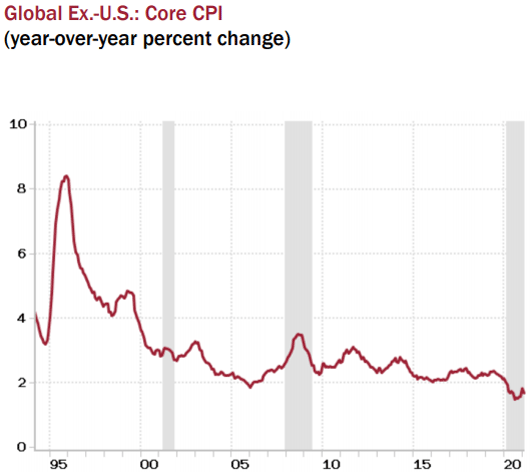

That should, at the very least, cap aggregate wage pressure without even counting the many ways businesses have become more efficient and automated. Certain industries like restaurants and hotels are indeed seeing wage pressure, but Dave thinks it isn’t enough to affect the broader picture. Finally, Dave pointed out that the CPI pressure we see right now is almost exclusively a US phenomenon. The rest of the world just isn’t feeling it.

Source: Rosenberg Research

This might be related to the US emerging from the pandemic faster than most others. But CPI elsewhere (the local versions of it, at least) is still well below ours even in places where COVID-19 had a smaller effect. The US is the world’s largest economy, but we don’t stand alone. It is hard to imagine a scenario where the US has significant inflation and the rest of the world doesn’t.

Dave is sticking to his guns on this. In his May 25 daily letter, he argued we are seeing a “price level adjustment,” not real inflation.

"It seems as though, out of the blue, we have gone from talking about deflation to inflation. From depression to an economic boom. From the Bubonic Plague to the 'Roaring Twenties…'

"As for the inflation situation, what I come away with is that what we are seeing is a price-level adjustment coming out of the pandemic and the price data can easily be explained by an economy reopening in the face of several supply constraints. The Fed has made a great case and prepped the markets and the general public prior to the data as to why this is not a lasting supply-demand imbalance.

"This is not real inflation we are seeing; we are seeing tremendous distortions and disturbances in the data that are being skewed by the lingering effects of the pandemic and everything that has followed. And I have to say that the Fed has been masterful in laying this out; whether you want to agree with them or not is a different matter, but this is one of those times when I do."

If Dave is right that we’re just seeing “disturbances in the data,” it ought to clear up in the next few months, and certainly by year-end. I suspect he will rethink his position if CPI is still rising in December. But for now, his points are hard to dispute.

Cathie Wood on Deflation

The name Cathie Wood of ARKK fame typically makes you think of technology stocks, not macroeconomics. Yet she has serious macro chops, having studied under Art Laffer at USC and her first job was as an economist. At the SIC, Cathie talked about the deflationary pressures she sees in her technology research. Let’s read from the transcript, with my editing.

"Just one more thing on interest rates and inflation, I think we're going into a deflationary period after this supply chain related and base effect related bounce in inflation…

"Today's inflation numbers, I'm sure to many people, were shocking. Just looking through it, it seemed very much supply chain oriented. Car rental, transportation costs, and so forth. We think that the core CPI inflation will stay in the 3% to 4% range for the next few months, and PPI inflation headline could be anywhere from 6% to 10% on a year-over-year basis.

"But I think we've never seen such serious supply chain issues as we're seeing now. Think about it. A year ago, the economy effectively just shut down. During '08, '09, it was shutting down. It was a slow move into that cathartic moment. This was just cold turkey.

"Businesses cut off all orders, and what happened was the consumer saving rate soared to 34%, 35% and the consumer had very few places to spend. Goods. Goods were the spaces to spend, right? Durables and non-durables, especially for the home and so forth. Well, that's where they spent a disproportionate amount of their budget relative to normal.

"Goods are only one-third of consumption in the GDP accounts. Services are two-thirds. What I think is going to happen now is businesses are scrambling like crazy to keep up with demand. They can't. They got way behind. They're… double and triple and quadruple ordering. That's the first thing. The consumer, yes, has been spending aggressively on goods, but probably is about to shift the mix back towards services, maybe disproportionately.

"I think we're going to end up with a massive inventory problem towards the end of this year or into next year. We see three sources of deflation on the horizon. The first is that one, and that's inventory-driven and very commodities-oriented.

"The second is what we call good deflation. Good deflation is associated with technologically-enabled innovation. Wright's Law is really important to us. It says for every cumulative doubling in the number of units produced, costs associated with technologically-enabled innovation decline at a consistent percentage rate.

"Huge deflationary forces that are going to increase access as prices come down, and unit growth therefore will explode in those areas. The bad deflation is the corollary to that, and that is, we believe as much as 50% of the companies in the S&P 500 are going to be disintermediated or disrupted by the five innovation platforms around which we have centered our research: DNA sequencing, robotics, energy storage, artificial intelligence, and blockchain technology.

"They are in harm's way, and they probably, because they are more mature, since the tech and telecom bust and the '08, '09 meltdown, they have basically complied with short-term-oriented investor demands. They want profits, they want them now. They want dividends, they want them now.

"To do so, companies leveraged up. Now many of them are going to be in harm's way. In order to service debt, they'll have to cut prices. We see major deflationary forces evolving here. I know on a day where the CPI has gone up 0.8 and then 0.9 in core, many people might be looking at this and wondering.

"But this is what we do all day long. We know the good deflationary forces are in place, we know the bad deflationary forces are in place, and now we believe, given what we're seeing with inventories, double, triple ordering, that there's another deflationary bias that's being built into the system, but probably won't play out until later this year, next year."

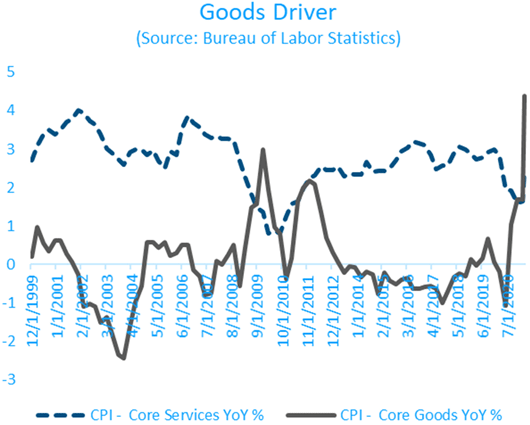

To Cathie’s point, much of the recent inflation is coming from “goods inflation.” Here’s a chart from Sam Rines on the year-over-year core services and core goods inflation. Notice the steep rise in core goods.

Source: Avalon Advisors

The important takeaway here is the concept of year-over-year (YoY). Twelve months ago, we were in a deflationary collapse, as Cathie noted. I think we will likely see “wage inflation” over the next three to six months. I personally think that’s good, since it will mostly be in the lower income tiers.

It’s reasonable to assume those wage increases will be “sticky.” But the balance will swing back to management as unemployment benefits diminish. They may be stuck with those past sticky wages (pardon the pun), but I doubt wages will keep rising.

So a year from now, services and wage inflation may both return to levels more like the disinflation of the past few decades, because we are looking at year-over-year numbers and not five years over five years or whatever. It’s just the way we measure things. The Fed will declare victory and go home.

If that’s not what happens, the Fed will have to do more than think about thinking about rate increases, and actually do it. This has nearly always led to an eventual slowdown in the economy, and disinflation.

Either way, we end up at the same place over time. The Fed should start the tapering process and then slowly raise rates, trying to get someplace that looks more like normal. Given the massive budget deficits Congress seems hell-bent on running, I am not certain how we get there. Trying to raise rates in this environment will be excessively volatile.

The Right Question on Deflation/Inflation is When

So where does this leave us? Can we somehow reconcile these widely varying inflation forecasts? Maybe.

On the last day of the SIC, we heard from William White, former Chief Economist at the Bank for International Settlements and holder of many other global economic honors. I call Bill my favorite central banker because he is one of the few who can actually speak clearly. He cuts through the jargon and makes complex ideas seem simple.

On inflation, Bill explained all these forecasts could actually be right. The key is to consider the sequence in which they will happen.

- In the near-term, we could very well see significant inflationary pressure for the reasons outlined by Peter Boockvar, Jim Bianco, Louis Gave, and others.

- But in the medium-term that follows, the math Lacy Hunt describes will catch up, squelching inflation and maybe forcing deflation.

- While in the long run, monetary excess and the need to liquidate debt could send inflation sharply higher, possibly to the point of hyperinflation.

That makes sense to me. I’m not as worried about hyperinflation as Bill is. However, if Treasury, Congress, and the Fed should somehow institute actual MMT (as opposed to QE), I would become hyper-worried, pardon the pun.

Of course, identifying the transition points between each phase will be critical, and likely difficult. But it’s an important reminder not to treat your inflation outlook like unchanging religious dogma. The world economy is a “complex adaptive system,” to use one of Bill White’s favorite phrases. Its behavior evolves as it reacts to new events.

So if someone asks, “Do you expect inflation?” maybe answer with a one-word question of your own: “When?”

Disclaimer: The Mauldin Economics website, Yield Shark, Thoughts from the Frontline, Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest, Outside the Box, Over My Shoulder, World Money Analyst, Street Freak, Just One ...

more