3 Bubbles Building In The U.S. Economy

Although the market indices have been hitting record highs, there are structural problems that continue to build in the United States economy that may severely impact customer spending and corporate earnings in the next several years.

This article will outline three bubbles that are growing in the economy, along with a few potential ways to reduce your investment exposure to them.

None of these are “doomsday” bubbles, and each of them on their own is manageable; it’s the sum of all of them together that seems to be shaping up to cause long-term economic malaise if left unaddressed.

Bubble 1) Student Loan Debt

The cost of higher education in the country has increased 4-5% per year over the last decade, dramatically outpacing inflation.

To account for this (and possibly also fueling some of this increase, as some would argue), the federal government has expanded its loan asset balance by tenfold in the past decade, from around $100 billion to over $1 trillion.

This is a rapid acceleration in a short period of time and puts the younger generation in uncharted territory as far as debt is concerned:

Federal Student Loan Assets

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

Student loans including from both public and private sources now exceed $1.3 trillion, and account for a larger segment of debt than either auto loans or credit card debt. They are harder to discharge in bankruptcy than other types of debt, and have no collateral.

There are over 44 million Americans with student loans, and the average per-student debt at graduation among students that have loans is over $35,000. And although it disproportionally affects people under 40, approximately one third of total student debt is held by people over 40 years of age. Plus, parents are often co-signers for the loans of their children, which exposes them to the risks.

According to the Wall Street Journal, 43% of student loans are either behind in payment or have received permission to defer payments due to financial hardship.

This bubble can impact stock returns in two key ways:

- It will act as an anchor on consumer spending for decades that didn't exist in prior generations.

- Because it has gotten so large and continues to grow at a pace that exceeds inflation, the bubble could pop, resulting in a large percentage of loans not being paid back. This would impact federal revenue and increase the federal deficit.

Bubble 2) Per Capita Healthcare Costs

The US pays far more per capita for healthcare than literally any other country in the world; approximately double the average of other developed countries:

Source: Peter G. Peterson Foundation, citing OECD data

And yet, the US does not have better health outcomes than average; life expectancy is mediocre and infant mortality is not that low, among other metrics.

Measuring healthcare effectiveness is a complex subject, but clearly the US is not getting its full money’s worth. Visual Capitalist has an excellent chart that shows how the US has fallen behind in life expectancy while doubling the healthcare costs of every other developed nation.

Many companies charge far higher prices for drugs in the United States than they charge elsewhere, because we lack the same level of price negotiation as many other countries have. In this sense, we subsidize other countries.

More alarming is that this spending continues to grow at nearly 6% per year. Healthcare spending as a percentage of GDP was 12% in 1990, and it’s now up to 18% of GDP just a quarter century later, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. This is expected to increase to over 20% of GDP by 2025.

The Affordable Care Act succeeded in insuring more people, but hasn't truly addressed any of the primary cost drivers and thus did not rein in costs.

Disproportionately increasing healthcare spending obviously benefits the healthcare sector for now, but acts as a drag on consumer spending for the rest of the market. Plus, if this proves to be unsustainable, it would eventually unravel in painful ways for the healthcare sector as well.

As the country with the highest per-capita spending on healthcare, with costs continuing to skyrocket, we're in uncharted territory here as well.

Bubble 3) Unfunded Pension Liabilities

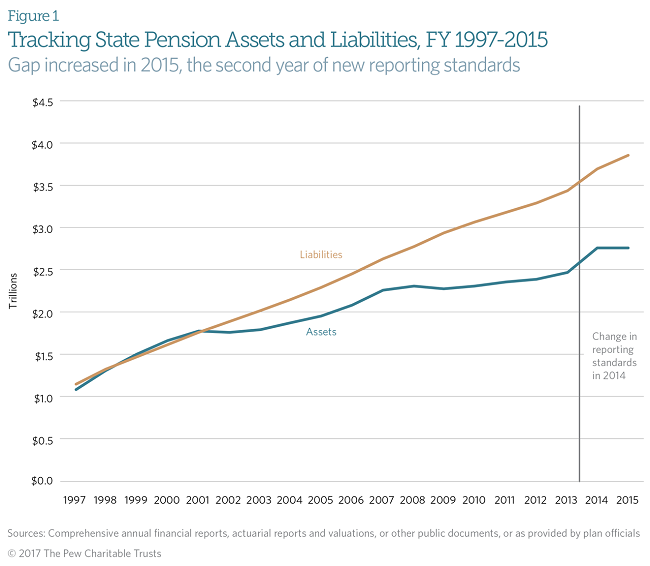

According to Moody’s, public net pension liabilities total $4 trillion, and even in the "best case" scenario of strong stock returns over the next few years, net liabilities won't go down.

In fact, according to the same report, if markets fall by 5% in 2018 and stay flat in 2019 (which is not even a particularly brutal scenario), there would be a 59% jump in net liabilities.

Here's a chart by Pew Charitable Trusts showing the growing divide between state pension assets and liabilities:

According to Ben Carlson, CFA, the Director of Institutional Asset Management at Ritholtz, "there are going to be many, many pension plans that run into trouble in the years ahead. It’s simple math."

This is mainly due to states having overly optimistic rate of return estimates for their investments, and not paying enough into the system to support their promised pensions. Most public pension funds plan for 7-8% annualized returns on average for their portfolios that consist of both stocks and bonds.

John Bogle predicts about 4% annualized S&P 500 returns over the coming decade, citing high market valuations as the reason. That's far lower than the 7.5% that pension funds are planning for from a portfolio of bonds and stocks, on average.

McKinsey & Company predicts 4-6.5% returns for US and European stocks and 0-2% for bonds over the next 20 years.

The Shiller P/E ratio and Capitalization/GDP ratio of the market agree with these numbers; both of those indicators are significantly higher than their historical norms, indicating a high probability that forward returns over the next 10-20 years won’t be very good.

Source: Data from Robert Shiller, Graphed here Lyn Alden

Earnings multiples simply don’t have room to run much further, so we’ll be constrained by actual corporate earnings growth rates and possibly have them offset by mild or moderate declines in earnings multiples.

Plus, we are 8 years into the fourth longest economic expansion and bull market in US history. The longer we go, the odds move against us in terms of sustaining this without an economic recession and valuation correction. And when that correction happens, the pension funding gap will widen even more, at least in line with Moody's negative scenario of a 59% increase in 2 years.

$4 trillion in pension liabilities divided by the 127 million full-time US workers is over $30,000 per worker. If that figure jumps to $6 trillion, then we're looking at a per-worker figure that exceeds $45,000. The tax burden to correct this without major pension cuts would be huge.

Of course, nobody can predict for sure how long an economic expansion could last, or how long stocks can remain expensive. Low interest rates could conceivably keep it going for a while. If I were writing this in 1997, I could have been saying, "market valuations haven't been this high since 1929!", and yet it would have taken another 3-4 years for that bubble to work itself out and come back down.

The longest sustained economic expansion in US history occurred for 120 months between 1991 and 2001. If we hit June 2019 without a recession, we'll officially be in the longest economic expansion in US history. And when an inevitable contraction comes, and a market correction occurs, the gap is going to quickly widen in state, local, and corporate pension funds.

Bringing this back to pensions, their assumptions for their rate of return are not conservative enough. They're assuming a higher rate of return (over 7% for a mix of stocks and bonds) than what a significant amount of evidence suggests the probable range of future returns will actually be, which means their funding gaps will likely keep widening unless they have significant reforms.

Putting it all together

What all three of these bubbles have in common is that they will impact middle class consumer spending, with no end in sight.

The rate of home ownership has fallen to its lowest point since 1965 despite the availability of rock-bottom mortgage rates, and a big factor is that younger families have too much student debt to take on the obligation of buying a house.

The public debate on how to fund healthcare and who should pay for it is among the most bitter of partisan issues, partly because we have the highest healthcare costs in the world and it's costing people at least an extra four thousand dollars per year compared to just about any other developed country in the world.

The pension debacle is not yet affecting most people. It's accumulating red ink, and neither taxpayers nor pensioners in most regions have been hit with its effects yet. When this hits a point where it needs reform, it will add yet another burden onto the public to either pay for these pensions or cut the pensions, and either of those scenarios will impact middle-class consumer spending.

Investing strategies to stay ahead

A rational investment strategy in this type of macro environment needs to be ready for the possibility of a market correction, and needs to be able to make good returns even in flat or choppy sideways markets without trying to do any timing predictions.

Historically, almost every time the Shiller P/E ratio or Capitalization/GDP ratio hit the levels that they are at now, returns over the next 10-20 years were poor. Combine that fact with these increasing structural problems that are hollowing out the middle class spending engine of the economy, and we’re almost certainly headed for a significant correction or period of flat returns.

Maybe within six months, or maybe in 3 years or more. I don't know, and I don't pretend to know.

Bonds, however, aren't necessarily the safe haven that they've traditionally been. Over the past 35+ years, they have benefited from high and falling interest rates.

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

Now that interest rates have hit zero and are inching back up, bonds barely keep up with inflation and may face extra volatility in the years ahead, because bond prices are inversely correlated with changes in interest rates.

Until the federal funds rate comes back up to 2 or 3%, bonds simply don't interest me as an investment from a risk/reward standpoint. I have some in my indexed retirement account, but none in my hands-on active portfolio.

In addition to holding onto a diversified portfolio and not making any significant market-timing predictions, here are a few specific tactics I'm using to make decent returns in current conditions.

Strategy #1: Sell Cash-Secured Puts

Rather than buy companies at today’s overvalued prices, you can sell put options and get paid to wait to enter companies or ETFs at a lower cost basis.

The benefit of this approach is that you don’t have to try to time the market by trying to predict exactly when a recession or correction will occur. You simply keep selling puts, making a double digit rate of return during a flat or upward market, and then automatically buy into stocks when they fall to undervalued prices.

My portfolio, for example, is designed so that if equities fall 20%, my portfolio will most likely only fall 10% or so, and yet I continue to make about 12% annual returns if the market keeps going up or stays flat. That's a really worthwhile risk/reward balance, and helps counter the likelihood that stock returns over the next decade or two will be poor based on current valuation levels.

This is an optimal strategy for markets like this that are highly valued and that may trend sideways or down for some time. Even if the market continues to be priced upward for a while, you’re still making money in that scenario as well.

Strategy #2: Reallocate Some Capital From Stocks to Real Estate

Real estate in many US markets is reasonably priced, especially outside of certain coastal cities. Although home prices are back up to their high point prior to the 2007/2008 drop, stock prices have outpaced home prices, mortgage rates are still low, and so the expected rate of return may be better for mortgaged real estate than stocks over the coming decade.

REITs as a sector are also a solid investment at their current valuations, in my opinion. Unlike the rest of the stock market that has remained fairly euphoric, REITs underwent a correction in mid/late 2016 due to fears of rising interest rates.

In 2015 through the first half of 2016 REITs were overvalued, but after a sell-off in mid-2016, they are more reasonably valued with decent dividend yields. In contrast, stocks have only gotten more and more expensive.

Rotating some capital out of stocks and into REITs is potentially a smart move at this point.

Strategy #3: Look Abroad

Every market in the world has a different CAPE currently, along with their own strengths and weaknesses as a region. The US happens to be one of the most expensive markets in the world, but with some of the strongest trends in its favor. For example, technology makes up a larger portion of the U.S. economy than many other developed countries, and technology stocks tend to command high valuations due to their growth rates.

But, taking some money off the table in the US to make sure you have a decent amount of international exposure may be warranted.

One problem with global stock indices is that because they are purely market-cap weighted, many of them are heavily concentrated in Japan, which has a shrinking population. They're not properly diversified, in my view.

There are some international indices that set other conditions to the stocks. So for example, because Japanese companies don't pay significant dividends, if you include a dividend metric in your automatic stock selection, you'll naturally underweight Japan, or at least not overweight it like most international index funds do.

The Vanguard International Dividend Appreciation ETF (VIGI), Vanguard International High Dividend Yield ETF (VYMI) and the iShares International Dividend Select ETF (IDV) are all dividend-focused international picks that avoid over-concentrating in Japan.

Any updates?

Enjoyed this, would like to see more by you.

Lets hope we learn from previous bubbles.