TIPS Spreads Are A Big Problem

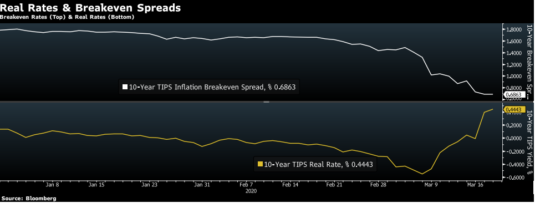

Michael Darda sent me a scary graph showing 10-year TIPS spreads (white line) and the (real) yield on 10-year TIPS (yellow line):

Notice the recent sharp increase in real interest rates in the US. This is exactly what happened in late 2008. Indeed almost everything that’s happened recently in the financial/commodity markets is a replay of what happened in late 2008.

But the rise in real interest rates is especially interesting. When I point out to economists that nominal interest rates don’t measure the stance of monetary policy, they sometimes say, “Yes, but real interest rates do.” Actually they don’t, as Ben Bernanke once explained.

But if real interest rates did measure the stance of monetary policy, then policy would have been getting much tighter. Do my colleagues in the economics community agree with me that monetary policy has been getting much tighter? No, of course not.

When I used to point out to people that real interest rates rose sharply between July and November 2008, they looked for 101 excuses to explain it all away. They say that TIPS didn’t accurately measure ex-ante real interest rates. Really? TIPS are 100% default risk-free, and the real rate of return is locked in. In the entire investment universe, there is no asset that measures risk-free ex-ante real interest rates more accurately than TIPS. But they just knew that money couldn’t possibly be getting tighter, so there had to be some other explanation.

Now it is true that the TIPS spread can get distorted during periods of high demand for liquidity, and that the current 0.62% 10-year TIPS spread may not accurately measure inflation expectations. (Note that the TIPS spread is for CPI inflation; it implies a PCE inflation rate of barely over 0.3% over the next 10 years!)

But even if the TIPS spread is distorted, it doesn’t mean money is not too tight, it just means that it’s too tight for a different reason. Both of the two possible reasons for low TIPS spreads (low inflation expectations and a mad rush for the more liquid conventional bonds) suggest that money is currently way too tight.

Some will insist that conventional Treasuries are the measure of all things, including real interest rates. That’s as nonsensical as someone in Zimbabwe in 2008 claiming “all asset values are soaring higher”, not recognizing that actually the value of one specific asset:

is plunging much lower.

Similarly, 99% of assets in the world are like TIPS, with rising real yields, not like Treasuries, with falling real yields. There in no meaningful sense in which one can deny that real interest rates in America are rising. That doesn’t prove that money is tight, but it suggests that people who view the stance of monetary policy through the lens of interest rates ought to view it as tight.

In my view, NGDP expectations over the next few years best measure the stance of monetary policy, and of course they are also falling.

PS. If you are in an investment area where liquidity doesn’t matter, say a company investing for insurance or pension obligations 10 years out, why wouldn’t you prefer TIPS over Treasuries right now? Isn’t PCE inflation likely to exceed 0.3% over 10 years? I’d be interested in responses from someone in the investment community.

PPS. George Selgin wrote an excellent post in response to Bob Murphy’s critique of market monetarism.

Bob wanted an example of where NGDP targeting would fail to stabilize NGDP. Suppose you are targeting 2-year forward NGDP expectations, and NGDP in Q2 and Q3 of this year fell sharply. Then the policy would fail to stabilize current NGDP. So there’s nothing tautological about our defining tight money as low expectations of future NGDP growth.

PPPS. David Beckworth has a new Mercatus Policy Brief discussing ideas for addressing the impact of the coronavirus on NGDP.

PPPPS. I have a new Mercatus Bridge post on the need for new Fed policy tools.

Falling NGDP was something the Fed ignored in 2008. I wonder if they will do the same thing now?