The Art Of The Startup Pivot

Startup (noun): a work in progress

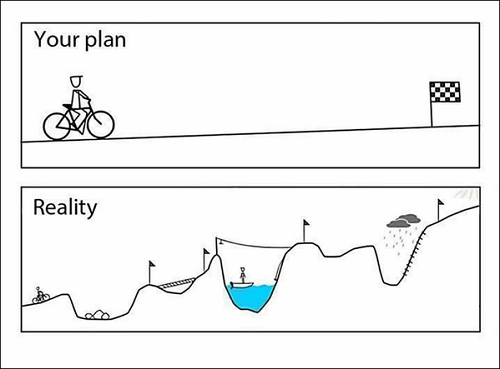

At the stage I prefer to invest (early), the ride is expected to be bumpy.

Only a few startups will execute near-perfectly on their original goals. More will take a while to get there.

Along the way some will fail. Investors will take losses. It’s simply part of the math in early-stage investment.

But many startups will hover in “purgatory,” for lack of a better word. They’ve raised money, but haven’t found “it” yet. Not enough of it to justify a legitimate series A fundraising round, at least.

For whatever reason, the startup is losing momentum. It may have a talented team, but what it got ain’t selling…

What to Do?

To understand what happens next, you need to think like a Silicon Valley startup employee.

Most are young and ambitious. They didn’t just randomly happen to work at a startup company; this is what they wanted.

They’re often single, with valuable career skill sets. So if they think a startup is faltering, some will start to eye nearby patches of green(er) grass. After all, they don’t have much holding them back; quite the opposite.

If there’s a glimmer of hope, however, believers will stay.

Sometimes that glimmer is an investor who has become a believer him or herself. More cash, and a renewed push, may give the team the time they need to figure the product out. I’ve seen this scenario play out well (and not so well).

But occasionally that hope comes in the form of a pivot. A total change in direction. Reboot with a new mission.

Desperate Startup Choices

Let’s say a startup’s momentum has evaporated. The thrill is gone. Traction is like a 1992 Ford Taurus with bald tires trying to climb out of the mud.

Employee dreams of stock options exploding in value have turned into visions of failure. Investors are wondering what’s next?

Three options here.

- Shut down and return remaining capital to investors.

- Ignore the problem, keep plugging away and collect a paycheck while it’s there.

- Pivot and change the business plan radically.

Choice No. 1, shutting down, isn’t as bad as it sounds. It’s often the best option.

Example: A startup I invested in less than a year ago recently shut down. In this case, the company will pay back roughly $0.58 on the dollar.

It wasn’t a bad outcome. Unfortunately, the economics they hoped would be there weren’t. So they decided to close up shop. To my mind, no bridges were burned. I’d consider investing in the founders again. They tried something ambitious and failed fast. I’ll take a 42% loss on capital over a goose egg any day. That’s a lesson Bill Bonner (founder of our parent company) would appreciate. I’ve heard him say “fail fast” more than once.

Choice No. 2, ignoring the problem, is the most worrying. Not likely to end in a positive way.

Choice No. 3, the pivot, is always interesting. Startups who like their current team and investors, and decide to take a shot at something else entirely…

The Pivot

Occasionally it’s an amazing thing.

A lagging startup founded in 2005 called Odeo evolved into the $23 billion social media giant Twitter, for example. Odeo was previously a directory for audio/video media syndication. Founders saw it wasn’t working and flipped the script.

Here’s another one. In 2010 a guy named Stuart Wall founded a startup. He called it Postabon.

It was going to be a “daily deal” site. Similar to Groupon.

You have to remember, this is back when Groupon was the next big thing. Its growth was off the charts. At one point that year Google offered to buy it for $5.75 billion.

Meanwhile, Postabon struggled to find traction. Hundreds of competing deal sites had popped up seemingly overnight.

Original Postabon investor Jason Calacanis explains the pivot.

- Realizing everyone had deal fatigue, and an inbox full of unused Groupons, Stu did what great entrepreneurs do when their first idea fails: he started over. He talked to all the local businesses he was working with and he found a real pain point: they had no tools to update their profiles on Yelp, Yahoo Local, Google Local, and dozens of other local sites.

Today Postabon is Signpost, a fast-growing company that helps small- to medium-sized businesses market themselves online.

Calacanis (investor in the first round of Uber and other notable companies) just invested in Signpost’s $20 million series C round of funding this May. Almost five years after his first investment.

Sometimes startup pivots work out.

Overnight successes are rare, as they should be. It usually takes a while to get somewhere meaningful.

Choose Again

Choosing to pivot isn’t good or bad. Like everything else, it depends on the situation.

You’re starting with a non-ideal scenario. Money has been spent on a project that’s likely DOA. Investors will be asking what’s next.

None of the choices are great. But scrappy founders have shown it’s possible to choose a different path and win big. Notable business pivots include Nintendo (various industries), Flickr (online gaming) and Instagram (check-in app), among countless others.

My primary takeaway is that pivots (and struggling startups in general) are full of lessons.

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned is this: here is where investors can add value. When a young company needs it most. Encouraging feedback, helpful critique, advice, ideas, capital, introductions. Just asking how you can help can provide a morale boost by itself.

Being able to add value to an investment is one of many neat things about this space. You’re investing in a team, not a ticker symbol. And the companies are early enough that your help can mean something. The best founders are responsive and open to feedback. They want to talk, hear ideas and practice their own pitch. In fact, if they’re not responding to investor queries (and feedback), I consider it a negative signal.

It feels organic. For me, it’s the opposite of “making a trade” (more on that here). It’s real investing.

Stay tuned,

Adam Sharp