The Tesla Stock Split Experiment

Abstract

On August 11, 2019 at 16:59 EDT, Tesla (TSLA) announced a 5-for-1 stock split. The trading in the after market and during the subsequent two days amounts to a unique financial economic experiment. Although stock splits have no fundamental impact on value, Tesla’s stock price rose 17.94% in the two days following the split – adding almost $50 billion in market value. This paper examines that price increase in detail and concludes there is no rational explanation for the size of the run-up following Tesla’s stock split announcement.

Introduction

Empirical financial economists are stuck between a rock and a hard place. To begin, we cannot do controlled experiments. We are not in a position to alter corporate policies or change market trading rules. As a result, virtually all our empirical work is based on statistical analysis of market data. Unfortunately, reliance on ex-post data opens the door to problems associated with measurement error, data mining, and nonstationarity. Even in those cases where highly significant statistical relations are found it can be hard to separate causation from correlation. In addition, there is a related problem that occurs when there are large short-term movements in a company’s stock price. The question that arises is whether the change in price, which can be measured with precision, was caused by a corresponding change in fundamental value or was the result of behavioral effects that led price and value to diverge. Robert Shiller was awarded the Nobel Prize in large part for his work which suggested that price typically moves more than value, but work in this vein remains controversial because of the difficulty of measuring changes in value.

There are, however, unique circumstances in which events conspire to produce something akin to a controlled experiment. Such instances are worth studying in their own right, even if it is difficult to draw broad conclusions from individual events. The particular “experiment” analyzed here was made possible by Elon Musk. On August 11, after the market close, Tesla announced that the company would be splitting its stock 5-for-1. As will become clear shortly, the announcement was unanticipated. The fact that the announcement was a split is particularly fortuitous. Since the path breaking work of Fama, Fisher, Jensen and Roll (1969), which introduced the event study technology, it has been known that stock splits, in and of themselves, convey no fundamental economic information and, thereby, should have no impact on value. Splitting a stock simply changes the unit of account. Share numbers rise and all per share magnitudes fall by the same fraction. It is possible, of course, that the split serves as some type of signal, more on that below, but the change in the unit of account itself has no real economic effect and, therefore, should not impact a company’s market value. Consistent with the theory, FFJR found that although stock prices ran up prior to splits, residual returns following the split were essentially zero on average. Subsequent research such as Huang, Liano, and Pan (2009, 2015), among others, produced basically similar results.

Tesla, however, proved to be an exception. As soon as Mr. Musk made the announcement the stock price jumped more than 6% in the after market. The following day, on the basis of no apparent news with respect to fundamentals, the stock price went on a wild ride before closing up 13.12%. But that was not enough, the next day, despite some oscillations, it ended up another 4.26%. Over the two days the total return was 17.94%. A small portion of this run-up can be attributed to the market. The Nasdaq index rose a total of 2.40% over the two days, although a portion of that rise was due to Tesla. What is particularly remarkable about the run-up associated with the stock split is that Tesla was a large market capitalization company at the outset. Prior to the split, the market capitalization of Tesla was $256 billion making it the sixteenth largest company in the United States by that measure. In the two-day run-up the market cap rose by $46 billion to $302 billion.[1] To provide perspective, the increase in Tesla’s valuation over the two days exceeded General Motor’s market capitalization of $39.4 billion. Of course, it is possible that the run-up was due to fundamental information released concurrently with the split, but as documented below that is not the case. All of this makes the Tesla run-up following the split announcement a story worth pursuing. In that respect, the next section analyzes the run-up in detail. The following section examines whether news other than the split can explain the run-up. It also analyzes other possible explanations for the price increase. The final section discusses implications of the results and summarizes.

[1] Calculations are based on 186.36 million shares outstanding.

The run-up

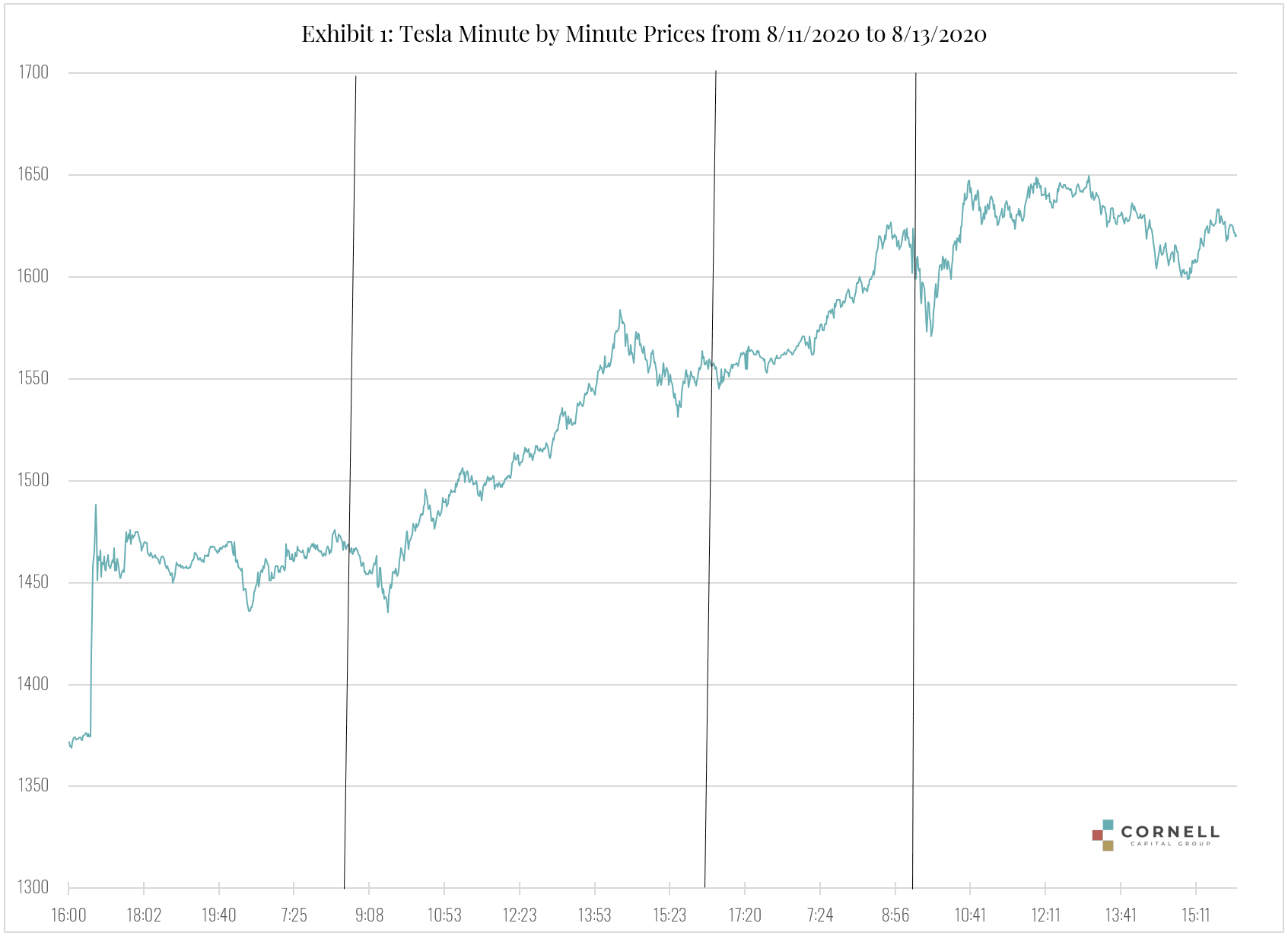

The story begins on August 11, 2020 at 16:59 Eastern Daylight time (all times in this paper are EDT) when Tesla announced via a press release that, “the Board of Directors has approved and declared a five-for-one split of Tesla’s common stock in the form of a stock dividend to make stock ownership more accessible to employees and investors. Each stockholder of record on August 21, 2020 will receive a dividend of four additional shares of common stock for each then-held share, to be distributed after close of trading on August 28, 2020. Trading will begin on a stock split-adjusted basis on August 31, 2020.” The reaction to the announcement in the after-market was immediate. It is seen clearly in Exhibit 1 which plots the minute-to-minute price of Tesla using data provided by Yahoo. The last trade prior to the announcement was at a price of $1,374.39. By 17:02, the price had jumped more than $100 to 1,476.04 an increase of 7.40%. Although the price continued to vibrate during the remainder of the after-market trading and during the pre-market trading the next morning, there was little net change. The last price before the market opening on August 12, 2020 was $1,459.00. (Opening and closing of the market are shown by the black lines in the exhibit.)

When the market opened on August 12, the price began to drop. To those steeped in market rationality this would not have been surprising. Theory predicts that if there is no confounding news, and if the announcement could not be interpreted as a signal, the split should have at most a minor impact on stock price. In an efficient market, therefore, the post-split price should be close the pre-split price. Consistent with that interpretation, by 9:45 the stock price was down to 1,435.50. From that point, however, the general direction was up sharply. By the close of trading, the stock price had risen to $1,554.76 up $180.13 or 13.12% from the close on August 11.

After the market closed on August 12, the price continued to rise in the after market. By the time the market opened the next day, it was up over $68.00 from the previous day’s close. When trading started on August 13, the pattern of August 12 was repeated although in a muted form. At the start of trading the price fell only to recover and reach new highs. By the close of trading, the price was $1,621 up another $66.24 or 4.26%. Over the two-day period the stock price rose $246.37 or 17.94%. As noted above, during the same time period the Nasdaq composite rose 2.40% so that the net of market return (including the impact of Tesla on the index) was 15.54%. Although beyond a horizon of two days it becomes difficult to continue to attribute movements in Tesla’s stock price to the split announcement, it is worth noting that in the following two trading days the stock continued up. On August 14 and August 17, Tesla rose 1.83% and 11.16% respectively, whereas the Nasdaq index fell 0.21% and then rose 0.57%. Over the full four days, Tesla rose 33.51% and the Nasdaq rose 2.78% so that the residual return was 30.74%. In total the stock price of Tesla rose $460.61 and the company added $85.8 billion in market capitalization. Only Toyota, among auto manufacturers, has a market capitalization measurably in excess of the increase in Tesla’s market cap and VW is close at $87 billion. Ironically, it is also well above Tesla’s March18 market cap of $65.8.

Although a residual returns of 15.54% are unusual, and a residual of 30.74% is extraordinary, particularly for large market cap companies like Tesla, it is not unprecedented. For instance, movements of that magnitude are observed in response to markedly unexpected earnings announcements. This raises the question of whether there was some confounding information, released along with the split announcement, that could potentially explain the dramatic increase in the market value of Tesla’s stock.

Confounding news and other explanations for the run-up

Like The Hound of the Baskervilles, the most salient characteristic of confounding news during the two days following the split announcement is that there wasn’t any. A careful check of the news wires did not reveal any information release by the company other than announcement of the split. In particular, there was no fundamental news related to the company’s financial performance or the production and sale of its products. Even Elon Musk was remarkable quiet during the interval. There were no controversial tweets or provocative comments. The only “news” regarding Tesla was the ongoing internet chatter, but that is a constant feature of the company. The same conclusion largely holds for August 14 and August 17, the two days following the two-day window plotted in Exhibit 1. Although there was continuing reporting regarding the stock split, fundamental was sparse. Elon Musk did comment over the weekend that Tesla was working an upgrade to its self-driving software. In addition, Wedbush upgraded the stock and increased its price target to $1,900 on August 17. Nonetheless most analyst ratings remained well below $1,500. Tipranks.com reports that the average price target was $1,295. In addition, the ratings and price targets tend to lag the stock price with analysts coming up with after-the-fact explanations for target price increases.

There were two additional components of the chatter that might be considered news. The first is the fact that in its announcement, Tesla said that the split would make the stock more accessible to its employees and investors, although it did not say what investors to which it was referring. That led to a lot of enthusiasm on Twitter and message boards regarding potential new buyers of Tesla stock. The problem with the “added access” interpretation is that the set of potential new investors must be small indeed. Most investors interesting in owning Tesla can afford the price of at least one share. Clearly this is true of all institutional investors. Furthermore, advances in electronic trading make fractional share ownership easy. For instance, virtually all major brokerages have automatic dividend reinvestment programs that involve the purchase of fractional shares. All this implies that added accessibility could not have more than a minimal impact on share value. Furthermore, if it did then presumably Amazon and Google, two of the world’s most sophisticated companies, would have split their shares long ago.

Another ongoing story commonly used to explain the recent rise in Tesla stock is the company’s potential inclusion in the S&P 500 index the following four straight quarters of accounting profits. Furthermore, there is a large literature that documents the fact that inclusion in the index is associated permanent increases in stock price.[3] The usual explanation for the run-up on announcement is that there will be added demand for the stock from passive investment funds. There two problems with applying this explanation this explanation to Tesla’s post-split run-up. The first and most important is that there was no new news regarding inclusion during the two days following the split announcement. The S&P story had been widely reported since the Tesla earnings announcement on July 22 made the company eligible. Second, the run-up is too big, particularly in dollar terms. The announcement effects reported by See Bennett, Stulz, and Wang (2020) are no more than 3% to 3.5% and in the later part of their sample they disappear altogether. Furthermore, the companies added generally have much lower market capitalizations than Tesla. Finally, the S&P 500 is a value weighted index so that the split itself, apart from any run-up it causes, should not affect the size of a percentage price increase associated with the inclusion of Tesla in the index. There is no theoretical connection between inclusion in the index and the stock price response to the split announcement.

Another possibility is that split could be a signal that management believes there are good times ahead. From the standpoint of economic theory, however, there is a problem with this explanation. For an announcement to be a signal, there must be a cost associated with signaling. As originally explained by Spence (1973), a signal can be a source of reliable information only if the cost of signaling is less for high quality companies than for lower quality companies. It is this difference in cost that leads to a viable signaling equilibrium. It is also the reason that stock splits cannot be interpreted as signals. Any firm in good standing can split its stock by following a standard procedure just as Tesla did. If the signal were expected to create value, any firm could signal. Furthermore, if splitting shares had a meaningful impact on value, then all major firms would split their shares at approximately the same price. That is not what is observed. Some major companies like Apple have split their shares several times while others, like Amazon and Berkshire Hathaway, have never had a stock split. Finally, given all the other information about Tesla in the marketplace, it is hard to imagine what new information the hypothetical signal could be providing.

The internet chatter does hint at one other issue worth investigating. A common refrain is that the split was a going to be boon and investors needed to get on board quickly because the stock was going to be driven to new highs. This momentum type argument suggests that perhaps during the two-day window minute-to-minute returns on Tesla stock would be positively correlated. It has been known since the early work of Roll (1984) that bid-ask bounce tends to produce a slight negative serial correlation in price changes, so the momentum effect would first have to overcome this. Here the serial correlation is estimated by running a simple regression of the current percentage price change on lagged price changes with the lag extending to 10 minutes so that there are 10 explanatory variables. August 12 and August 13 are estimated separately because it is possible that the momentum effect only occurred on the first day when the price increase was much more pronounced.

The results show no evidence of serial correlation. For August 12, none of the ten lagged price changes are significant. In addition, five of the coefficients are positive and five are negative. For August 13, the results are basically similar. There are two significant coefficients. At lag seven the coefficient is significantly positive and at lag ten it is significantly negative. This is almost certainly due to random chance. There is no ex-ante reason for significant coefficients at those lags or for the positive and negative sign. In addition, when estimating twenty coefficients one or two are expected to be significant. It is also worth noting that on both days the coefficient for lag one, presumably the most important explanatory variable, is essentially zero on both days. In short, there is no evidence of a short-term momentum effect in the minute-by-minute trading data.

Summary and implications

Putting all the pieces together, there is no rational explanation for the residual run-up in the price of Tesla shares in the two-day window following the earnings announcement. Elon Musk was able to create nearly $50 billion in value without making any new investment or altering any operations. It is hard to imagine any explanation that is not behavioral for the data presented here. Behavioral finance scholars can thank Elon Musk for doing an experiment that supports their research.

There are no doubt many behavioral explanations that can be offered to explain the results but that is left for future research. However, the Tesla stock split experiment does bring to mind a famous passage from Keynes (1936). Referring to investors, Keynes said, “For most of these persons are, in fact, largely concerned, not with making superior long-term forecasts of the probable yield of an investment over its whole life, but with foreseeing changes in the conventional basis of valuation a short time ahead of the general public. They are concerned, not with what an investment is really worth to a man who buys it “for keeps,” but with what the market will value it at, under the influence of mass psychology, three months or a year hence. Moreover, this behavior is not the outcome of a wrong-headed propensity. For it is not sensible to pay 25 for an investment of which you believe the prospective yield to justify a value of 30, if you also believe that the market will value it at 20 three months hence. Investors who concluded that the split would lead to a short-term run-up along the lines suggested by Keynes were richly rewarded. Those who assumed that rationality would ensue would have sold the stock during the decline following the market opening on August 12. That would have been a costly decision. Overall, the data presented here imply that reaction of Tesla’s stock price to the split announcement is a clear example of the change in price exceeding the change in value by a significant margin. If that conclusion is close to correct the implications are more than academic. It is also implies that the market is not sending proper price signals, at least in the case of Tesla, which has implications for the allocation of resources.

References

Bennett, Benjamin, Rene M. Stulz, and Zexi Wang, 2020, Does joining the S&P 500 hurt firms, http://papers.nber.org/tmp/75403-w27593.pdf.

Fama, Eugene F., Lawrence Fisher, Michael C. Jensen, and Richard Roll, 1969, The adjustment of stock prices to new information, International Economic Review, 10, 1-21.

Huang, G. C., Liano, K., and Pan, M. S. (2009) The information content of stock splits, Journal of Empirical Finance, 16, 557-567.

Huang, G. C., Liano, K., and Pan, M. S. (2015) The effects of stock splits on stock liquidity, Journal of Economics and Finance, 39, 119-135.

Keynes, John M., 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Harcourt, Brace, New York.

Roll, Richard, 1984, A simple implicit measure of the effective bid-ask spread in an efficient market, Journal of Finance, 39, 4, 1127-1139.

Shiller, Robert S., 1981, Do stock prices move too much to by justified by subsequent changes in dividends, American Economic Review, 71, 3, 421-436.

Spence, Michael, 1973, Job market signaling, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87, 3, 355-374.

[1] Shiller’s most famous paper in this regard is Shiller (1981).

[2] Calculations are based on 186.36 million shares outstanding.

[3] See Bennett, Stulz, and Wang (2020) for a recent contribution and the associated bibliography. Ironically, the authors find that in the long run inclusion in the index is associated with negative residual returns.

DISCLAIMER: CORNELL CAPITAL GROUP LLC IS A REGISTERED INVESTMENT ADVISER. INFORMATION PRESENTED IS FOR EDUCATONAL PURPOSES ONLY AND DOES NOT INTEND TO MAKE AN OFFER OR SOLICITATION FOR THE SALE ...

more