Why Regulators Might Welcome A T-Mobile US – Sprint Merger

In light of the recent news around renewed merger talks between T-Mobile US (TMUS) and Sprint (S), we have read a lot of discussion about the regulatory risk in such a transaction. It seems that a majority of observers believe a deal will be hard to get done.At first blush this is understandable. After all, regulators blocked the 2011 merger attempt between AT&T and T-Mobile US and the 2014 merger attempt between T-Mobile US and Sprint, both times for the same reason. They wanted to preserve the status quo of four national competitors rather than see a decline to three national competitors.

There was a time when there was a sound industrial logic behind these regulator objections. Reducing four competitors to three might have led to price increases and hurt consumers if it had happened 10 years ago. We believe, however, that the facts today no longer support these objections. Below, we will identify four structural changes in the wireless industry that have substantially increased competition in recent years. We note that a lot of these changes came into full effect after regulators rebuffed T-Mobile US and Sprint’s previous merger attempt, and are still ongoing today.

In our view the facts suggest that the US wireless industry would be more competitive with three national players today than it was with four national players as recently as five years ago. Moreover, as we will discuss below, it seems unlikely that consumer prices will increase as a result of this merger. So in the spirit of John Maynard Keynes, “when the facts change, regulators should change their mind.”

We go one step further, and argue that a T-Mobile US – Sprint merger has the potential to deliver significant benefits to consumers by increasing competition in several adjacent markets, specifically in the pay television and broadband internet markets. Unlike wireless services pricing, which has been in a steep and accelerating decline in the last decade, pricing for traditional television bundles has increased faster than the overall rate of CPI inflation. And on the broadband internet side, many households in America today have only one or two options for broadband internet access. We explain why a merged T-Mobile US – Sprint would be in a superior position to disrupt these less competitive markets, and ultimately lower prices for consumers.

Thus, while we do not believe meaningful consumer negatives are likely in the wireless market, we see the potential for significant consumer benefits in the pay television and broadband internet markets. The lines between internet access services (of all kinds), telephony services, and media / content services have been blurring for some time, and there is a distinct trend towards converged offerings of all of these services. When viewed in the context of a broader market definition encompassing all these services, we believe it is difficult to escape the conclusion that a merger between T-Mobile US and Sprint will increase competition and benefit consumers.

In other words, when viewed in a more appropriate, broader context, regulators might welcome a deal, rather than block it.

Structural Changes in the US Wireless Market

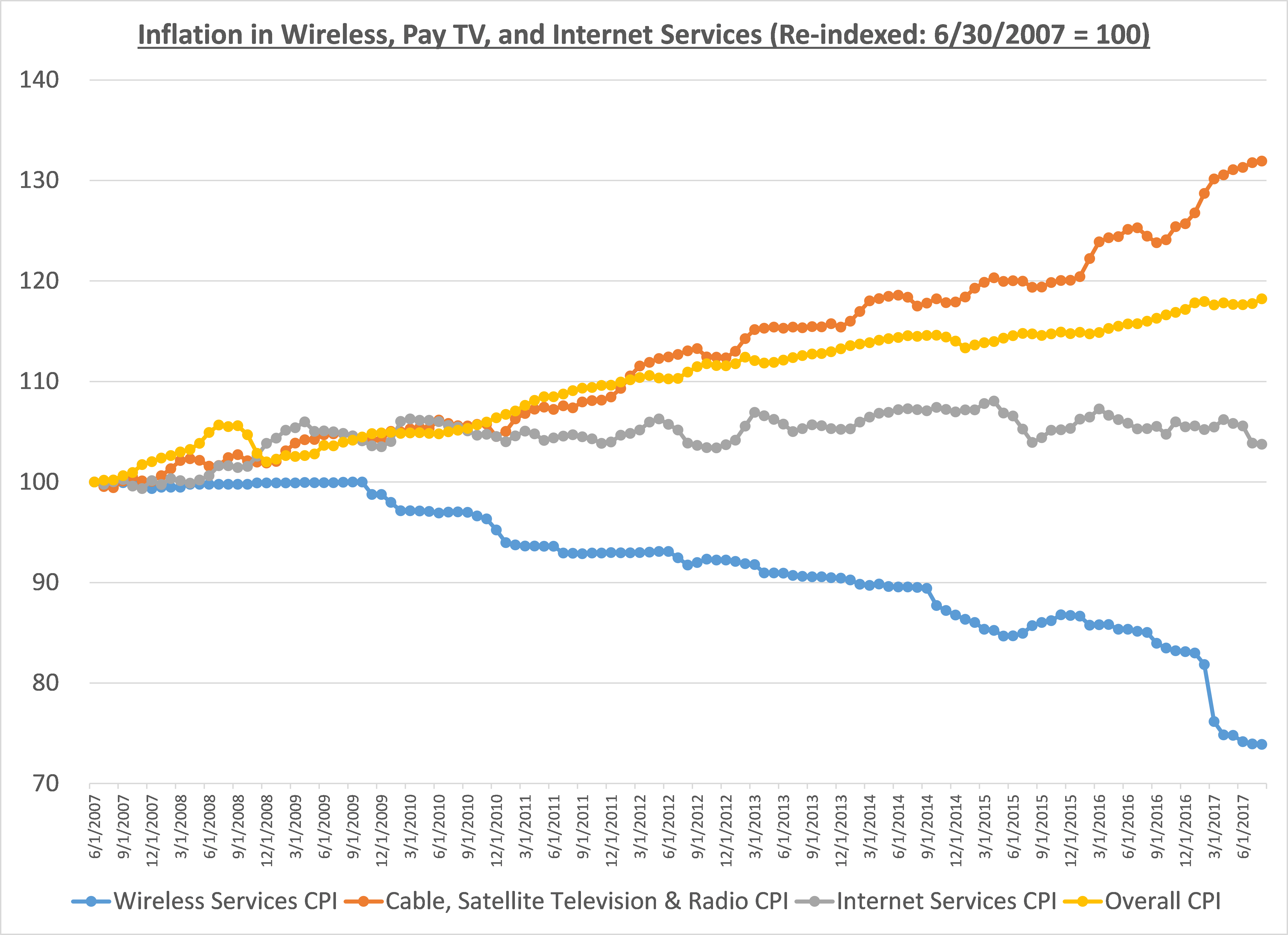

We begin with a high level view of historical CPI inflation in the US wireless market compared to the overall CPI and the CPI for pay television and internet services. We begin the comparison in June 2007, when Apple introduced the original iPhone, marking, in our view, the beginning of the modern wireless era.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Several points stand out. First off, wireless services are the only category for which prices have actually declined in the last decade.In fact the decline has been a rather substantial 26%. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, there has been a marked acceleration in price declines recently. The recent declines have been so rapid that the Federal Reserve called them out repeatedly as a reason for overall inflation missing their targets, for instance in the minutes of the June FOMC meeting.

We believe that this acceleration in price declines is not an accident, but rather the result of at least four powerful structural changes in the US wireless business in the last decade:

- The end of iPhone exclusivity

- Convergence in network quality

- The end of two year contracts

- The rise in unlimited plans

The first two points are particularly powerful, but do not take it from us, take it from Craig Moffett, the star analyst and founding partner of MoffettNathanson, who explained them very clearly in a recent interview with Bloomberg.

Simply put, it used to be that the different wireless providers in the US were not really perfect substitutes for one another. AT&T (T) carried the iPhone exclusively from 2007 to 2010, and Verizon (VZ) long had the well-deserved reputation of having the best network. If you were a die-hard Apple fan, you had to be with AT&T.If you wanted the best network, you had to be with Verizon. The only reason to go with either T-Mobile or Sprint was to get a lower price.And to get that lower price, many customers would have had to accept far inferior service, as network quality at T-Mobile or Sprint used to be far worse than Verizon or AT&T. To many of the industry’s best customers, it was an unacceptable trade-off, almost irrespective of price.

As a result, AT&T and Verizon largely split the industry’s best customers between them. Even though there were technically four national wireless competitors, the effective number of competitors for the best customers was really one or two. This is why we think it is fair to characterize the US wireless market between 2007 and 2010 as an effective duopoly.Ironically, even this rather cozy duopoly structure did not result in an increase in pricing, with the wireless services CPI flat to declining.

This industry structure first started to erode on February 10, 2011, when Verizon launched the iPhone. We do not think it is an accident that the first significant decline in wireless pricing (outside the financial crisis) occurred in late 2010, in preparation for the end of AT&T’s iPhone exclusivity.After all, AT&T had a tremendous incentive to lock in iPhone customers ahead of new competition from Verizon.

Sprint followed suit and launched the iPhone on October 14, 2011. Stunningly, it took T-Mobile until April 12, 2013 to offer the iPhone, apparently because Apple considered T-Mobile’s network too inferior prior to the rollout of LTE, as T-Mobile US CEO John Legere explained at Deutsche Telekom’s 2015 capital markets day:

“[At the time of the previous capital markets day on December 6, 2012] We were number four in J.D. Powers for sales and care and the reason we were at a whopping fourth is there were only four. Otherwise, we would have been a little bit lower.

We had an amount of LTE in our network of zero and we were hoping to get the iPhone and all of a sudden Apple demanded that we have LTE”

This comment also highlights the stunning turnaround in T-Mobile’s network quality.Less than five years ago, Apple apparently considered it too inferior to carry the iPhone. Today, T-Mobile’s coverage is almost on par with Verizon, and T-Mobile is widely recognized as the fastest wireless network in the US.In fact, for a large fraction of the US population, T-Mobile is objectively the best network available today, and the differences between AT&T, Verizon and T-Mobile are small enough that all are legitimate substitutes for one another from a network perspective.

Thus even if Sprint disappeared off the face of the earth tomorrow, the other three carriers are more effective competitors today than the four carriers were as recently as 2013 (and certainly in the duopoly days of 2010), because of effective parity in their network and phone offerings.We believe that this is a large part of the reason that price declines in US wireless accelerated in recent years.

More importantly from regulators’ perspective, if you reduced the number of competitors from four to three today, we believe the industry would almost certainly remain more competitive than it was in 2007 – 2012, a period where wireless pricing declined on an absolute basis, even while overall CPI was rising.So when we hear people state that a T-Mobile – Sprint merger would lead to higher prices for consumers, we wonder how they reach that conclusion.

But the pace of change in the wireless industry did not stop after 2013. We see at least two additional changes in the industry structure that further contribute to increased competitiveness.

The more important one is the end of two year contracts, which began with the launch of T-Mobile’s Uncarrier strategy on March 26, 2013.For those who followed the wireless industry back in the dark ages of 2003, you will remember that two year contracts were then the industry’s ingenious answer to FCC-mandated number portability. Recall that prior to November 2003 you could not take your phone number with you when switching carriers, providing a huge barrier to switching.So operators introduced two year contracts as a new way to lock in customers and reduce churn.

Predictably, the industry initially resisted the Uncarrier move, given the possible increases in churn and overall competitiveness.In fact, when regulators reportedly dissuaded T-Mobile and Sprint from merging in 2014, none of the other carriers had followed suit.But this began to change on August 13, 2015, when Verizon announced the end of two year contracts. AT&T and Sprint finally ended contracts on January 8, 2016.

It should be clear that this is a step change higher for competition in the wireless industry.Previously, when one competitor had a superior offer, many customers were unable to take advantage because they were locked into a long-term contract with an existing provider.And as a result it should be unsurprising that the largest pricing declines on record occurred after the end of two year contracts. More importantly, it suggests that future price increases are even less likely than based on our initial argument of phone and network parity alone.

The final and most recent industry change occurred this year with the move to unlimited plans, which was again driven by T-Mobile. The reason this matters is that it makes the different carriers’ service plans even more interchangeable. While carriers previously segmented their customer bases with different rate plans, it has now become easier for consumers to make an apples-to-apples comparison between different carriers. Greater transparency in pricing should further increase competitiveness, and has already allowed millions of consumers to benefit from lower pricing compared to the previous bucketed data plans. To be clear, we do not expect the huge price declines from early 2017 to repeat, but we believe unlimited plans make it even harder for wireless companies to raise prices in the future.

In summary, we believe that the US wireless industry structure is the most competitive ever today. Moreover we believe it would remain more competitive than in the 2007 – 2012 period of declining wireless prices even if the number of competitors went from four to three as a result of a merger between T-Mobile and Sprint.

So we strongly agree with the FCC’s conclusion this week that there is effective competition in the mobile wireless industry, and with FCC Chairman Ajit Pai’s statement that “most reasonable people see a fiercely competitive marketplace.”

Increasing Competition in Adjacent Markets

The previous section discussed why we do not believe that consumers will be harmed by a merger of T-Mobile and Sprint. In this section we will highlight why consumers could actually benefit from increased competition in adjacent markets, in particular the pay TV and broadband internet markets.

Pay TV is a fascinating market that is undergoing a tremendous amount of change as we speak. Cord cutting, the emergence of over-the-top streaming platforms, and the sustainability of the traditional linear cable TV bundle are frequent and important topics of discussion.We believe that the root cause of this disruption lies in the inflation chart we showed earlier in this article. Pay television bundles have experienced significantly greater price inflation than other telecom and media services, making them expensive, particularly compared to many emerging alternatives.

Think of the value of a Netflix (NFLX ) subscription at $10 / month compared to the cost of a traditional cable bundle, especially for a household that is not interested in sports programming. But in a great example of the disruption that T-Mobile has already brought to this market, T-Mobile customers now get Netflix free.Similarly Amazon Prime customers receive free Prime video, and there is abundant free video content available on online platforms lead by Youtube and Facebook.

Obviously, this price discrepancy is making the traditional cable bundle vulnerable to disruption, and the way people consume and pay for video content is changing. Most likely people will continue to consume ever-increasing amounts of video content, and we believe that they are willing to pay for things they like.But the days of paying significant amounts for content you do not watch will likely come to an end sooner rather than later.Consumers are looking for new, cheaper choices.

It is difficult to impossible to predict exactly how this will play out in the coming years, but we are confident in that the critical disruptors in this ecosystem will share two characteristics – scale and the absence of a legacy business that would be wrecked by disruption.Both of these suggest strongly that a merged T-Mobile – Sprint would be an important disruptor in the pay TV business in the future, with “Netflix on Us” representing just the tip of the iceberg.

To understand why scale and the absence of a legacy business matter, consider Netflix. Netflix has changed the game in the content business by being willing to spend multiples of its media competitors’ content budget to deliver a service with scale. It is the perfect “flywheel” – more content attracts more customers, revenue from whom drives further increases in content investment. So clearly scale matters.Buy why, you may ask, did none of the traditional media companies follow this play book? We believe the answer is simple – they make too much money from the status quo of the cable TV bundle. This is not necessarily a criticism of the media CEO’s.Ask yourself this – would their shareholders tolerate foregoing profits and dividends derived from their existing businesses to pursue increased investment and a new business strategy? Disruption is far easier when you are disrupting someone else’s business than your own.

These same arguments suggest that a combined T-Mobile – Sprint could be a prime disruptor on the distribution side. With no existing TV business to protect, the combined company would be in a superior position to deliver new choices to consumers, building on “Netflix on Us.”And with the increasing scale of the combined company, they would be large enough to do transformative deals with content owners. After all, the combined company would have many more subscribers than even the largest video distributors today.While T-Mobile is likely to pursue this strategy on its own, there is no doubt that the increased scale resulting from a merger has the potential to significantly enhance the company’s position and accelerate disruption for the benefit of consumers.

The broadband internet market is a longer-term, but potentially even more interesting and disruptive story. Most may not realize that T-Mobile is actually in this market already today, albeit in a tiny way. Subscribers to the company’s most expensive rate plan T-Mobile ONE Plus International, which costs an additional $25 / month / line, offers unlimited 4G LTE mobile hotspot data.So conceivably, a subscriber could “cut the cord” of traditional wired broadband today and receive all their internet service over a T-Mobile LTE hotspot for only $25 / month.

Of course, few people would actually want to do so currently.Wired broadband via cable or fiber is a superior service today, due to its greater speed and reliability. That could change in a few years, however, when the US wireless industry converts to 5G, which by all accounts will represent a transformational change in wireless network capacity. In fact, Verizon has already made it clear that they view 5G, not fiber to the home, as the preferred last mile solution for broadband in the future.Lowell McAdam, Verizon’s CEO, discussed this earlier this month at Goldman Sachs’s Communacopia conference with analyst Brett Feldman:

Lowell McAdam

we've been investing for years in 3G technology and Fios buildout and we're now repurposing those dollars to 5G technology and fiber buildout but it's a different architecture than what we've done before.

[…]

Well, I think that's where 5G and over-the-top come in because even in the markets where we have our files footprint from Washington to Boston, the preferred method, the preferred architecture for us is going to be that last mile being 5G.

[…]

Brett Feldman

So if we think about that strategy to potentially take 5G as a residential broadband service anywhere in the country, you're comfortable taking that as a standalone service and if they want video, you have it but you're not necessarily doing this because of bundling?

Lowell McAdam

Yes, absolutely.

So what he appears to be saying is that 5G will offer sufficient capacity to deliver broadband to customers’ homes.Rather than have expensive truck rolls to install fiber in customers’ homes one by one (the old FIOS way), he apparently intends to run fiber to the neighborhood to support a dense 5G network and mail customers a 5G router.

If 5G is able to deliver on that promise, this solution could be an order of magnitude cheaper than existing cable or fiber solutions, both on a capex and on an opex basis (no more service calls and technicians running wires in customers’ homes). And he is in a position to know more about the technology and the economics of both alternatives than almost anyone else.After all, Verizon connected fiber to millions of homes for its FIOS service, still runs the largest wireless network in the US, and is probably the single largest owner of fiber backhaul systems in the world.

The consequences for the incumbent broadband players could be nothing short of earth shattering.Most consumers today can only buy wireline broadband internet access from one or two companies. Suddenly, wireless companies with sufficient spectrum and a dense enough network could compete with an offering of comparable speed and reliability to wireline broadband.

But spectrum and network density are obviously the crux of the issue, as they are the two biggest constraints on wireless companies’ ability to provide comparably fast, reliable service. In-home data consumption can be orders of magnitude higher than data consumption on a cell phone (think of all the devices on your home Wi-Fi network, streaming in 4K to multiple TVs, …), so it will require orders of magnitude greater network capacity and investment than today’s wireless networks. Verizon’s solution appears to be deploying the millimeter wave spectrum acquired from Straight Path, combined with an unprecedented investment in fiber, including a purchase commitment to Corning to “buy enough fiber to string to Mars.”

On their own, we find it difficult to believe that either T-Mobile or Sprint would have the spectrum or the capital resources to compete in this business at scale. But combined, they would own a larger position in low and mid band spectrum than AT&T and Verizon put together. Moreover they would have the scale and cash flows required for an investment in a densified 5G network.

So we believe that allowing a merger between T-Mobile and Sprint could create a formidable new competitor in the broadband internet market in the next decade. Suddenly broadband internet could go from having one or two competitors in a typical home to having three or four (with the addition of Verizon and a merged T-Mobile – Sprint).

We conclude this section by reiterating why we see a combined T-Mobile – Sprint as the prime potential disruptor in both aforementioned markets.The combined company would be the only one in the competitive set with no incumbent TV or broadband business to protect (unlike all other cable, satellite, and telecom companies). When you have no existing cash flows to lose, it is easy to do the disruptive things that benefit customers but might otherwise wreck your existing business. This aligns T-Mobile’s interests uniquely with consumers, because delighting consumers allows them to take share from competitors, and drive pure revenue and cash flow upside.

Moreover, T-Mobile has already built a significant track record of disruption with 14 Uncarrier moves and counting. And the company has done so while delivering strong growth in revenues and cash flows, even while being the primary driver of significantly lower prices for consumers in the wireless business.

Ask yourself this – which of the following seems more likely following a potential T-Mobile – Sprint merger? That John Legere would suddenly turn around, abandon the highly successful Uncarrier strategy and raise prices on consumers, or that he would use the increased scale and synergies of the combined entity to further accelerate his Uncarrier strategy, delighting customers, and thereby take additional market share from incumbents?We think the answer is obviously and emphatically the latter.

Personally, even though we cannot predict exactly how all of this will unfold, we are excited to see the things that John Legere and team could deliver for both customers and shareholders armed with the increased scale resulting from a merger of T-Mobile and Sprint.

Disclosure: I am / we are long TMUS.

Disclaimer: None of our writings are intended as financial or any other advice. For financial advice, please consult your own advisors familiar with ...

more