Dividend Reinvestment Plan Real-Life Example

The compounding from dividends can be an incredible force. I have a dividend stock I’ve held and reinvested dividends in for over 5 years. I feel this stock is a great dividend reinvestment plan example especially to how it literally multiples your total return.

A dividend reinvestment plan, or DRIP, is one where any dividends received are automatically reinvested in that same stock.

It’s a fantastic plan because it’s:

- Automatic

- Habit forming

- A compounding effect

- Creates returns which multiply

I don’t use that “multiply” word lightly. It literally does multiply.

After all, that’s the power of compound interest. Compound interest is exponential, which means that returns multiply on themselves. A powerful force over a long enough period—I’ll show you exactly how with this dividend reinvestment plan example.

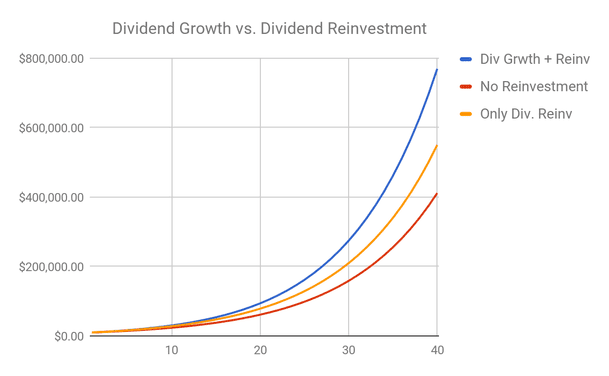

Before we dive into the exact company I purchased over 5 years ago and have used the DRIP with, check out this visualization to see the difference between a stock with reinvested dividends and one without:

You could repeat these simple charts yourself, as I’m using historical averages for the following:

- Annual return = 10%

- Dividend yield = 3.26%

And just for giggles, here’s if we assumed that the company grew its dividend 5% per year, adding a third layer of extra compounding:

These DRIP examples should be enough to seal the door on this topic altogether, but I know we all (myself included) want to see the real deal.

This one will just more simpler math, and I’ll be taking screenshots from my real brokerage account (the one I use for the Real Money Portfolio of The Sather Research eLetter).

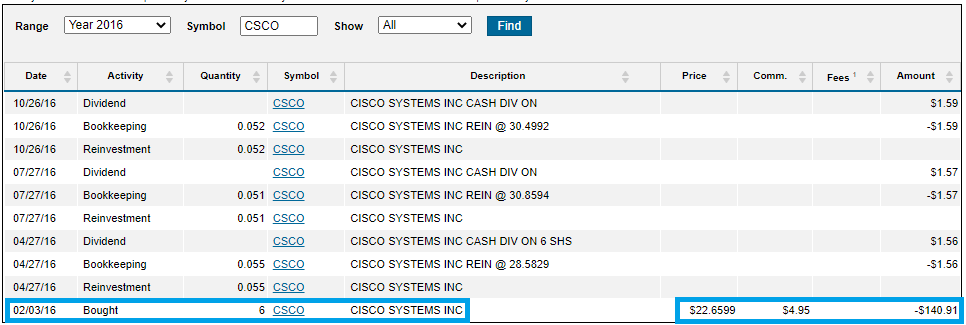

There’s this technology business which was trading at a fantastic valuation back in 2016 which I purchased: Cisco Systems (CSCO).

Here’s the buy order, and some dividends I received from it that year:

You can see that yes, this was in the old days back when you had to pay a small commission to buy and sell stocks. Buying fractions of shares wasn’t even heard of.

Also notice how small those initial dividends were, more on this later…

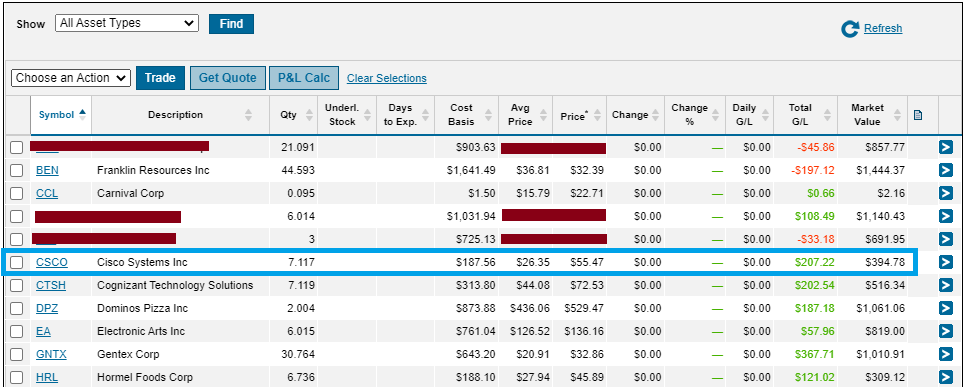

Now, let’s get an update on the position as of today. I want to emphasis I did not make any additional purchases of the company since, other than the shares from the dividend reinvestment plan.

(this is a screenshot for one of the brokerage accounts for the Real Money Portfolio).

Another weird quirk is that the “Total G/L” is different than my real gain/loss because Ally Invest adds dividend reinvestments to Cost Basis. I’d argue this should not be the case because my dividends are “free”; maybe it’s for tax purposes but this is a Roth IRA.

The bottom line is that I used $140.91 to buy 6 shares of Cisco in 2016, and did not buy any additional shares, and the dividend reinvestment plan has added an additional 1.117 shares. That’s basically 18.6% of my initial investment added strictly from DRIP.

Without DRIP, my return on 6 shares would be 110.5%. Not a bad return over 5 years, but significantly less than the 180.2% total return I have because of the dividend reinvestment plan (more on that calculation later).

Needless to say, these extra shares from the dividend reinvestment plan have been a great boost to total return.

You can also see that the stock now trades at $55.47. That means that the extra shares from DRIP alone are currently worth $61.96.

Just those extra shares are already worth almost half of my initial investment.

Another good example of the great things that can happen from DRIP in a good company that you hold for the long term. It’s not unreasonable to think that in another 5 years, the extra shares from a continuation of DRIP could be worth more than my initial investment itself—almost as if the investment I made was “free”.

How DRIP Makes Total Return Multiply (Example)

What I wanted to highlight for this dividend reinvestment plan example is how total return is multiplied from this factor.

First off, let’s calculate total return, as the current total value of the investment versus the initial value.

My Cisco shares are currently worth $394.78, and remember I paid $140.91, and so my total return over these 5 years is 180.2%.

Let’s say that Cisco’s stock were to jump +10% tomorrow. A lofty hope, but bear with me just for this example.

That would push the stock price from its current $55.47 to $61.02.

But my return would not add +10% from 180% to 190%. It would actually be much higher.

Using today’s current shares:

- 7.117 shares

- $61.02 price

- $434.28 total value

Now let’s compare our new total value versus the amount I paid initially ($140.91):

Total Return = ($434.28/$140.91) – 1

Total Return = 208.2%

You can see how total return jumped from 180.2% to 208.2% on a +10% jump of the stock.

That’s the power of compound interest, and DRIP! I hope it’s obvious now why I say how a good dividend reinvestment plan can cause return to multiply!

A Few Caveats on Total Return

Now, also understand that this knife cuts both ways. If the stock were to drop 10%, the total return would also drop by a factor greater than 10%.

But if you are interested in holding stocks for the long term, and you are confident that your companies will continue to grow even if they experience setbacks, then this drop would likely be temporary and your total return should continue to mushroom upwards in a compounding fashion.

Also keep in mind that if you are tracking your portfolio’s performance from month-to-month, you won’t see this multiplicative effect to total return.

This is because your portfolio has already factored the multiplied effect of dividend reinvestment each time you measure it. Over the long run, if you were calculating a final value from an initial value (what you put in), you would see the multiplicative effect. But as compounding dividends add multiplied value step-by-step, you don’t see a big multiplication because in each step its effect is being captured, since you’re comparing one month to the other rather than the final value from the initial.

Hope that makes sense.

Lessons from this Dividend Reinvestment Plan Example

The longer that you hold a stock, the greater the multiplicative effect you saw here today.

It really lends credence to the idea that there’s a huge advantage to the investor who can simply sit on their investments and wait for each to compound.

Since returns from DRIP multiply like this, it’s not unreasonable to think that what you consider a “losing position”—one that has underperformed for a long stretch of time—can quickly rebound and “catch up” through the power of compounding.

As you accumulate more and more dividends on a position, the Total Value of the position will swing higher and lower compared to the initial investment you put in. Meaning your Total Return will swing much higher and lower.

To see that on the upside will be a very powerful thing, and it’s simply due to the way Total Return is calculated and the effect of the dividend reinvestment plan.

That said, we can’t use this effect as an end-all, be-all excuse for blindly holding on to terrible investments.

The compounding effect of a stock that eventually goes bankrupt is zero.

And the opportunity cost from holding on to an underperforming position, especially if that money could’ve been “spent” somewhere else for much better compounding, is a real problem.

I think the best plan is to be somewhere in the middle of this idea, patient enough to let underperformance ride out for longer than you might think, but ruthless in identifying when a company’s fortunes have really changed for the worst (negative earnings or a dividend cut could qualify).

I know how tough it is to hold on to underperforming positions, especially because I’ve had a few over my (almost!) decade of investing.

I consistently track how the positions in my portfolio perform versus how the S&P 500 performs over the same time period. As the S&P 500 takes off, its Total Return tends to also mushroom as a 10% gain represents multiplied Total Returns (a similar but different multiplicative/compounding effect).

It leaves underperforming positions in the dust.

That said, there’s a few reasons that a company could make up that difference—and then some—if the investor is patient.

A few examples in the short time I’ve been investing which really rocket up the stock price of a company (catalysts):

1—When a company is acquired

This is a huge one because:

- Research has shown that companies overpay for acquisitions more times than not

- The stock price of a company about to be required generally rockets higher (10% or even 30%+ is possible) to reflect this “premium”

The reality of the stock market is that a stock’s endgame is really only two things: (1) bankruptcy and (2) being acquired.

You could also have spinoffs/ divestures, but I’ve seen research that around 10% of all companies have gone bankrupt, leaving a huge portion to either be acquired, merged, spunoff, or simply… continue to survive.

Sticking around long enough to eventually get acquired can be a great way to make up lost ground for a stock that has been underperforming, especially the more shares you’ve DRIPPed into it.

This is especially true for smaller companies, or big companies which get spunoff to smaller companies which are then acquired.

2—When a company makes a strategic change

If a stock has been depressed because investors perceive that the company is stuck to their old ways, or has historically been bad allocators of capital, then any change or signal of a change could cause the sentiment to change, which can do big things to the valuation. That’s classic value investing.

A company could have assets which were highly underutilized, or could have big piles of cash or marketable securities that they finally put to work which eventually create additional value for shareholders.

You could also see a company announce new initiatives for focusing the company’s efforts, such as the automakers and their newfound commitment to Electric Vehicles, or the oil majors who have talked about their new involvements in Green Energy.

Simple things like these can propel a stock to new valuation levels before the beneficial results of these decisions are reflected in the company’s true fundamentals at all.

3—When a company gets a great, new driver of growth

I’ve seen this personally in companies I’ve held such as Microsoft and American Eagle. In the case of Microsoft, it was the very first stock I ever purchased, which had been flat for over a decade (and I was blissfully unaware of).

At the time, Microsoft didn’t seem to have any avenues for future growth—that is, until their investments into the cloud (with Azure) took off and created a whole new world of opportunities for the company (check out their growth rate since 2017, truly astounding for a company of their size).

Once the company found new growth through Azure, and it eventually made its way into the financials through growth of revenues, and then Operating Income and Net Income, Wall Street came around to the fact that this was a new company and attached higher valuations to it, causing a massive rocketing higher in the price.

American Eagle was another example for me. Left for dead in a flat yoyo of peaks and valleys, the stock finally found some momentum after the pandemic from excitement around its developing Aerie brand.

Aerie was a growth driver for a little while, but it started out very small. After reaching a certain size Wall Street finally caught on, and it was a great investment for me to eventually sell on negative earnings, with my dividend reinvestments really multiplying the Total Return I received.

To summarize the catalysts, and maybe add a potential few:

- New strategic direction

- The “value unlocking” we’ve talked about already

- Recovery of the industry

- Changing secular factors

- Acquisition rumors or an acquisition

- Even, a spinoff leading to higher returns than the combined company could generate, especially if the sp un off company gets valued like a growth stock.

Final Thoughts

The power of a dividend reinvestment plan is really the power of compound interest disguised. But its multiplicative effect is real.

As you apply this to your investing decisions (or not), think about how it aligns with your goals.

For example is calculating Total Return important to you? Or is calculating incremental improvements in portfolio return more important (in which case you won’t see multiplication in the results of the formula)?

Is having a nice looking Total Return figure more important to you? Or is having the highest possible compound interest more important?

While it’s true that selling a stock interrupts compound interest and its effect on your Total Return numbers, it doesn’t really interrupt compound interest if you fully reinvest it into the market.

And so locking in gain where you’ve outperformed the market doesn’t really “interrupt” compound interest, as long as the after-tax effect still shows outperformance.

(On the flip side, locking in a gain just because it’s outperforming can be painful especially if the stock you sold continues its strong momentum, and the company continues compounding capital. Just because you think you’re right doesn’t mean you’re right, and the uncertainty of the market can make holding better than selling+buying probably most of the time).

There’s really no perfect answer here.

But I hope I’ve given you additional thought into the power of the dividend reinvestment plan, and some of its various implications to Total Return.

Just remember—the longer the holding period the greater the multiplicative effect of DRIP… that’s compound interest.

Disclosure: The author doesn't hold any securities that may be listed.