Common Investing Mistake: Income Obsession (& More)

Image Source: Pexels

Income Above All

A dividend investing strategy is usually aims to create an income stream from a portfolio, to live off dividends and keeping the capital comfortably secured in a brokerage account. If you hold your shares, you get your paycheck. It’s like a pension plan, by you manage it! However, a common investing mistake is income obsession.

Why you do this

Many investors choose high-yield stocks to increase their paycheck without taking “additional risks”. I appreciate the desire for additional dividend income but look at the big picture; the risks are real.

How it hurts your portfolio

Not all high-yield stocks are bad investments. However, exercise caution when selecting them because you need cover inflation long-term and avoid dividend cuts.

Inflation. Unless you’re 80 today, (skip this part if you are), you’ll have to generate income that covers inflation for 10, 20 or even 30 years. A high-income strategy is only valid if the dividend increases by at least 2% per year (currently, 2% doesn’t cover inflation, but over the long term, it does). If you cannot reasonably expect yearly 2% dividend increases from the stocks in your portfolio, there’s trouble ahead.

Dividend cuts. The absence of dividend growth is the first step toward a dividend cut. While the stock market went up and down a few times in the past decade, we haven’t a recession, yet. What will happen to stocks that failed to increase their dividends from 2017 to 2022, while interest rates were low and the economy was doing well, when we times get rough? Likely, a dividend cut. Therefore, it’s essential to monitor your holdings quarterly.

Most dividend cuts have a terrible effect on your portfolio. Not only do you lose income, but the share price usually takes a hit at the same time. Sadly, this happens a lot more during recessions. A positive note, you can “clean” your portfolio before this happens.

Fixing it

Buying high-yield stocks isn’t the problem. In fact, we’ve built two DSR retirement portfolio models (Canadian and U.S.) averaging between 4% and 5% yield. While I personally discard most stocks offering a yield over 6%, you can pick a few good companies in that range.

The key is to monitor their dividend growth, track their payout ratios carefully and, for DSR members, review their dividend safety score.

If the dividend hasn’t been increased in the past 18-24 months (or worse), go to their financial statement to see the payout ratio. Without solid expectations of dividend increases, seriously consider selling the stocks, regardless of their actual yield. Would you stay with an employer who has not given you raise for 4 consecutive years?

Yes, you might have to sell some of your “best income earners”. Still, you’re better off with a slightly lower yield but steady future dividend increases than a high yield getting eaten by inflation!

Holding Too Many Stocks

Starting to invest is like opening a bag of Doritos, you can never get enough! Do-it-yourself investors start with a decent number of holdings in their portfolio. As years pass, it’s tempting to add more. Holding too many stocks is a common investing mistake.

Why you do this

You like your existing positions, and you follow the buy and hold methodology that paves the way to magical dividend growth and impressive total returns. I always say, keep your winners as long as they fit your investment thesis.

However, as you create your list of potential replacement stocks, you find new opportunities. It makes sense to add a few stocks in those industries. But doing so year after year makes a portfolio with 70 stocks!

How it hurts your portfolio

Three problems with more than 40 stocks in a portfolio.

- Time. I review each of my holdings’ quarterly reports, their financial metrics (starting with the dividend triangle), and I verify that they raised their dividend in the past 12 months. Doing this for 35 positions takes time, imagine for 75+ stocks! This increases the risk of missing crucial information and putting your portfolio in jeopardy.

- Diworsification. This means adding holdings to a portfolio without improving diversification, for example, adding a 4th pharmaceutical company. Pick the best stocks for each industry instead of doubling exposure to an industry you already have. Also, 75 stocks in a portfolio looks a lot like an ETF. Why spend effort managing a portfolio that’s like a dividend growth ETF you can purchase within minutes?

- Portfolio weighting. When you buy a new stock, you want it to matter. If it represents 0.5% of your portfolio, how does it benefit you? Even if it doubles in price, it adds 0.50% of total return; you won’t feel it.

Fixing it

Adopt this rule: one in, one out! Identify the number of holdings you’re comfortable with having to follow quarterly. Want to add a new position? Review your portfolio; determine if you’re still holding only the best for each industry. If not, sell one position and add the new stock. Identify your holdings per sector to see if you have duplicates you can sell; if you have Pfizer (PFE), AbbVie (ABBV), and Merck (MRK), sell one to buy the stock you want.

Focusing on Valuation

Another common investing mistake is focusing too much on valuation makes you skip amazing companies for the sake of not paying too much for a stock. It’s particularly true for growth stocks.

For classic dividend payers with steady growth, you can use stock valuation methods to determine an appropriate entry point. However, I don’t understand sitting on the sidelines until a stock reaches a specific price.

Why you do this

Investing in January 2008 rather than March 2009 would’ve been ill-advised, so it’s easy to see why some investors look to valuations:

- Some stocks trade at such high valuations that you wonder how they’ll ever match the market’s expectations.

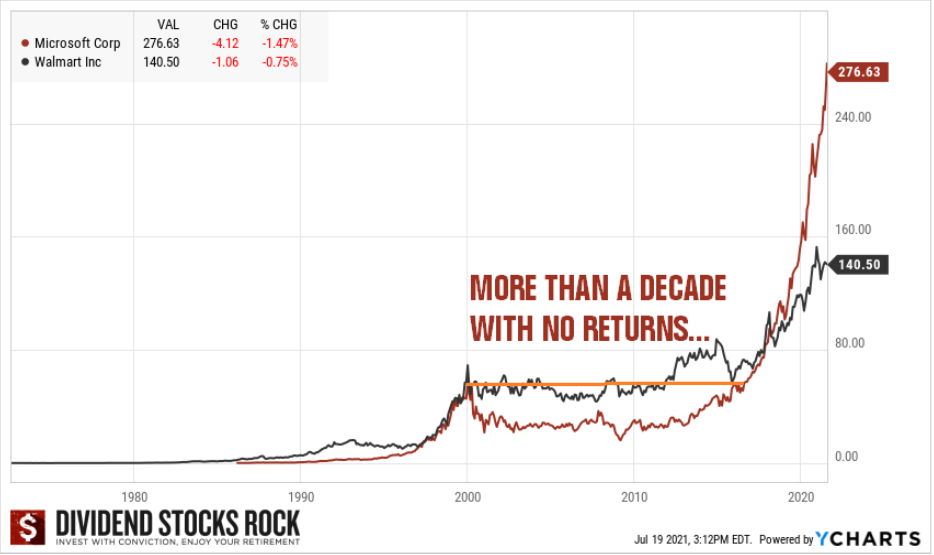

- Buy at peak value, and you could wait several years before making a penny. The examples of Microsoft (MSFT) and Walmart (WMT) are shocking.

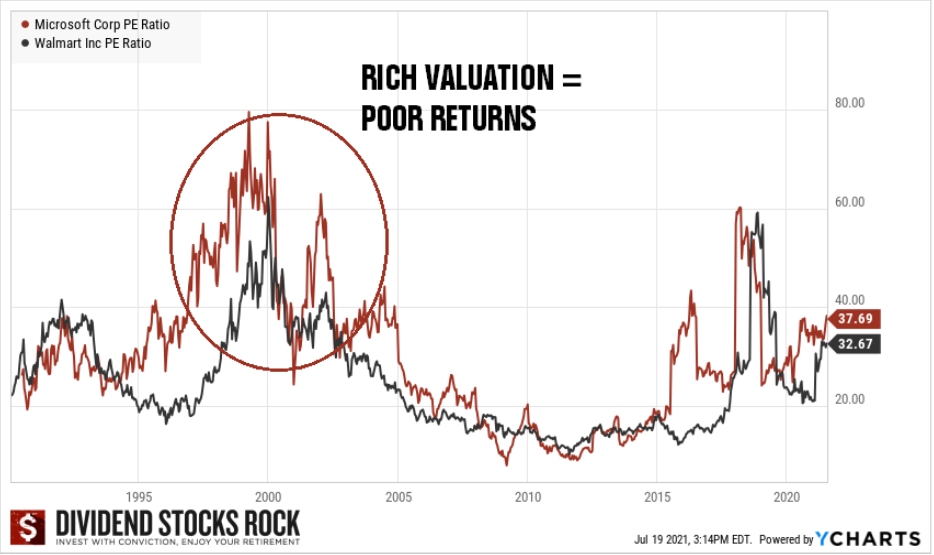

Very high P/E valuation during the tech bubble of late 90s to early 2000s

Both companies had PE ratios so high during the tech bubble that it took over a decade for investors to break even. Does it make sense to buy a well-established company at 60+ times its earnings? It never does.

How it hurts your portfolio

How is waiting for the right price a mistake? Valuation is a tricky topic explained at greater length here. In short, always waiting for the right moment to invest will make you miss several trains; you might never reach your destination.

I bought some of my top performers (triple-digit returns) at their 5-year high. I bought Lockheed Martin (LMT), Starbucks (SBUX), Microsoft (MSFT), and Visa (V) close to their so-called worst entry point. I feel blessed that I followed my investing strategy and didn’t give too much weight to valuation.

Fixing it

To focus less on valuation, add other metrics and factors in your investment process, like growth rate in revenue, EPS, and dividend over the last 5 years, etc.

Focus on the company’s growth potential; you’ll less likely wait for a perfect price that may never happen. I wish I’d bought Visa in 2009, but the second-best time to buy it was when I had money to do so in 2017.

More By This Author:

Learn To Love Company Debt

Stock Valuation: An Overview

Successful Growth by Acquisition