Artificially Intelligent

When new inventions turn into market frenzies, the contrarian part of me wants to be skeptical. But the optimistic part of me wants it to be true, especially when the idea promises to change life for the better. Reality is usually somewhere in between. And that, I suspect, is where the current artificial intelligence frenzy will go.

My observation through many cycles is that these fevers go too high, but they aren’t imaginary. The ideas are often real and so are the potential benefits; they just take longer to develop than most investors can tolerate.

AI may prove to be an exception because it is developing so fast—and is already showing tangible, cost-effective applications. This is not the 1990s pets.com sock puppet. AI systems like ChatGPT (released less than two years ago, remember) are doing things most never thought possible. Some of it is questionable quality, some may be socially undesirable or even harmful. But it’s real and improving quickly.

AI came up in many SIC sessions because it’s touching almost every corner of the market in some way. I focused on it more specifically with Joe Lonsdale and Ben Hunt. They look at it from different perspectives but had some remarkably clear thinking on this sometimes murky subject. Today I’ll share some of their wisdom with you.

But to put this in context, let’s review a piece my associate Patrick Watson recently shared with subscribers of our Over My Shoulder service, in which we send succinct summaries of interesting research. Here’s how Patrick described a pithy essay on AI by technology analyst Benedict Evans:

If you aren’t getting Over My Shoulder, you are missing out on tons of material never mentioned in my weekend letters. I highly suggest you subscribe today.

Now, to the AI conversation at the SIC, reduced to a few pages from 40+:

Statistical Engines

Joe Lonsdale has had the advantage of watching AI develop while also knowing the main players. He co-founded Palantir and now runs 8VC, a large venture capital firm with investments in AI and many related disruptive technologies. No one knows the AI big picture better than Joe. Really. As good as he does? Yes. But not many.

Joe started our SIC conversation by noting how this thing we call “AI” is really a form of statistical analysis. You may remember, way back before COVID, stories about Google’s “DeepMind” system learning to beat top humans in games like chess and Go. It did this by playing billions of games against itself, while noting what worked and what didn’t.

This wasn’t rocket science; it just required giant amounts of processing power that had never been feasible before. But something interesting happened. Here’s Joe from the SIC transcript.

“It turns out there's these simple constructs of statistical feedback where when you scale them up, it actually seems to approximate different types of intelligence really well. These are called large parameter models, or on [just] words they're called large language models, and it's basically like an engine that builds many, many abstract layers to predict the next word, the next token… So that statistical engine is the thing we talk about.

“Now most of the time we're talking about AI and it's having a huge impact on the economy, and I think it is important to think of it as a statistical thing, but in some cases it feels like it's reasoning in a lot of areas. You could train it to think in different ways to perform different tasks and we're doing a lot with it right now.”

Note those words carefully. AI “feels like it’s reasoning.” Is an AI system reasoning? Or is it just counting words in such vast numbers that it seems to be thinking? That’s not entirely clear, and on some level is an abstract philosophical question. What is “thought,” after all? We don’t have an objective definition. Though, as a human, I like to think there is a difference between a billion neurons firing and 10 billion bits on thousands of Nvidia chips firing.

In any case, Joe’s point here is critical. AI models—at least those we have now—are just statistical engines so powerful they can appear to be something else. (Ben Hunt had more to say on the dangers of that, which we’ll get to in a minute.)

AI is happening fast. I asked what this meant for jobs and the economy. Will we have time to adjust?

“You never want to say this time is different, but it's going really, really fast. And if you see adoption curves, they're happening quickly. So yeah, I think the rule holds that when you create more wealth, there's still many, many things to fix in the world, and so there's going to be many, many more and better jobs overall with where AI is right now, and it's going to create a lot more wealth, a lot higher productivity in our economies.

“Our view is you're going to actually see that show up from the productivity statistics sometime in the second half of this decade. I'm happy to be proven wrong on that, but it seems very likely from the things we're seeing.

“Is there going to be an adjustment period that's a little bit difficult because it's so fast? And there probably is, and this is a really interesting question. I happen to be in DC today as I'm talking to you, John (I think he was trying to explain AI to senators, which may be a bigger problem than creating AI), and I think one of the big things our country's facing is a rise of populism on both sides and does AI exacerbate that? It very well might at some point in the next five years.

“And that said, it could also create and should create so much wealth and it should make the living standards go up so much that hopefully the productivity thing offsets these problems, but it doesn't mean it's not going to be in for a volatile time.”

That last point struck me because the SIC also featured a panel on historical cycles which also point to a “volatile time” just ahead. Whatever disruptions AI brings will likely coincide with the Fourth Turning’s social and political events, creating whole new sets of elites, geopolitical risks, and economic disruption. I suppose AI might help us get through those times more easily. It also has the potential to go badly south.

Meanwhile, Joe thinks AI will help improve the economy by taking on some boring but necessary drudge work.

“What's the stuff that can be really improved? What's the gap in the economy? It's going after the pre-internet stuff that hasn't been upgraded, and I define that as a lot of these service parts of the economy. There is the legal part of the economy. There's a lot of financial services creating estates and trusts and whatever other work people are doing by hand.

“Healthcare billing is a huge area. We just talked about customer support earlier. Healthcare billing, John, just to give you an example. There's about a quarter trillion dollars a year, by most estimates, spent on healthcare billing in the US economy, $250+ billion. And there's people sitting in office parks and suburbs and there's millions of them and there's tens of thousands of rules per insurance company and thousands of insurance companies. It's a mess. They call it ‘revenue cycle management’ because you're cycling back and forth trying to get these things accepted. And it turns out that using AI could make the workflow… so far, we've proven it at least twice as efficient, I guess the margins are going to go up three or four times.” (It’s one of his major VC initiatives.)

Any business that can triple its profit margins by implementing AI systems is obviously going to do it as fast as possible. Joe thinks this will be widespread in the service sector, often in repetitive, labor-intensive administrative work.

This raises legitimate questions about unemployment. History shows that higher productivity creates new kinds of jobs, but the transitions can be slow and difficult. We will have to be careful on that front. However, the impact on US workers may be limited by the fact so many of those jobs have already been outsourced overseas. The impact will literally go around the globe.

In 1800, the vast majority of jobs were agriculture related. It was still very high 50‒100 years later when industrialization really began to kick in. But we had four generations to transition farm jobs to factories and other businesses. Even then it was gut-wrenching for many workers.

Now we’re going to do that in 10 years? Or less? Hmmmm…

“I Think the World Moves in S’s”

When we went to audience questions, someone asked Joe about China and AI. Is it possible Chinese engineers could challenge the current US lead? Joe doesn’t think so, but not for technological reasons.

“China, I think, is a much worse environment to operate in. A lot of our Chinese billionaire friends have disappeared, seem to have been killed. Some have fled. Xi Jinping acted very strongly against the tech class and tech leaders. [He] made it very clear to you that friends don't let friends become Chinese tech billionaires because that's a very dangerous thing to do.

“And so, what's interesting is a lot of the top entrepreneurial work, including AI in the US, is led by those of us who've already built big companies and then you can do more, and you can put lots of capital to work and you can help others and do it again. It's just a very positive feedback loop in the US because we're allowed to keep our wealth. We're allowed to speak out when we want. At least, that's the way it's been in the past.

“And so a lot of people, whether it's Elon, whether it's Sam Altman who's built other companies, whether it's Mark Zuckerberg, they're very powerful people pushing hard to build this wave here and to bring in talent and do that. So, the US has a huge advantage.

“In China, almost nobody who's successful wants to do another one because it's dangerous and it doesn't really add to your quality of life. It makes you a much bigger target. So China screwed themselves over. Europe seems to have a pretty bad regulatory environment as well. The US is also just way, way ahead and building very quickly here. So this is a hugely positive thing for the United States.”

Joe agreed China has loads of talented technologists. The skills are there. What’s missing is the entrepreneurial freedom we enjoy here in the US. In the US you can start a successful company, exit, and then use your profits to do it again. That’s difficult in China and becoming more so under Xi Jinping.

We wrapped Joe’s interview with perhaps the most important question. Will AI replace the need for humans? Are we reaching the “singularity” Ray Kurzweil talks about? Where will we be 15 or 20 years from now? Joe’s answer:

“It reminds me of the Dune science fiction as well, where they had to go on a jihad against all the thinking machines because it was too scary. They were going to break things or take over. I think it's very hard to know what's going to happen 15 or 20 or 30 years out. This is not a worry for me in the next decade. I think when it does become a worry, we're going to understand better what the danger is and how to confront it.

“It's not just about the singular human mind, it's about it being better than groups of people too and coordinating. So, when is the AI better than everyone at OpenAI itself at designing AI? That's really a singularity question, right? When is AI itself actually better at furthering its own improvement than the people and how does it accelerate? What does that look like?

“And I think a lot of people who are in the field think there's a good chance it gets there in 15 years, and it's a possibility. My bias, John, is the world doesn't go in these singularity exponentials very often. I think the world moves in S's. I think things change quickly and then they level off for quite a while, and they change quickly, and they level off for quite a while. My guess is that God didn't build quite as simple of a universe as some of these computer scientists think and that there might be multiple more S's still to go.

“So I'm not as nervous about it, but I do admit this is a real issue to think about for 20 years ahead.”

I like Joe’s description of progress as an S-curve. The sharp ascents give way to longer periods of relative stability. We’ve seen that in many different technologies and I suspect AI will be similar. We will have time to muddle through the problems.

But that doesn’t mean we won’t have problems.

The Monster with a Mask

Ben Hunt is a man of many talents. The last few years (decades?) he’s been studying “narratives,” the ways powerful people with agendas try to influence not just what we think but how we think. The latest generative AI systems are proving quite useful to the narrative-pushers.

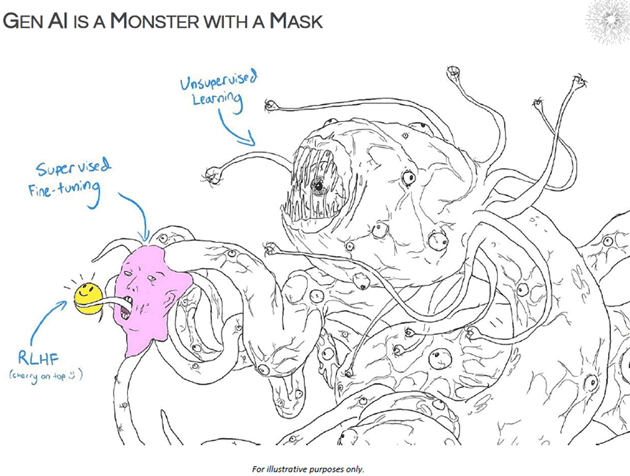

Ben says we need to recognize AI for what it is. He began by showing this cartoon.

Source: Ben Hunt

We see an ugly creature holding a masked human figure and finally a happy, smiling little face. What’s that about? Here’s Ben.

“Generative AI is an alien. It’s not kind of, sort of different. It’s an alien—my view—life form. I don’t know if anyone here remembers, David Bowie gave an interview way, way, way back in, start of the internet. And he was asked, ‘What is the internet?’ and he was like, ‘Well, it’s an alien.’ And he was totally right. And generative AI is that embodiment of the alienness.

“What I mean by being an alien and this bizarro monster that sits behind everything we interact with, with ChatGPT and the like, is that it thinks, it’s understanding information in a totally non-human way. It’s completely unrecognizable to what we think our own brains are doing. Whether that’s what our own brains are doing or not is another story. But it’s totally alien and foreign to how we think.

“The way it’s understandable to us, though, is that there’s a kind of quasi-humanish mask that’s put on top of it. That’s the fine-tuning that’s put on top of the unsupervised learning that’s all happening and is the alienness of generative AI.

“So you’ve got a humanish-looking mask held in front of this alien monster, this alien creature. And then coming out of the mouth of the fine-tuned, humanish mask is the most pleasant-sounding voice in the world. And that’s the reinforcement learning-from-human-feedback piece. That’s the piece that we’re actually interacting with. That’s the piece that’s answering our questions and doing it in the most helpful way possible.

“Because all of this, the masks that are placed onto the unsupervised-learning alien monster, the direct interaction, the voice that we are hearing, it’s designed to please us. If you get nothing else out of this presentation, get that—that generative AI is designed, with the fine-tuning and then the reinforcement from human feedback that’s put on top of it, it’s designed to please. It’s designed to make us happy. And it does.”

Remember Joe’s point about AI being a statistical engine. It learns, statistically, that giving people the answers they want usually elicits positive feedback, and so does more of it. The smiling-face AI keeps us happy with the output the ugly creature produces out of our view. Whether the output is correct is a different matter.

While perhaps useful in certain applications, this characteristic of AI can also go badly wrong. System designers and “trainers” are working on the problem. The systems have to be taught how to evaluate knowledge, knowing what to accept and what to reject. This is hard, not least because the systems train on an internet where false information abounds.

For now, the answer is patience. We all need to treat AI for what it is: a promising new technology that is currently riddled with flaws. It will improve, and far beyond what we can now grasp intellectually. But we have to look beyond the happy face and remember the AI isn’t human. It’s not a real person, no matter how chatty and amiable it seems.

We’ll need new ways to interact with these alien creatures. I am confident we can do it. But meanwhile, check everything the AI says.

Cape Town and Software Memory Lane

In nine days, I fly to Cape Town for a speech. Over 24 hours door to hotel room. The joys of travel—on Delta which will be a new international experience for me. Then not sure where till I go to BC for a salmon and halibut fishing trip with a lot of friends.

Writing this letter brought back memories of my first computers… and software. My first real productivity enhancement was WordPerfect. I think I stopped using it sometime in the 1990s when I grudgingly adopted the inferior but ubiquitous MS Word, which thankfully improved. Somewhere in a warehouse in Dallas is an old computer which, if it hasn’t melted, still likely has copies of my WordPerfect files.

So many changes over the years and the hits just keep on coming. And AI could make that seemingly rapid pace look like a proverbial turtle. In 1982 dollars, the powerful laptop I use now is under $400. And exponentially more useful and yes, powerful.

More By This Author:

An Inflation ConversationChinese Exceptionalism

Liminal Space