Inside Baseball: How We Build Portfolios

Painting is by my father, Naum Katsenelson. Prints available on Katsenelson.com

I'm about to share Part 2 of my letter, where I'll take you deep into the "inside baseball" of our investment process. Specifically, I'll discuss how we structure and determine the position size of each stock in our portfolios – something I haven't covered before (at least not in this detail) and haven't seen other investors discuss much either.

If you read my articles primarily for the stories, feel free to skip this one. But if you're a serious weekend warrior investor, don't skim – read this carefully. This portfolio construction framework is crucial, because it skews the portfolio toward higher returns per unit of risk, where risk means permanent loss of capital. While this is just one module of our investment process, it's an exceptionally important one.

Inside Baseball: How We Build Portfolios (Part 2)

An investment process is a living organism because it’s applied by living creatures. We continue to improve it and have made considerable strides over the years. The biggest leap came in 2016, caused by a very difficult and quite painful 2015 (I wrote about pain being a great instigator in the “Pain, Opera and Investing” chapter of Soul in the Game). Then in early 2019, our investment process took another significant step forward by assigning ratings to our companies across two dimensions:

- Quality: The highest quality companies were graded A, the lowest D

- Valuation: The cheapest companies were assigned a 1, the most expensive a 4

This may not look like much, but it helped us quantify our otherwise very qualitative research and substantially improve our portfolio construction.

Rather than resting on our laurels after our recent success, I wanted to capitalize on what we had learned and improve what we do. In reviewing our positions over time, I discovered a bias – I didn’t like giving C and D grades. I realized that the scars from a decade of attending school in Russia and receiving poor grades were stronger than my rational assessment of these companies (side note: I used to teach investing at the University of Denver but quit because I hated giving out bad grades).

On the one hand, this might not seem like a big deal; after all, we only wanted to own A and B companies. But the original intent of this system was to take the highest quality layer of the global stock market and segment it into four useful categories. My aversion to C and D grades flattened the nuanced qualitative understanding we had developed about these companies. We needed a new rating system that captured these distinctions.

And so we have changed our ratings to A, B, B-, and V. Here’s what those grades mean:

- A: A company with an unassailable moat, incredible management, flawless balance sheet, high return on capital, high recurrence of revenues, and a non-cyclical business.

- B: A company with many of the characteristics of an A, but which has a certain flaw. Maybe its revenue recurrence may be lower, or we don’t have enough data to fully evaluate management. To be clear, the management isn’t “bad” – if it were bad, we simply wouldn’t buy it. There is just some factor about it that makes the company lower in quality than those we give an A to.

- B-: Could be an A or B company in a cyclical, commodity business, located in a riskier country (for example somewhere in Latin America). Or could be an A or B non-cyclical company in the early phase of a turnaround. In either case, these firms face transitional “headwinds” that quality companies can work through, making it lower in quality than B companies.

- V: A, B, B- companies are solid compounders that are aimed at growing while preserving capital. But certain public companies are early in their corporate journey and offer substantial asymmetry of returns. If they succeed, they may go up as much as 5-20x, but if they fail, losses may be as high as 100% (though in the companies we’ve looked at, they seem closer to 30-50%).

These “venture” companies are disruptors, typically run by founders who have skin in the game. Most importantly, they have a long-term runway for earnings growth, with a large market and a significant chance of capturing a substantial share of it.

We’re not becoming venture capitalists and won’t have a portfolio of V's, but we’ve bought a few of these over the last few months – I’ll mention them later in the letter. This shift introduces significant asymmetry to our portfolio at the edges. The core of it will continue to be A/B/B- stocks, while V's bring extreme optionality and hopefully returns.

Currently, across all clients and all strategies, we own 33 stocks in our portfolio: 10 A’s, 12 B’s, 8 B-’s, and only 3 V’s.

As companies evolve, so do their ratings. Ideally, we want Vs to turn into As. That’s the evolution we look for – companies that mature from disruptive potential into established quality.

For example, Microsoft in the early 1980s would have been a startup, run by ambitious founders who aimed to put a personal computer on every desk and in every home. It was a bold, contrarian vision at the time, but it was also one of many young software firms chasing a rapidly evolving market.

Microsoft graduated to a V rating in the late 1980s after it won the DOS wars with IBM and secured its place as the de facto operating system provider. Arguably it became a B- a few years later: the upside remained substantial, but questions emerged around potential competition and the durability of its moat.

By the mid-to-late 1990s, Microsoft had clearly become B and then an A – it had established an unassailable moat in operating systems and productivity software, generated enormous recurring revenue, and built one of the strongest balance sheets in the market.

Our rating system is a continuum that captures companies across their entire lifecycle as they move up the quality spectrum and even down (this happened to one of our companies in 2025). As they move up, so does our tolerance for increasing their position size in our portfolio (which I discuss next).

To be clear, C and D companies haven’t completely disappeared from our process; we encounter them frequently during research, but we just are not interested in them.

What constitutes C or D companies? Simple: they are not quality. I like Warren Buffett’s definition of quality: if the stock market were closed for ten years, would I be comfortable holding this stock?

Stock market liquidity – the ability to buy and sell at any time – often turns investors into traders. Buffett’s quality framework, however, puts us firmly in the seat of an investor. C and D companies are those that fall into the “not comfortable” bucket.

The beauty of our approach is that with 10,000 publicly traded companies globally and perhaps only a thousand or two meeting our quality criteria, we can afford to be extremely selective. We don’t need to compromise on quality when there’s such an abundance of opportunities to choose from – we only need to find 25 stocks.

The Power of Combining Quality with Valuation

Up to this point we’ve discussed company quality and ignored valuation – what the business is worth and how much we should pay for it.

Our valuation analysis involves two extremes: smothering the business in our models with a pillow (stress testing for when “life happens” – i.e., declining margins, slowing revenue growth, worsening unit economics) and, just as importantly, envisioning its full potential. Through this exercise, we arrive at a range of values.

The worst-case scenario sets our floor. If we think the company is worth $50 in a disaster and $100 in the most probable scenario, we don’t want to pay much more than $50. This is our margin of safety.

Our quality rating system becomes incredibly powerful once it’s married with valuation analysis. We spend hundreds of hours researching stocks to arrive at these two inputs (quality and fair value). Here’s how combining these ratings works in practice using a grossly simplified example (I use significantly oversimplified numbers here, but they are directionally similar to what we do in your portfolios).

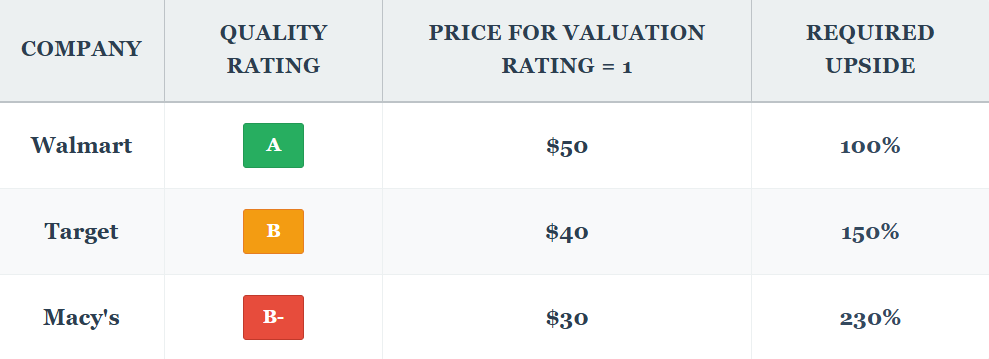

Let’s say we have three companies, all worth $100 in five years:

(Click on image to enlarge)

Between you and me, I’m not sure if Macy’s even deserves a B-, but let’s use it for illustrative purposes. The pattern is clear: the lower the quality, the bigger the discount we demand. If all three stocks traded at $50 today:

(Click on image to enlarge)

Now, V-rated companies are a different animal entirely. These are our venture-like investments, and we’re betting on explosive return potential. For these, we size positions small (1-3%) and look for multiples of return while accepting higher risk of loss.

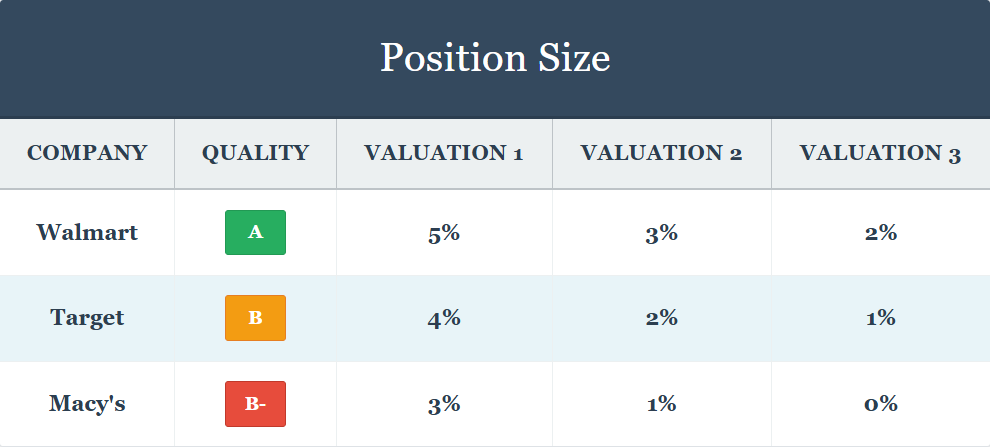

Position Sizing

The quality rating and valuation system is a cornerstone of our portfolio construction. The higher the quality of the company and the more undervalued it is, the larger its position is going to be. This makes perfect sense since higher quality reduces risk and significant undervaluation leads to higher returns.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Why is this important? This system forces high-quality companies that are significantly undervalued to rise to the top while limiting our exposure to relatively low-quality companies. If “life happens” to a lower-quality company, the impact on the portfolio is lower; however, if things work out, we’ll get compensated for taking a higher risk.

Equality of outcomes was never my thing. I love meritocracy, and our portfolio is built on merit.

Sometimes clients ask why we bother with small position sizes. There are various scenarios where this makes sense. For example, we may have started buying a B quality company when it had a valuation of 1, then the stock price went up and it became A3. We may still buy 1% for new clients.

Additionally, we may have conducted research on the company and at present believe it deserves a 1% position, but the price may decline or quality may improve – in both cases meriting a larger position size. Buying even a small position ensures we stay on top of the name.

Let me end this first part of the letter by sharing three final thoughts about our valuation process and position sizing.

First, there’s value in the process itself – deciding company quality creates creative friction as we debate whether a company is A or B and challenge valuation assumptions. Just doing this makes us better investors and enriches our understanding of what we own.

Second, quantifying position sizing removes emotions. It’s done almost automatically and calculated daily by our systems – the variable that changes most is not quality or fair value but market price.

Finally, as I was writing this, I noticed a few areas where we can already improve – and this is our goal: not to stand still, but to continually evolve.

I hope this explains portfolio construction, especially for new clients.

And One More Thing – Options

In accounts with sufficient cash and options trading permissions, we established several small options positions as hedges.

We purchased calls on gold (GLD), making a modest bet that gold prices will rise as currency debasement continues. We also bought puts on 20-year treasuries (TLT) to hedge against potential spikes in long-term interest rates resulting from increased money supply. Additionally, we acquired puts on the S&P 500 to partially hedge our portfolio against a broader market decline.

None of these investments serve as a panacea for current global economic conditions. The core of our returns and our ultimate success or failure will continue to depend on thoughtful stock selection.

I'd love to hear your thoughts, so please leave your comment and feedback here. Also, if you missed my previous article "Skating on Thin Ice: Discipline, Doubt, and the Long Game (Part 1)", you can view it and leave a comment here.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Drawing is by my brother, Alex Katsenelson. Prints available on ArtistUSA.com

More By This Author:

Skating On Thin Ice: Discipline, Doubt, And The Long Game

Buffett And The Berkshire Paradox

Redefine “Value” In This Era Of The U.S. Stock Market

Today, I want to share with you a special performance of the aria “Song to the ...

more