BofA: "It Is Unrealistic To Have Widespread Vaccine Availability In Q1 2021"

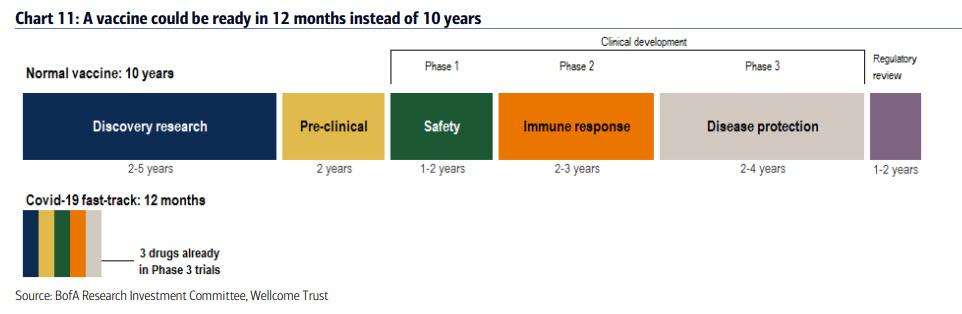

As Deutsche Bank wrote at the start of August, although vaccines normally require years of testing and additional time to produce at scale, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic scientists are hoping to develop a coronavirus vaccine within an extremely truncated timeframe of only 12 to 18 months. While a vaccine typically takes years to develop using a traditional process, with COVID-19, things are far more accelerated.

Especially with BofA showing how what is typically a ten year process could - in theory - be compressed to just 12 months:

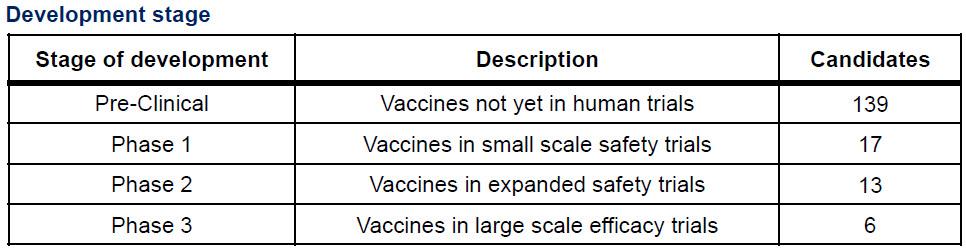

Furthermore, there are already no less than 160 coronavirus vaccine candidates currently in process, as the following table shows:

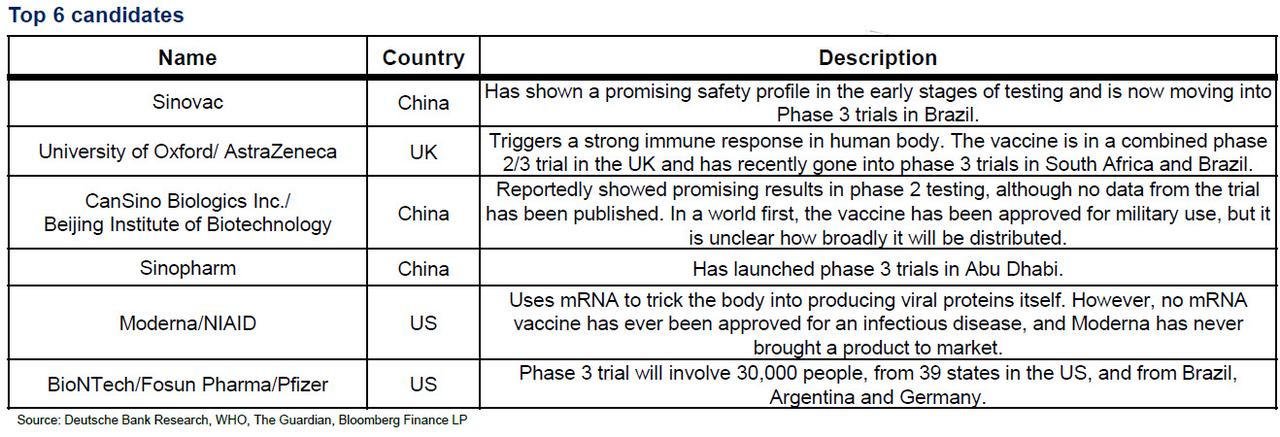

As well, here are the top 6 listed below.

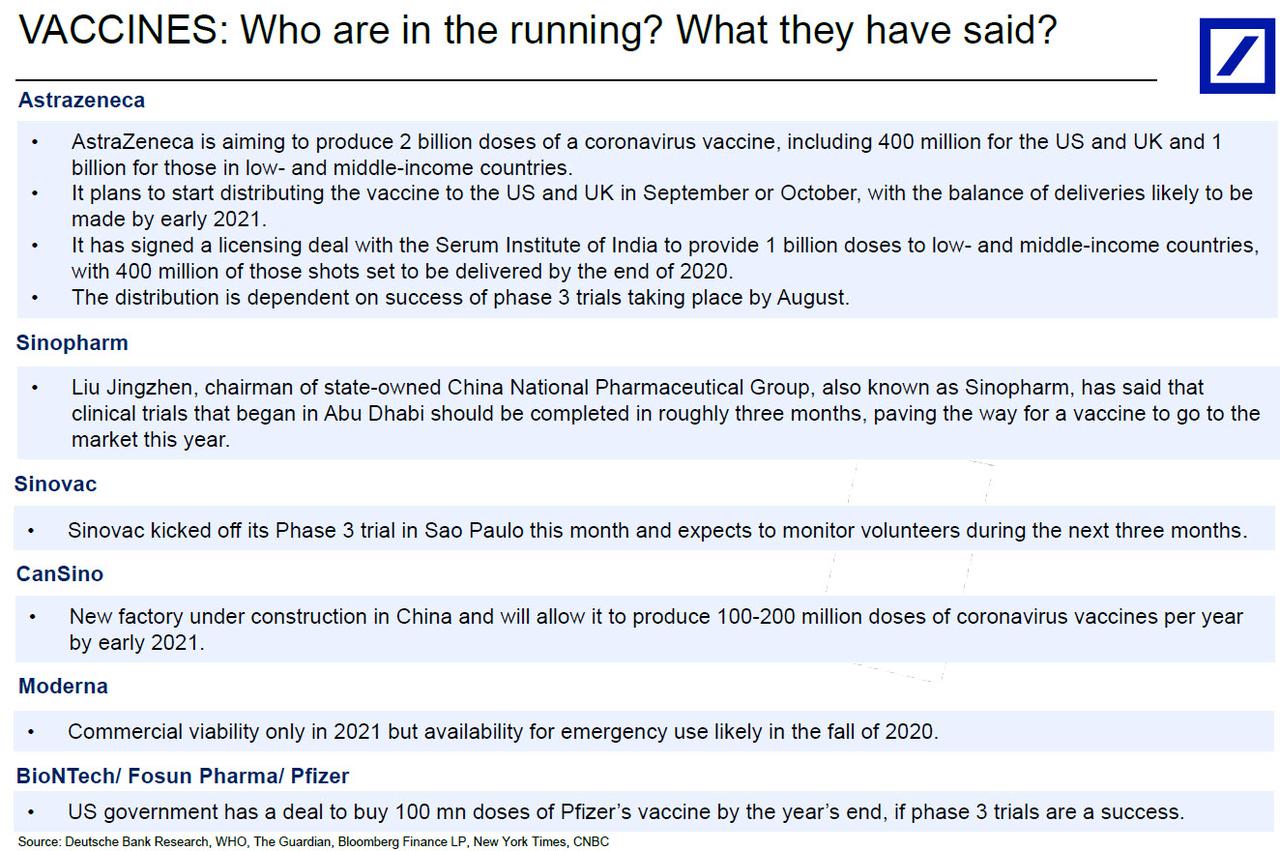

Here is what the top vaccine makers have said publicly about the state of affairs courtesy of Deutsche Bank.

Still, there are caveats and there is a distinct possibility a vaccine - which many sellside analysts view as a "magic bullet" to rebooting the economy and re-normalizing pre-coronavirus growth rates - may not emerge any time soon as various roadblocks remain.

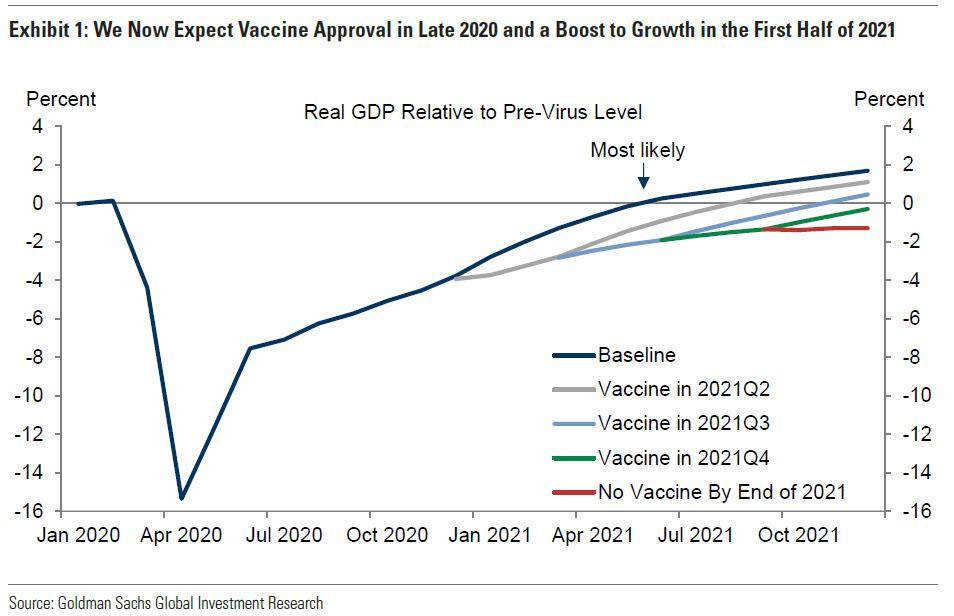

That, however, did not stop Goldman Sachs (GS) from boosting its economic outlook and raising its GDP forecast for 2021 for one simple reason: as we reported two weeks ago, the bank now believes that "at least one vaccine will be approved this fall with widespread distribution and positive growth effects felt in the first half of 2021."

As a result, Goldman now expects GDP growth of +10% in Q1 2021, +8% in Q2 2021, +4% in Q3 2021, and +3% in Q4 2021 (an upgrade vs. +8%, +6.5%, +5%, and +4% previously). This raises 2021 growth to +6.2% on an annual average basis (vs. +5.6% previously) and +6.2% on a Q4/Q4 basis (vs. +5.9%).

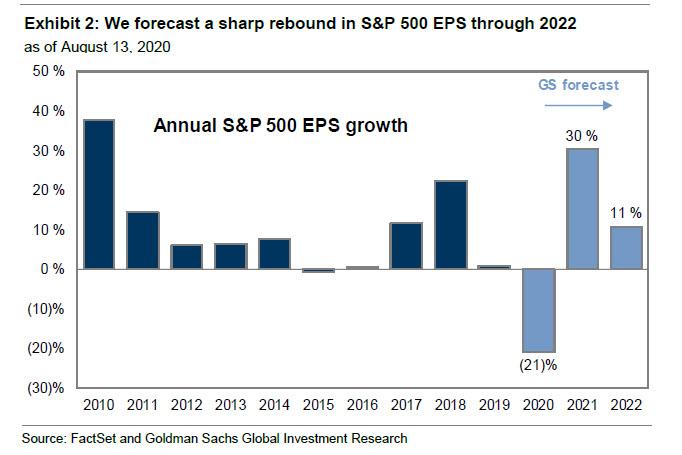

This renewed economic optimism also prompted the bank's chief equity strategist David Kostin to raise both his EPS forceast and his S&P price target to 3,600 last weekend (the real reason is that the S&P had run far away from Goldman's prior S&P price target of only 3,000, and the bank had to find a new reason to become more optimistic).

Not everyone is that optimistic, however.

Countering Goldman's cheerful outlook, Bank of America (BAC) last week wrote that it does:

"...not think that it will be realistic to have widespread vaccine availability (hundreds of millions of doses) in the US and Europe sometime in 1Q21. We think that there are considerable vaccine process development and manufacturing risks, which could compromise sufficient and timely vaccine supply, including potential setbacks in process validation, scale up, technology transfer, raw material shortages (e.g., glass vials), etc. Outside of the US and the main countries in Europe, COVID-19 vaccine supply could also be compromised by 'vaccine nationalism' (that is, the rich countries of the world prioritizing and hoarding vaccine supply domestically before making vaccine(s) available elsewhere)."

Elaborating on this skeptical timeline view, in a note from Bank of America last week titled "The economics of a vaccine," the bank's chief global economist Ethan Harris wrote that it will take a significant amount of time from proving a vaccine is effective to distributing it broadly to the population. The lags include:

- Production time (unless it is one of the candidates doing production in advance),

- Distribution (requires setting up drive-throughs and other broad distribution systems),

- Second shot (a few weeks after the first),

- Time to determine efficacy (roughly a month), and

- Time to uncover longer-term side effects and durability (a year, perhaps).

Harris then writes that in listening to the experts, including our healthcare analysts, there are a number of potential pitfalls in developing, producing, and distributing a vaccine. Three stand out to Bank of America:

1. Partial success. Talking to healthcare analysts, success in finding a vaccine is not a binary outcome. Vaccines can be approved even if they only provide protection for half of the people taking them, may prevent serious illness rather than prevent infection altogether, immunity may not last long, particularly if the virus mutates frequently, and side effects may be prohibitive for some vulnerable groups.

Distributing a vaccine that either doesn’t work or ends up with serious side effects could damage the economy more than having a long delay in finding a vaccine.

2. Vaccine nationalism. There is already a scramble to be first in line for the vaccine, with a number of countries lining up supplies for one or several of the candidate vaccines. Here, BofA worries about history repeating itself. Early in the crisis, there was a similar scramble for masks and other supplies, with a variety of efforts to hoard supplies. Will this compromise the efficiency of production and distribution across global supply chains?

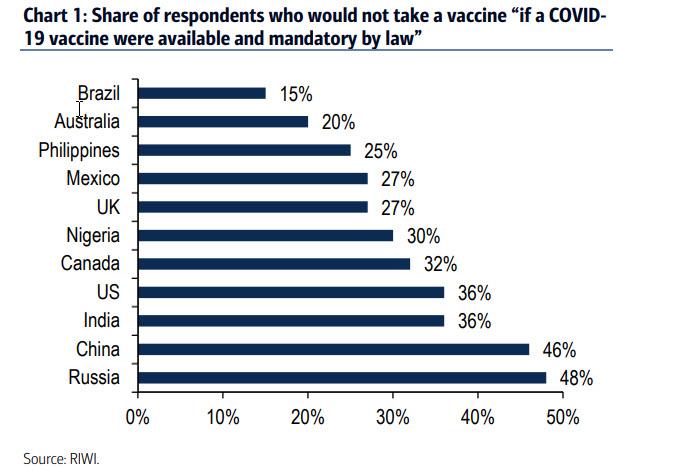

3. Vaccine phobia. Even in the best of times, many people refuse to get a flu shot. Americans seem particularly skeptical about public health policy. If masks are unacceptable, what about shots of a brand new drug? A RIWI survey in June and July found big differences across countries (Chart 1). This would suggest that if anything, the initial take-will be very slow.

After all, there have been a lot of confusing public health messages, particularly in the US. Yet even BofA admits that "such caution is to some degree warranted, with the vaccines being rushed to market without knowledge of the long-term side effects."

Why all the focus on vaccine timing? As Harris continues, reading the commentary in the press, he gets the sense that many investors see a vaccine breakthrough as a game changer, quickly pushing the global economy back to full employment.

In Harris' view, while that may have been the case had there been a miracle cure or vaccine in the Spring as it would have shortened the shutdown and avoided deep damage to the economy, however, over time the story has shifted and is continuing to shift. Economies have all reopened to some degree. People have learned to function with the virus and have restructured activities accordingly.

We can see this in the way countries that have not contained the virus—like the US—can “bend the case curve” with relatively modest changes in behavior. Still, we must also contend with headwinds to growth from second-round effects: the damage to confidence and balance sheets, businesses slowly (and not so slowly) going under, and investment plans being canceled.

"It is worth hammering home this point. Every recession starts with one or several shocks and yet continues even when the shock abates. Consider two factors that are important in many recessions: central bank tightening to fight inflation and surges in oil prices. Both generally reverse over the course of the recession and yet the downturn continues. A classic example is the recession of 1982."

It is also important to note that rolling out a vaccine will not immediately end all social distancing behavior. Some people will respond quickly as pent-up demand is released, taking that long-delayed vacation, for example. However, the majority of people will re-engage slowly as they become more comfortable that the health risk is indeed gone.

Some activities could take very long to fully recover. One final headwind: after pouring stimulus into the economy, developed-market monetary authorities are almost out of ammunition and fiscal authorities will likely pull back a bit, letting the economy wobble along on its own.

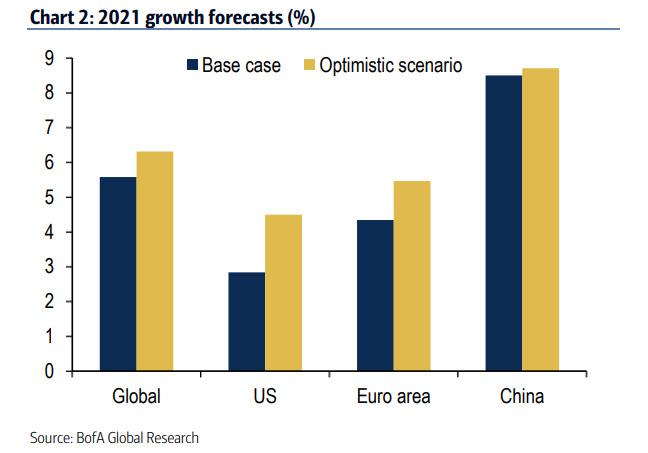

So putting it all together, BofA's baseline remains unchanged (and not in pursuit of goal-seeking a narrative driven by the S&P 500's relentless ascent), namely that a vaccine is widely disseminated in the developed world in 3Q 2021, but rolls out much more slowly in parts of the developing world. Under a "realistically optimistic scenario," BofA simply assumes the process is accelerated by two quarters so that the roll-out is in 1Q rather than 3Q.

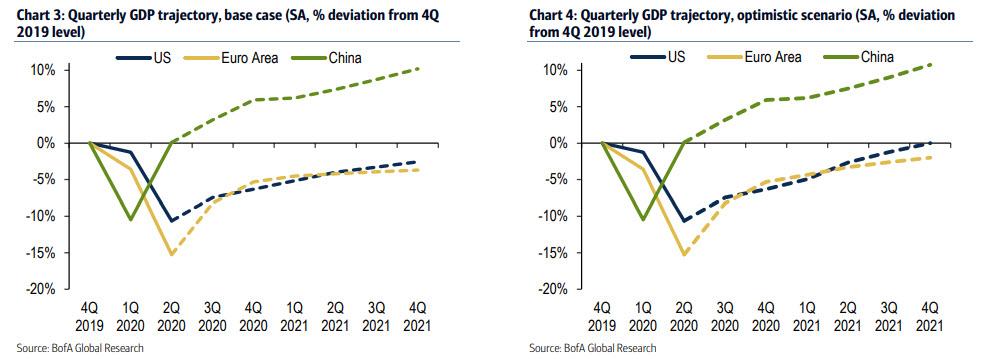

BofA's "realistically optimistic scenario" for growth,which incidentally coincides with Goldman's new baseline, is shown below.

Globally, in the event of a vaccine, BofA expects the addition of 70 bp to growth in 2021. The stimulus varies across countries. In general, countries that have had the most trouble containing the virus will tend to respond more to a vaccine — hence, the US benefits more than Europe, which in turn benefits more than China.

As Chart 3 and Chart 4 show, an early vaccine would allow US GDP to return to 4Q 2019 levels by 4Q 2021, although the output gap remains as growth lags potential; Euro area GDP would not quite return to 4Q 2019 levels even with an early vaccine, largely because fiscal stimulus has been too small and too delayed.

China is expected to surge even in the base case, as the virus is already largely under control. But, GDP should still remain below potential through the end of next year in both scenarios.

Similarly, there is limited upside from an early vaccine in most of emerging Asia because so much progress has already been made in staving off the virus. Other emerging markets should benefit more than EM Asia, but less than DM, because broad inoculation will probably happen a little later.

Disclaimer: Copyright ©2009-2020 ZeroHedge.com/ABC Media, LTD; All Rights Reserved. Zero Hedge is intended for Mature Audiences. Familiarize yourself with our legal and use policies every ...

more