Inflation And The Intergenerational Housing Rivalry

Image Source: Unsplash

Housing is not special. That is, real estate and houses are not outside the laws of economics (i.e., scarcity, etc.). That said, each economic good necessarily offers something unique (otherwise it would be indistinguishable from other goods) and therefore comes with its own benefits and challenges. For example, the laws of economics apply to land and bananas, however, while land and bananas may both be valued in the estimation of human actors, they not only offer different utilities, there are differences in the markets for land and bananas because of the nature of the goods. Put another way, banana markets have to concern themselves with perishability when considering bringing bananas to consumers while sellers of real estate have different concerns. Land is an originary factor of production and real estate and housing are usually durable consumer goods.

In a previous article, I examined how interventions and inflation—by creating imposed inequality and caste conflict where some benefit at the expense of others—contribute to intergenerational resentment, especially between older generations and younger generations. This is evident in the cross-purposes and rivalry an inflationary economy creates between the old and young when it comes to real estate and housing. Under a free market and sound money economy, real estate and housing would not likely be an ideal investment good, however, under an inflationary economy, the constant devaluation of the currency encourages the exchange of currency units for durable goods (like real estate), which tend to appreciate as assets in an inflationary environment. This tends to benefit the older and wealthier—who generally are more likely to already hold more real estate and financial titles—at the expense of the younger and poorer, who exchange their labor for depreciating currency and who thus must work and save much more to acquire real estate.

An Inflationary Environment and Real Estate as an Investment

This argument, although stated by others, was recently presented by Saifedean Ammous on an episode of the Tom Woods Show, in which he discussed his new book: The Gold Standard: An Alternative History of the Twentieth Century.

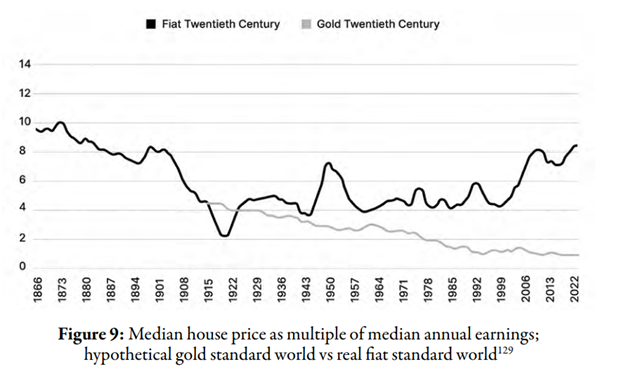

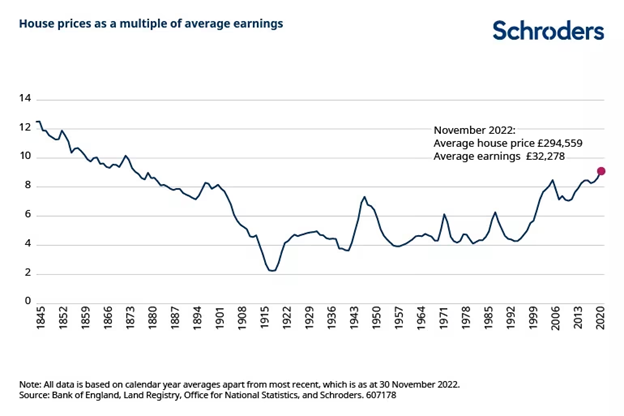

Under a free market, including sound money, the prices of real estate and housing would be determined by supply and demand. With increased production and better technology and moderate deflation that gradually increased money’s purchasing power, we would expect housing to gradually become more plentiful and to thereby become cheaper over time. Empirically, this was historically the case under freer markets and sounder money. Ammous presents (p. 352) an adapted version of a chart that demonstrated a history of falling housing prices:

Note that both charts trace housing prices as they decreased until around 1915, but then this trend reversed and housing prices increased as sound money was eroded in the twentieth century. Ammous explains,

For centuries, humans have increased our productivity and made the production of houses less costly in terms of our time. For centuries and millennia, houses have become more affordable, but this trend reversed with the plague of fiat money befalling humanity in the twentieth century. As people began using their homes as savings accounts, much of the monetary demand that would have otherwise gone into hard money investments shifted to housing. Consequently, housing prices outpaced the rise in income. Going off the gold standard in 1914 stopped a centuries-long increase in the affordability of homes by degrading the value of money,... (pp. 353-354)

In other words, due to an increasingly inflationary environment, there is an incentive to treat real estate and housing as investment goods rather than durable consumer goods. When supply restrictions are added (e.g., regulations, zoning laws, etc.), combined with increased demand for housing, real estate not only tends to hold value but to appreciate. People who are able to do so understandably trade in their depreciating dollars for real estate assets. Similarly, those who purchased real estate earlier (now older) realized a gain because of price appreciation in their houses. And, as with any investment, people in these circumstances want their investment in real estate to appreciate, not depreciate. In a recent podcast interview, Karl-Friedrich Israel similarly stated,

Even if everything works out as intended [by the central bank aiming at two percent inflation], we are very likely to have overproportionate asset price inflation for very simple reasons. If you create such an inflationary environment, it changes how people behave. So there is, first of all, a shift in saving behavior, right? You have two percent inflation, on average, over time, you try to protect your savings in some way, so you have an incentive to redirect your savings asset categories that protect you from inflation. So, for example, you buy real estate, you buy stocks, you buy Bitcoin, you buy precious metals, etc. Anything that can protect your savings from inflation. And so there is this shift in the demand for certain assets and this creates an overproportionate price inflation for those assets…. So now the problem is, overproportionate asset price inflation is good for all the people who already own assets, but it’s very bad for those who don’t. So the difference—the gulf—between the “haves” and the “have nots” increases because of asset price inflation.

Under extreme circumstances, such as hyperinflation, in which a system has inflated so much that the money will shortly be abandoned, prices are skyrocketing, and the purchasing power of money evaporates, there can be what Mises called a “flight into real values” instead of money. Under less extreme circumstances, it can be argued that there is a slower and partial “flight” or shift into “real values,” like real estate, away from depreciating money.

With sound money, it is unlikely real estate would be viewed as a key investment good, at least to the extent that it is. Sound money would mean that money would maintain its purchasing power over time and—with increased production and efficiency—goods would get cheaper and the same monetary units would purchase more. This moderate deflation would mean that real wealth and income would increase over time. In other words, people could realize an appreciation in the value of their money just by saving (though other investments would exist as well). But, under unsound money and in an inflationary economy, money does not hold its value, which causes people to seek appreciating investments elsewhere. Ammous argues,

The reason houses continue to become more expensive in our world is that they serve as a store of value, given the inability of money to fulfill that role. In fiat world, buying real estate is one of the most reliable ways of saving for the future. (p. 352)

While this behavior is understandable, it is a result of an inflationary environment and intensifies intergenerational resentment and rivalry.

Inflation, Housing, and the Young

As younger generations—who do not typically hold real estate or financial titles—grow up in an environment of depreciating purchasing power and increasing housing prices, their demand for real estate not only competes against other younger people who seek real estate to live in, but also against older, wealthier generations who already hold real estate and financial titles and seek to purchase more as an investment. This increased demand and restricted supply further increases housing prices. Younger people may be outcompeted and priced out of the market by older generations when it comes to purchasing real estate. The price appreciation of real estate benefits those who already own it and harms those who do not. This also means that those who own real estate and see it as an investment will be tempted to support political schemes to maintain or increase housing prices via inflationary policies. (Keep in mind 2008 where part of the panic concerned falling housing prices). This, in part, also explains why real estate and housing prices increase, even as production costs decrease,

This means that people purchase [homes] to save for the future, which amplifies demand for them beyond the demand for housing. Houses today serve as savings accounts for fiat users who lack better options. This likely causes the price of houses to continue appreciating even as they become cheaper to produce. (p. 352)

Ammous describes how this particularly affects young people,

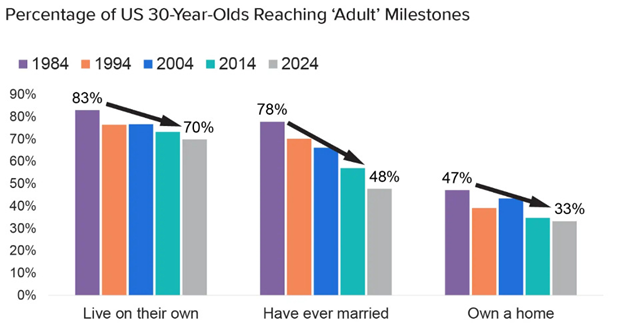

When young couples are looking to start a family, they are not bidding for a house to live in only; they are also bidding for a savings account, and will likely be outbid by older people who have significant savings or by large corporations that need to hold hard assets to avoid holding depreciating money. The result is a growing percentage of people being forced to rent for the long term. This is the root of the housing affordability crisis, a hallmark of the past few decades in many parts of the world. (p. 354)

Practically, this means that several so-called “normal” adult milestones—living independently, marriage, home ownership—are delayed (see below). Add to this economic illiteracy, especially regarding the nature and effects of inflation, the high time preference habits and institutions of an inflation culture (especially among the young), and a few moral lectures from the older generations who likely have unknowingly benefitted from inflation, and you have a recipe for intergenerational contempt.

Guido Hülsmann—in discussing the cultural impacts of inflation—discusses how inflation has different impacts on different generations and also hints at the disparity in housing,

Now permanent price inflation comes with a heavy cost—heavy social cost—most notably in the form of the redistribution of wealth in favor of the “haves” and to the detriment of the “have nots.” In an environment of permanent price inflation, perishable goods are traded at a discount and durable goods—which help us to protect our wealth against the loss of purchasing power of the money units—trade at a premium. Now what are the most durable goods? Real estate and financial titles. What are the most perishable goods? What’s the most perishable good? Human labor. Human labor cannot be stored any second…. So as a consequence then, labor trades—in an inflationary environment—at a discount, as compared to durable goods, such as real estate and financial titles. And this manifests itself in the increasing difficulties of the rising generation to accumulate wealth. It just takes many more years of work and increasing saving rates to catch up with the level of wealth that has been accumulated by previous generations, in a shorter time and with lower savings rates. Now the data are very clear in that respect…. It is harder for younger people, harder for younger families just to catch up.

Likewise, in a lecture at the Mises Institute titled “Economic and Social Consequences of Inflation,” Karl-Friedrich Israel described both the relative effects of inflation on housing prices, which increase massively relative to consumer prices, and how inflation increases inequality and hampers social mobility. He cogently identified channels of redistribution of wealth due to inflation, that is, from whom the wealth is transferred and to whom it is transferred—from private to public, from relatively poor to relatively wealthy, from labor income to capital income, and from younger generations to older generations. Thus, younger generations—typically more dependent on labor income and having not accumulated capital (like real estate) yet—suffer disproportionately from inflation. Instead of market competition, inflation forces young and old into rivalrous competition for housing.

Conclusion

The best solution to this—for old and young—is sound money. The best policy solution would be separation of money and state, however, the situation could also be ameliorated considerably by repealing legal tender laws and allowing currency competition. In a recent podcast appearance, Karl-Friedrich Israel compared stopping inflation to “taxing the rich,” arguing, in essence, that ending inflation would restore a more economically sound and just system that does not artificially redistribute wealth through the hidden tax of inflation.

More By This Author:

The Next Economic Downturn Will Be Here Soon EnoughMoney Remains A Medium Of Exchange And Is Not A Series Of Data Points

The Government Is Lying About Inflation

Mises Institute is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Contributions are tax-deductible to the full extent the law allows. Tax ID# 52-1263436.

Note: The views expressed on Mises.org ...

more