The Placebo Effect

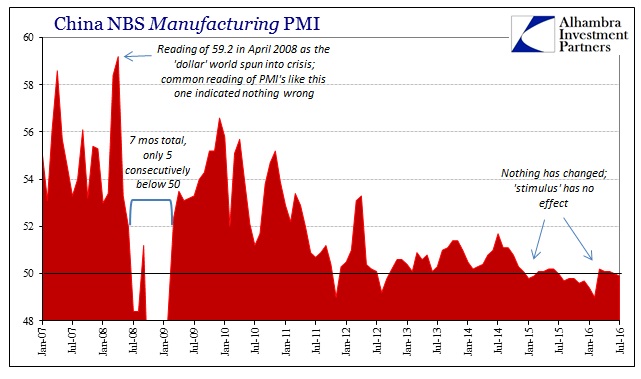

On April 1, China’s National Bureau of Statistics reported that its official PMI for the manufacturing sector had burst back above 50 for the first time since July 2015 before all the “global turmoil.” The NBS didn’t actually use the word “burst”, of course, as they simply reported the figure and economists and the media did the rest. It seemed at least possible that the difference from March 2016’s 50.2 compared to the multi-year low of 49.0 in February was significant.

It didn’t matter that these kinds of rebounds had occurred fairly regularly all throughout the past four and five years of continual baseline slowing. The winter was so very dark that anything indicating a possible change was heralded under varying degrees of unnecessary hyperbole. In this article published by Yahoo!Finance, for example, under the appropriately sensational headline Forget the jobs report: There’s a more important economic story unfolding today, the pre-determined narrative had been set only awaiting “confirmation.”

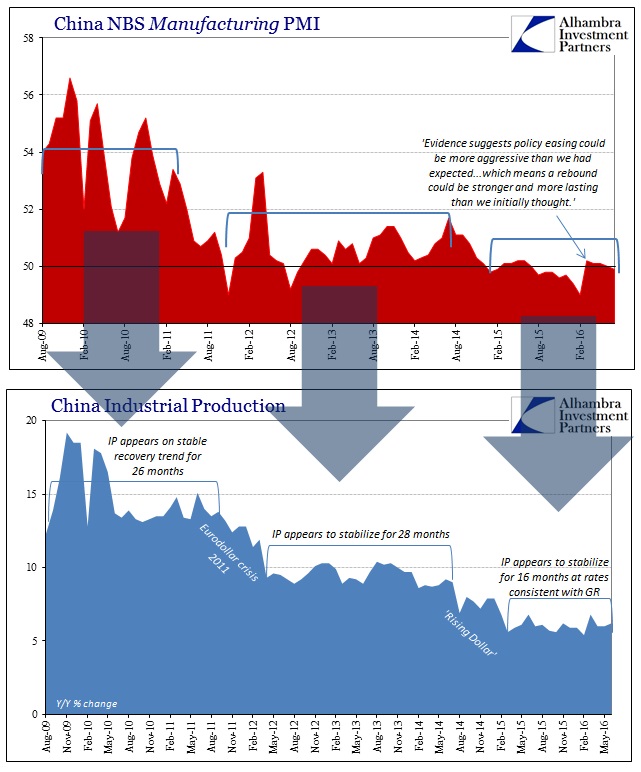

This surprisingly strong official PMI release points to stronger growth momentum in March and was largely supported by domestic demand, especially property and infrastructure investment as a result of policy easing. Evidence suggests policy easing could be more aggressive than we had expected, fiscal and quasi-fiscal policy easing in particular , which means a rebound could be stronger and more lasting than we initially thought.

That comment from Nomura’s Chief China Economist Yang Zhao reflected the intended emphasis particularly from economists who are always sure “stimulus” works. The article called the 50.2 estimate for the official manufacturing PMI “the biggest story of the day”, overshadowing everything else including the +215k rather tame US jobs report. But 50.2 is as high as the PMI would get over the intervening months. It fell back to 50.1 for both April and May, then 50.0 in June and now 49.9 in July, just under the supposed expansion/contraction dividing line.

Economists are left once more confused, including Yang Zhao quoted in a Reuters article appearing today that was sure to include the word “unexpected” both in the title and right from the outset in the text:

Activity in China’s manufacturing sector eased unexpectedly in July as orders cooled and flooding disrupted business, an official survey showed, adding to fears the economy will slow in coming months unless the government steps up a huge spending spree.

While the July reading showed only a slight loss of momentum, Nomura’s chief China economist Yang Zhao said it may be a sign that the impact of stimulus measures earlier this year may already be wearing off…

“The government has realized the downward pressure is great but they’ve also realized that stimulus to stimulate the economy continuously is not a good idea and they want to continue to focus on reform and deleveraging,” Zhao said.

“Stimulus” is apparently so powerful that it both works and doesn’t work whenever the government so chooses. In reality, China is stuck in lower growth that behaves quite erratically. However, this unevenness is nothing new as it is exhibited all across economic data and not just in China. Just last year, the PMI started off 2015 under 50 at a 49.8 and 49.9 in January and February 2015, respectively. From there it rebounded to 50.2 in both May and June before “unexpectedly” slumping back slightly in July.

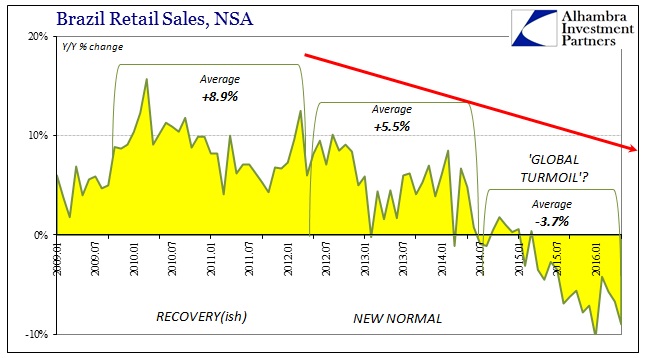

It is not these minor variations that are significant; if anything they are misleading and at times highly so (especially for economists). Instead, the PMI in China, again as economic data elsewhere around the world, shows three distinct “phases” or settings. There was more conforming growth indicated earlier in the “recovery” that while somewhat short of symmetry compared to the size of the hole of the Great Recession made a full recovery seem at least plausible. After the events of 2011, really starting in 2012, growth dramatically downshifted but then appeared to stabilize for several years. That process repeated starting in the summer of 2014 concurrent with the “rising dollar.”

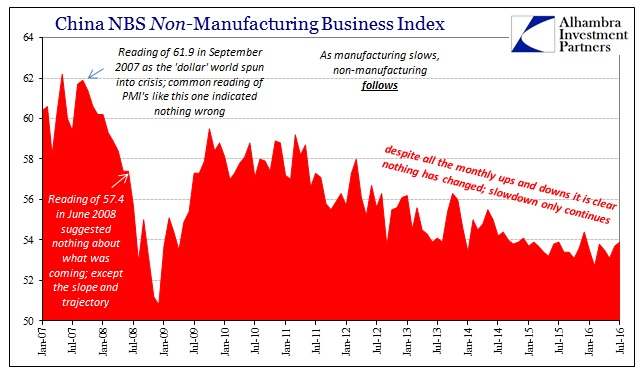

The same interpretation applies only more indirectly to the non-manufacturing PMI, which actually “improved” in July to 53.9, the highest since December 2015 (which tells you a lot about how little these PMI’s offer in the way of predictive capacity). The manufacturing PMI for China lines up quite easily with Industrial Production, not in monthly changes or even these multi-month mini-trends, but in those three “phases” of the global recovery falling further and further away from it.

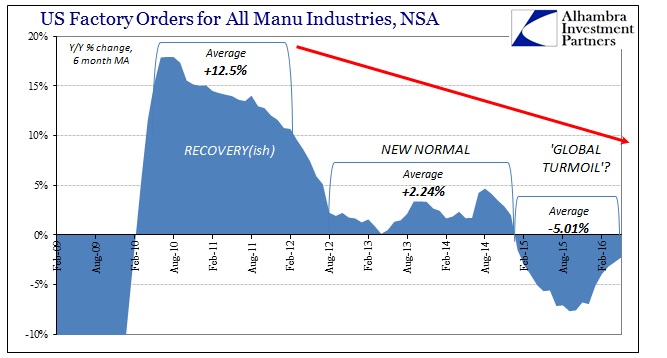

It isn’t recession but it is far, far bigger, and because of that it is well beyond the grasp of orthodox models of how any economy “should” operate. It would be alarming if it were limited to just Chinese economic misfortune, but this pattern is endemic all over the globe including and especially here in the US (which isn’t actually surprising once you normalize rhetoric about US consumers to an appropriate standard of comparison).

Continuing to analyze economic conditions under the linear, binary model of recession/not recession will only lead to this kind of confusion. While this staggered increase in monetary pressure and strangulation is more than a half decade old, that is actually the primary problem of mainstream interpretation with its intentionally short attention span of almost all economic commentary. Everything is compared to last month (especially anything with seasonally-adjusted month-over-month figures) and so if there is an improvement from last month it is incorporated as if it must be an actual improvement in a meaningful sense.

Stepping outside recession/not recession, it is absolutely clear what “stimulus” is and what it is not. It is not, obviously, stimulus in that years upon years of it all over the world have had no positive economic effect. In that way, monetary and fiscal policies have only left the real economy dealing with something like the “placebo effect”, though in reality it is worse than that. In medical terms, the placebo effect can actually bring about positive outcomes even though patients are essentially fooling themselves by believing in it. Here, across the entire global economy, the placebo of “stimulus” has had only the negative effect of allowing economists to attribute a recovery that increasingly did not and does not exist, yet so many, especially in the media, still believe it and set expectations in that manner.

The true harm, however, is that by doing so actual healing has been actively prevented and stymied. The global economy was prescribed the placebo of primarily monetary policy in lieu of actual medicine (reforming the global money system of the eurodollar), leaving it to only get sicker and sicker while central bankers instead declared it healthier and healthier. The error, like the placebo, was exposed in widespread fashion last year.

Disclosure: None.

Placebo Effect is great wording for this. Could this effect extend to anything else, however?