Negative Interest Rates

For an economy with underutilized resources or too low a rate of inflation the traditional prescription for monetary policy is to lower the interest rate. Central banks around the world tried to do that in response to stubbornly weak economies, bringing the overnight interest rate in many countries all the way to zero. But when that didn’t seem to be getting the job done, the Bank of Japan last week decided to go negative, charging banks 0.1% interest for excess reserves. With this step Japan now joins the Euro system, Switzerland, Denmark, and Sweden, all of whom have had negative interest rate policies in place for over a year. Here I describe how negative interest rates work, what they are intended to accomplish, and some of the limitations of using this policy to try to stimulate the economy.

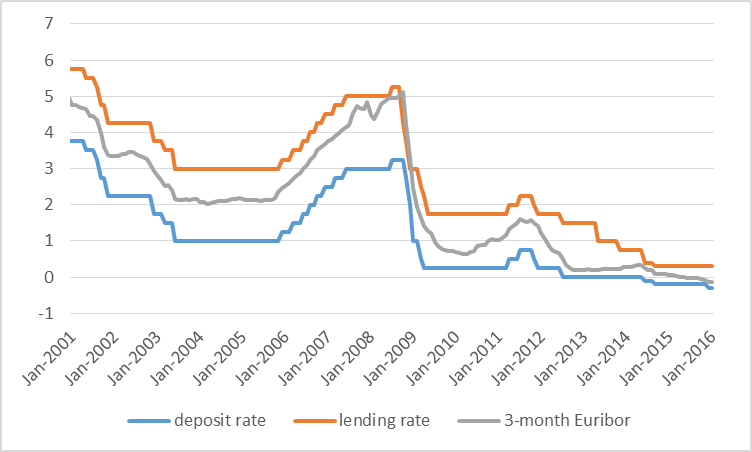

I’ll illustrate how negative interest rates can work by taking the European Central Bank as an example. Traditionally the ECB would set two interest rates: a deposit interest rate that the ECB pays to banks on excess reserves held overnight in the banks’ accounts with the ECB, and a marginal lending rate at which banks could borrow overnight from the ECB. The deposit rate would usually set a lower bound on the interest rate at which banks would offer to lend to each other– why would I lend to another bank at 2.5% if I can get 3% on my ECB deposits, which are in effect an overnight loan from my bank to the ECB? The lending rate likewise sets a ceiling– why borrow from another bank at 5.5% if the ECB will give me all I want at 5% through their lending facility? The graph below shows how this system worked historically, with the interest rate on 3-month loans between banks moving within the corridor specified by the ECB.

Average interest rate over the month on 3-month interbank loans (in gray) and end-of-month values for ECB deposit rate (in blue) and lending rate (in orange), January 2001 to January 2016.

The ECB brought its deposit rate all the way to zero in July 2012. When that didn’t seem to be enough, they went to -0.1% in June of 2014, in other words, charging banks a fee (corresponding to a 0.1% annual rate) on their deposits held in excess of requirements. By last December the ECB had brought the deposit rate down to -0.3%. Here’s a more close-up view of the most recent data. It has functioned just like the historical system, with banks lending to each other at a rate that is somewhere between the deposit rate (currently -0.3%) and lending rate (currently +0.3%). The average rate on interbank loans for January turned out to be -0.15%.

Average interest rate over the month on 3-month interbank loans (in gray) and end-of-month values for ECB deposit rate (in blue) and lending rate (in orange), January 2012 to January 2016.

Why would I pay another bank for the privilege of letting me lend money to them? It’s actually an easy call. If I keep the money myself, I’ll have to pay the ECB 30 basis points interest at the end of the day. If I lend the funds to another bank, those deposits become their problem, not mine. Paying 15 bp to another bank to take them off my hands is obviously a better deal than paying 30 bp to the ECB.

But why would my counterparty agree to the deal? It’s actually the same reason that the interbank rate traded above the deposit rate in normal times. Whether I pay interest or receive interest on my deposits with the ECB, these accounts are useful in their own right for a number of other reasons. Banks use them to make or receive payments from other banks throughout the day, and I never know for sure whether I’m going to end up with more than I need. Another dollar in deposits could well end up costing me another 30 bp, but given other benefits of having the deposits, the true opportunity cost is more like 15 bp.

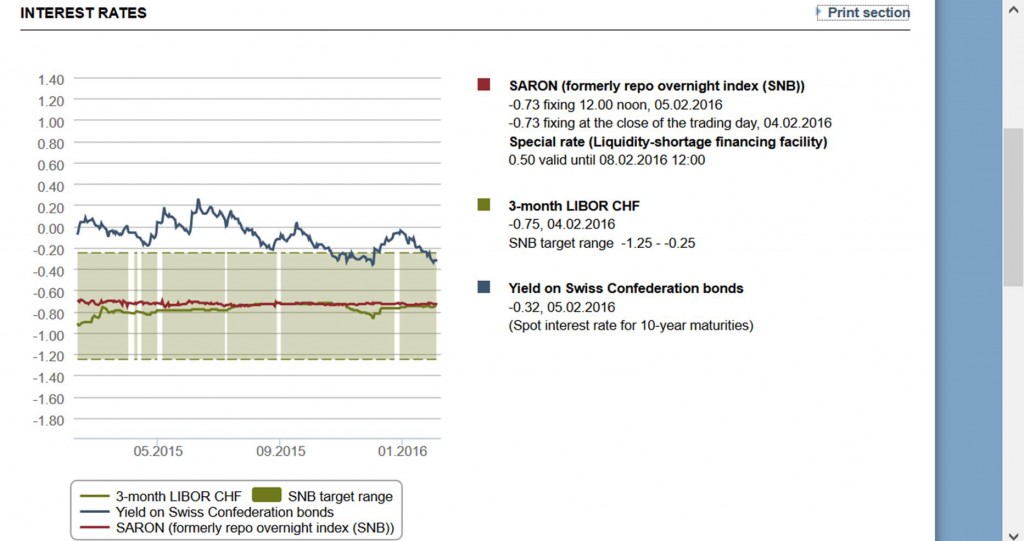

What are negative interest rates supposed to accomplish? Lending deposits overnight to another bank isn’t the only way I could try to get rid of them. Another thing I could do is buy a government security (another very low-risk option for my funds), paying for it by sending my ECB deposits to some other bank. That again would make the ECB deposit fee the other bank’s problem, not mine. If the government security pays positive interest and ECB deposits pay negative interest, the trade is again a no-brainer. But as all the banks try to buy the securities from each other, they will bid up the price of government securities above par. The result is that the effective interest rate on those government securities will go negative as well. In Switzerland, where the Swiss National Bank has moved its policy rate all the way down to -0.75%, the interest rate on 10-year government bonds is now -0.32%.

Source: Swiss National Bank.

The same kind of arbitrage should bring all interest rates including those on riskier securities down, though not necessarily into negative territory. The hope is that by making it cheaper to borrow, more spending and investment by consumers and firms would be encouraged.

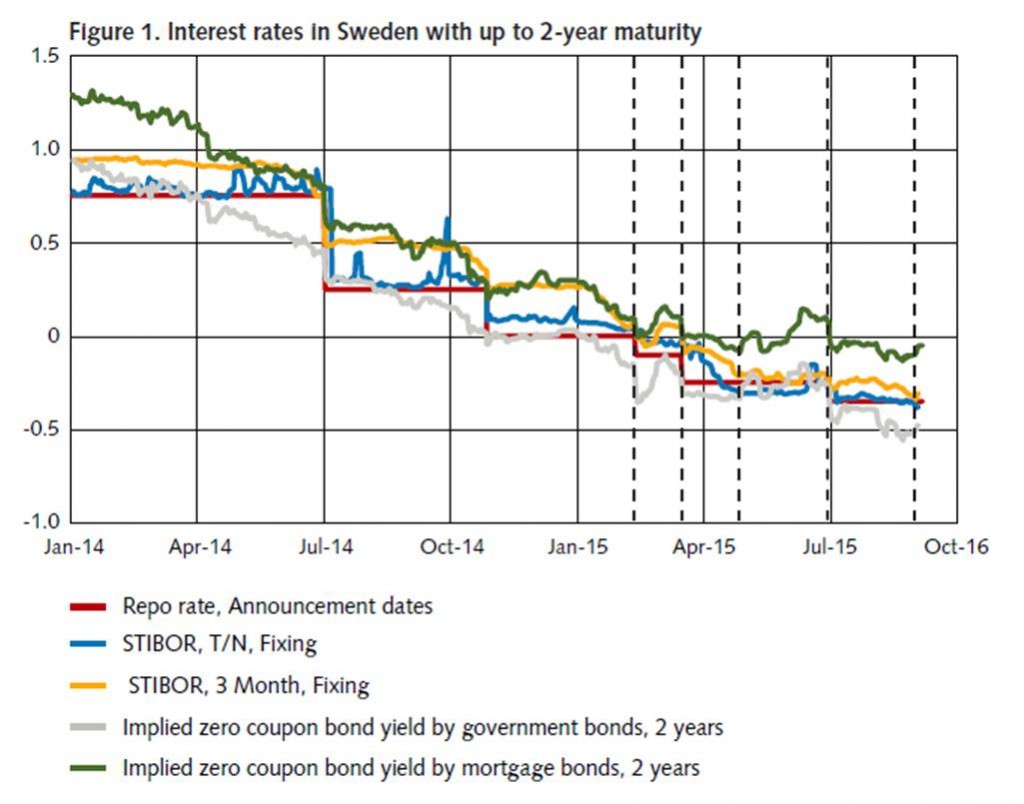

Source: Economic Commentaries, Nov 2015.

A bigger economic stimulus may come from the exchange rate. When safe interest rates are negative in Europe and positive in the United States, investors around the world are going to want to shift their holdings out of euros and into dollars, depressing the euro’s value. A cheaper euro may encourage European exports, which again could be a way to boost economic activity in Europe.

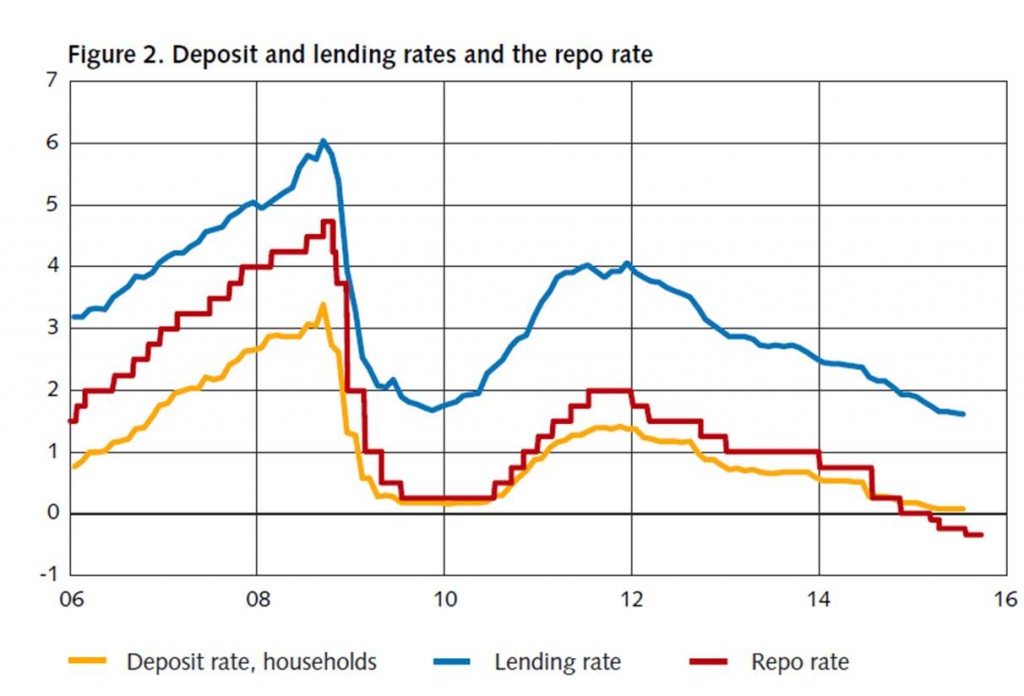

Other issues come into play if the negative yields start to spill over into retail deposits. Banks are understandably reluctant to charge customers to deposit in the bank. For example, in Sweden retail deposits historically paid a lower rate than the central bank’s policy rate. But today customer bank deposits are still paying token positive interest despite the negative rates in the interbank market.

Source: Economic Commentaries, Nov 2015.

Are you willing to pay each month for the privilege of having a checking account or a money-market fund? Given the conveniences associated with both, the answer for many people might be yes. But the bigger the fee becomes, the more you would look for some other form to hold assets, such as cash itself, whose interest rate is never going negative. If cash is too inconvenient, you might start paying somebody to hold the cash for you, at a lower cost to you than the negative-interest money-market fund, but at a positive spread to the money changer, who pockets your fee in exchange for simply hoarding cash in a vault for you somewhere until you want to use your funds. Cecchetti and Schoenholtz explain:

Suppose, for example, that banks were to offer customers the ability to convert their deposit accounts into “cash reserve accounts” (CRAs) that only hold currency. Like the sweep accounts banks created in the 1990s to minimize reserve requirements, CRAs would minimize the holding of central bank deposits. The funds would be available just like a checking account during the business day, but would be swept into cash currency rather than being held as reserves at the central bank. Overnight, the piles of currency belongs to customers, during the day they are the asset balancing the CRA liability on the bank’s own account. Critically, the cash in the bank’s vault assigned to the CRAs is not available to be lent out….

There may be some legal or regulatory impediments to a chartered bank creating CRAs. If that is the case, as it was with the MMMFs, we expect that some clever lawyers will find a way to create a nonbank subsidiary to do it. Or, as has been suggested, maybe an exchange-traded fund.

All of this leads us to conclude that the sustainable lower bound on nominal interest rates is the marginal cost of supplying CRAs.

Allowing funds to flow out of traditional bank accounts and money-market funds into alternative cash-based schemes would be costly and destabilizing. And having real resources devoted to hoarding cash on behalf of depositors rather than seek useful physical investment opportunities would seem to defeat the whole purpose of the measures. When Reserve Primary Fund “broke the buck” on September 16, 2008 (customers’ money-market accounts became worth less than 100 cents on the dollar), it triggered an outflow from other money-market funds that in some ways resembled a bank run. The Federal Reserve was forced implement emergency measures to restore an orderly market. The benefits of another 25-50 bp in stimulus that negative rates could get us are small and, in the case of the U.S. Federal Reserve, seemed to be outweighed by the costs.

But the fact that so many of our trading partners are going negative means that a little interest rate hike in the U.S. goes a long way. As a result of the Fed’s decision to raise interest rates off the zero floor in December, the fed funds rate has recently been trading around 38 bp and 3-month U.S. Treasury bills have been paying about 32 bp. Not much, but significantly better than having to pay for the privilege of lending to your government as is the case in some of our trading partners. That difference between U.S. and foreign interest rates has been a big factor in the surge of the value of the dollar. Cheaper import prices help keep U.S. inflation down, and a strong dollar also discourages U.S. exports and encourages U.S. imports. The change in U.S. net exports in 2015:Q4 subtracted almost half a percent from the quarter’s annual GDP growth rate. If what the Fed wanted with its little rate hike was less inflation and slower GDP growth, it must have been pleased with the results.

I do not expect the U.S. to follow other central banks in driving interest rates negative. But the fact that other countries are going negative while we are not means that the Fed got an unusually big kick out of that little 25 bp move in December. For this reason, it may take some time before we see another move up by the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Disclosure: None.

Nice article. Certainly interbank lending arbitrage seems to be desperation. And negative rates are not pushing inflation up so far.