M-M-M-My Kuroda: What The BOJ Is Up To

Last Friday, Bank of Japan's president, Haruhiko Kuroda, announced that the BOJ will institute negative interest policy to encourage banks to lend, in what I consider to be a desperate attempt to boost Japan’s economy. A negative interest rate will be applied to a “portion” of funds banks have on deposit at the BOJ. An interest rate of 0.01% will be applied to other holdings. The BOJ also announced that it will maintain its 80 trillion yen ($666 billion) a year in government-bond purchases.

Risk asset markets rallied on the news of more central bank (spiked) punch. However, I doubt that negative interest rates will do much, if anything, to meaningfully stimulate Japan’s economy. It is not the supply of credit which is Japan’s main problem. It is the demand for credit. It is true that Japan’s two-decade-long malaise was caused, in part, by poor credit supply.

Following Japan’s boom of the late 1980s, Japan’s banks were saddled with bad debt. Since there were little efforts by Japan’s policymakers to resolve banking system problems, these so-called zombie banks were unable or unwilling to lend as they had before. During the next two decades, Japanese consumers adapted to life without easy access to credit. The response by Japan’s policymakers was to continually lower interest rates. However, this did not do much to boost lending as Japan’s banks were still unwilling or unable to lend. Instead, Japan’s financial institutions simply borrowed on the short end and either used the cash to shore up balance sheets or used the proceeds to buy Japanese government bonds (JGBs). This helped to drive down long-dated JGB yields. The resulting lack of inflation from sluggish economic growth also aided in pushing long-term Japanese interest rates lower.

Yield of 10-year JGB since 1990 (source: Bloomberg):

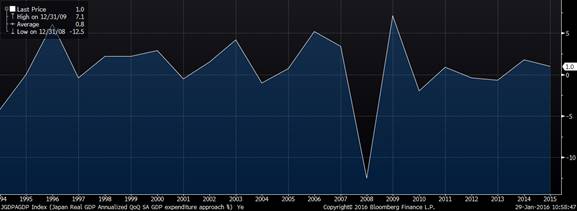

Japan Annualized QoQ GDP since 1994 (source: Bloomberg):

Annual readings of quarter-over-quarter GDP are now the accepted measure of economic growth. Bloomberg data only goes as far back as 1994 for Japan. However, one can see that since 1994, annual Japan GDP has averaged 0.8%. It is little wonder that Japanese interest rates and bond yields have remained low for two decades.

Investors and advisers have been told that monetary policy accommodation is nearly always stimulative for growth. This has been mainly true in the past, but monetary policy tends to work best when economic malaise is due to cyclical phenomena. What Japan is dealing with are structural phenomena. These include an aging population and two generations who consider low interest rates and slow economic growth as normal. Humans are very adaptable. This is how we became the dominant lifeform on the planet. Faced with a dearth of available credit, low interest rates and modest inflation, Japanese consumers altered their lifestyles and expectations accordingly. Thus, low rates and (potentially) a greater supply of credit will probably do little to boost economic activity, in the long run.

Low inflation or deflation can also have debilitating effects on consumption and growth. That prices are not rising appreciably reduces the urgency for consumers to make purchases. Because inflation and incomes are not rising appreciably, purchasing goods using credit could be seen as disadvantageous. One of the perceived benefits of purchasing with credit is that one can borrow in today’s currency and repay in tomorrow’s lower-valued currency (thanks to inflation). Healthy inflation also usually lowers consumers’ effective debt load as wages often correlate closely to inflation pressures.

In the absence of fiscal reforms and demographic changes, the BOJ has few tools remaining. However, at the present time, the BOJ might be effectively trying to loosen a nut with a hammer. One might be hopeful that central bankers can jar the economy loose from its malaise. They could also merely mangle it, making it more difficult for fiscal policies to repair an economy, if better fiscal policies are implemented at a later date. At the present time, I believe that central banks’ (around the world) abilities to engineer a return to prior levels of economic vibrancy are scant. Demographics, technology and globalization are driving economies. Central bankers can do little to combat these forces. The question that I think will be asked more frequently in the near future is: Should central bankers combat these structural forces?

Disclosure: None.

Disclaimer: The Bond Squad has over two decades of experience uncovering relative values in the ...

more

Do you think central bankers should combat these structural forces? Why shouldn't they?

It is not whether or not they should. It is whether they can. Central banks have cyclical tools. I.E they can encourage more aggressive lending, borrowing and/or investing. The cost of capital is not the problem. Structural demand for credit is. The Fed has a very string hammer, but it is of little use when the problem is a screw.

Nice comment thread, thanks.

Thanks for the informative and well-written article, Tom. With the propensity for Central Bankers to do the heavy lifting these days, there's no incentive for governments around the world to implement any kind of stimulative fiscal policies. This kind of head-in-the-sand approach by world leaders will do nothing, in the long run, to foster trust in the markets...we may see a hard landing at some point in the not-too-distant future where no country can be immune from its fallout, IMHO (I hope I'm wrong, though).

Agreed, but the Fed lifted heavily during WW2 and can lift again if it wants to do so. I just don't think it wants to.

Agreed, I actually just read an article by you about that which I thought was quite good: www.talkmarkets.com/.../the-federal-reserve-financed-ww2-but-cannot-finance-america-now

Yes, Charles, I always argue that the Fed is about bonds and banks. It used to be about the USA in WW2. I hope there are not dark reasons for that change of attitude. I really do.

The Fed is not only out of tools, it does not should not have the right tools. Headwinds to growth are mainly structural in nature. Fiscal policy mist be changed to increase per capita consumption without encouraging or requiring large sums of household debt.

Is the world the same place now as it was then and would that tool be just as effective (economically, sociologically, technologically, etc.)?...no doubt, lots of factors to consider.