Japan: The Future Is Now

Image Source: Pixabay

During my working life, I saved a large share of my income—too large in retrospect. (I didn’t know that old people place far less value on consumption than young people.) Nonetheless, some saving was appropriate so that I’d have assets to fall back on when I was too old to work. The Japanese seem to have had the same idea.

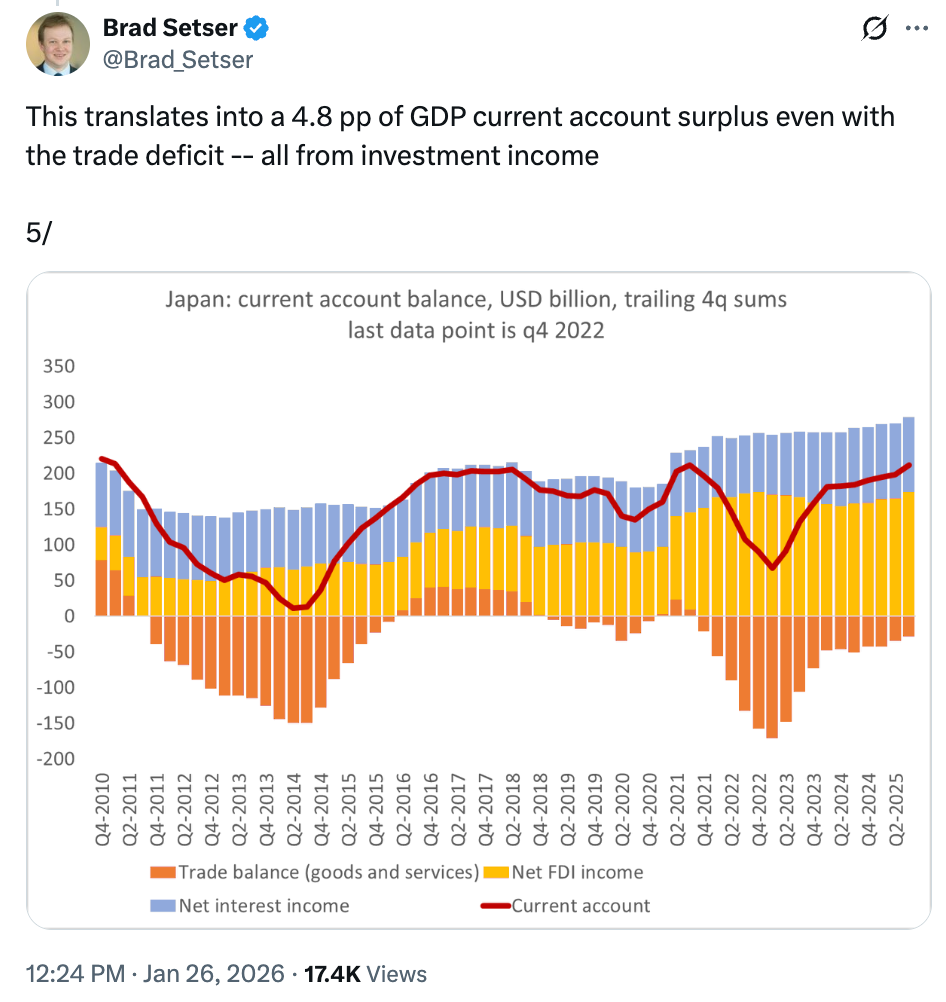

An excellent series of tweets by Brad Setser illustrates how Japan has accumulated a formidable stock of foreign investments:

When students used to ask me about the US trade deficit, I pointed to several possible outcomes.

-

The bad news is that our recent trade deficits may lead to future trade surpluses.

-

The good news is that we might end up running trade deficits forever.

This tended to confuse students, as the media treat trade deficits as a bad thing and trade surpluses as a good thing. Why should we worry about the danger of future US trade surpluses?

You can think of a trade surplus as Americans working hard to produce goods and services that get to be consumed by foreigners. That doesn’t sound much fun!

When I was young, the Japanese worked hard to produce lots of useful stuff that Americans like me got to enjoy. They took the proceeds from these exports and accumulated a lot of foreign assets, including both financial assets such as stocks and bonds and direct foreign investments such as Toyota factories in Kentucky.

Today, Japan has an aging population. You might say the entire country is shifting toward retirement. As time goes by, an increasing share of Japanese consumption is goods that are produced by labor in foreign countries with younger populations. Japan has accumulated enough foreign assets to fund a portion of consumption equal to roughly 5% of GDP.

[This figure is derived by combining their current account surplus of 4.8% of GDP and their trade deficit of around 0.4% of GDP.]

To be clear, Japan is not yet relying this heavily on foreign goods. Their trade balance is negative but relatively small. Most of the current account surplus is being used to accumulate still more foreign assets in anticipation of an even older population in the years ahead. Sort of like an old miser that keeps re-investing his 401k dividends at age 70. (And who might that be?)

For many people, the idea of future US trade surpluses seems implausible. We’ve been running trade deficits for many decades, and it seems like nothing will ever change. How can I be sure that our current trade deficit will lead to future trade surpluses? In fact, I am not certain that this will occur—it is quite possible that the US will never end up paying for our recent trade deficits with future exports of goods and services. Perhaps we’ll end up paying in some other way. But what might that be? How else could we pay for all the goods that countries keep sending us?

I see at least four possibilities:

-

Profits earned by US multinational businesses.

-

The “export” of real estate.

-

The importation of people (immigration).

-

Implicit debt default via inflation.

America’s corporate sector increasingly dominates the global economy. Thus it seems possible that our corporate sector might earn enough profits on overseas business to fund our trade deficit—enough to pay for the difference between the goods we export and the goods we import.

When a foreign business owner sells goods to the US, they are paid in dollars. They might choose to take those dollars and buy some US real estate, say a large home in Orange County. In that case, you might say we’ve “exported” the home to a foreigner, but it’s not viewed as an export because the house and land never actually leave the US. In contrast, when Japanese tourists visit Disneyland, the expenditure is viewed as a service export, even though the service occurs within the US. Go figure.

Alternatively, a foreign business owner holding US dollars might immigrate to America, bringing their dollar claims with them. In that case, the US government still owes a debt to the bond holder, but it’s no longer a foreign debt. It is a obligation to pay money to someone who is now an American citizen.

And finally, the US government might inflate away much of our national debt with an expansionary monetary policy. In that case, the Treasury bonds accumulated by foreign exporters would have far less purchasing power than anticipated, perhaps less that the value of the US held assets of foreign countries.

All these hypotheticals increase the probability that the US never actually pays for its trade deficit with future exports.

Many people find it hard to imagine that the US might eventually begin running trade surpluses. But the Japanese case suggests that we should not rule out the possibility that our trade balance might flip in the future. It did for Japan. For the Japanese, the future is now. They are already living in the “long run”, the world where the trade balance has reversed, just as economic theory predicts. It would not surprise me if the same thing happened in the US, but of course in the opposite direction—from trade deficit to trade surplus.

My own view is that the US is not like Japan, and that the four hypotheticals above will be sufficient to prevent the US trade balance from moving toward surplus. I expect that some combination of multinational profits, real estate sales, immigration and debt default via inflation will be sufficient to kick the can down the road for at least for another 50 years. But that’s just a hunch, and no one should put much weight on my prediction.

According to AI Overview, China has a negative balance in investment income, despite a massive net surplus in foreign assets:

As of mid-2025, China maintains a massive net international investment position (NIIP) with a net asset surplus of approximately USD 3.8 trillion, yet simultaneously reports a consistent deficit in its primary investment income balance (investment earnings). While external assets totaled over USD 11 trillion, the returns on foreign investment in China (liabilities) historically exceed the returns on Chinese investments abroad (assets), primarily due to higher-yield inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

China presumably holds fewer high return American equities than Japan, and more low return Treasury securities. As a result, China’s current account surplus is smaller than its trade surplus. (Brad Setser suggests that China’s current account surplus is larger than shown in the official data, but still smaller than its trade surplus.) Unlike Japan, China is not ready to “retire”.

In 2024, Germany had a current account surplus of 5.7% of GDP, even larger than Japan’s surplus. But unlike Japan, Germany had a roughly comparable trade surplus (goods and services). This may reflect that fact that the Germans are known to be cautious investors, and perhaps they have earned smaller investment returns than the Japanese on the foreign assets they’ve accumulated from export earnings.

When trying to explain trade balances, mercantilists in Washington greatly overrate the importance of things like “low wages” and underestimate the importance of the investment sector. Low wages do not explain why Germany has a big trade surplus while Japan runs a deficit, indeed German wages are roughly 75% higher than Japanese wages. Rather, Japan seems to have earned greater returns on its foreign assets. The investment account drives the trade account.

[For the Germany/Japan wage comparison you do not want to use PPP wages, which are 40% higher in Germany than in Japan. You need nominal wages in a common currency. Due to factors such as taxes, comparable wage data is hard to find, but the huge 75% gap in the link above suggests than German wages are clearly higher.]

More By This Author:

A Liz Truss Moment?Which One Doesn't Belong?

The Nguyens And The Fed