How Coronavirus Hits Global Economy And Affects Monetary Policy

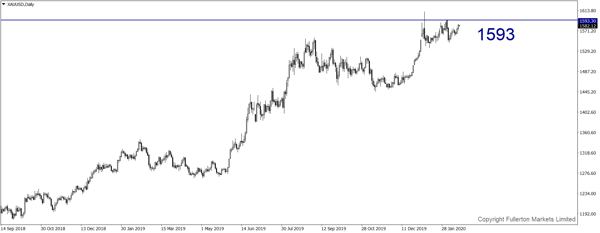

With uncertainties weighing on the global economy, long gold at dip.

Latest update: China said the number of coronavirus cases climbed above 70,000 as the province at the epicentre of the outbreak reported 1,933 new cases, slightly higher than a day earlier. The head of a Wuhan hospital said a turning point has been reached as new cases fell over the weekend, but the outlook was more cautionary outside of China. The head of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases said the outbreak is on the verge of a global pandemic if containment steps fail to show more success.

Deaths were reported in France and Taiwan over the weekend, bringing the number of fatalities outside mainland to five. The US evacuated some passengers from a cruise ship in Japan, where 355 people have the coronavirus.

Watch the eurozone PMI for any possible signal

Growth in much of the eurozone economy has been sluggish in recent years. Now, the export-dependent bloc has to deal with the economic fallout from the deadly coronavirus. On Friday, IHS Markit will release composite purchasing managers’ indices — that combine manufacturing and services activity — for the eurozone and its two biggest economies, France and Germany. These will provide a snapshot as to how the region’s companies are faring and could offer an early clue as to how severe the impact will be.

January’s reading for the eurozone hit a five-month high, suggesting an upturn in the bloc’s fortunes, but February’s survey will give a much better picture of any fallout from China’s shutdown. With inflation stubbornly low and growth still particularly weak in Germany, the European Central Bank cut rates and restarted its controversial bond-buying programme last year. However, opinion is divided as to whether this monetary loosening will have much of a positive effect, particularly given how much stimulus the ECB has already injected. Industrial production data last Wednesday offered little comfort. It showed a 2.1% fall in the eurozone in December, and a 4.1% drop for 2019.

Worries over the spread of coronavirus have boosted the dollar, a safe haven for investors during uncertainty over the global outlook. The dollar index, which measures the greenback against a group of other currencies, was up 0.2% in the same period, bringing its gains over the past month to 1.8%.

The double hit of the coronavirus and disappointing economic data sent the euro to its weakest level in almost three years last week. Meanwhile, IHS Markit will also publish a PMI for the UK on Friday. While economic growth has also been lackluster, partly driven by uncertainty over its exit from the EU, the UK enjoyed an unexpectedly strong bounce in its PMI in January following the landslide election victory by Boris Johnson’s Conservative party.

Will Fed remain on hold throughout 2020?

On Wednesday, minutes from the Federal Reserve’s latest policy-setting meeting will be released. In January, the US central bank stood firm and left its main policy rate unchanged at a range of 1.5 to 1.75%. Chairman Jay Powell underscored at the time that the US economy remained “in a good place” and that officials had not altered their plans to leave interest rates where they were until the end of the year.

Still, market participants took certain comments to be dovish, sending Treasuries rallying. Investors seized on Powell’s disclosure that the Fed is “not satisfied” with inflation running so persistently below its 2% target given the length of the current US expansion. Moreover, Powell’s warning about the potential impact of the coronavirus outbreak on economic growth further reinforced investors’ perception that the Fed might find itself cutting interest rates once again in 2020.

According to data compiled by CME Group, expectations for a quarter-point cut as early as July have risen in recent weeks, one meeting earlier than what traders were expecting at the start of the year. Wednesday’s minutes will give further clarity as to where central bank officials stand on these issues, and if either inflation or China’s health crisis will change the US economic outlook by a sufficient degree to justify further easing. In his testimony to Congress last week, Powell said it might be too early to tell how much damage, if any, the coronavirus would inflict on the US economy. For now, Powell says it’s too uncertain to even speculate, as they will be looking at the economic data.

After a two-day meeting in Washington, the members of the Fed’s Open Market Committee left the federal funds rate at a range of 1.5 to 1.75%. They made only one change to their policy statement, describing growth in household spending as “moderate,”rather than “strong,” as they had in December. This continuity suggested that the committee still sees the economy as “in a good place,” as Chair Jay Powell often puts it, and that they have not changed their plan to leave the policy rate where it is through the end of this year.

Even though it left the Fed’s main policy rate unchanged, the committee raise the interest it pays banks on the reserves they hold on the Fed’s balance sheet, from 1.55% to 1.60%. This “interest on excess reserves,” or IOER, is one of a few short-term interest rates the Fed uses as a tool to keep the fed funds rate within its target band. But Powell said at his press conference that they will continue to adjust that after the decision.

Ultimately, what Fed is trying to do is deliver a federal funds rate that's well within the range. IOER is just a tool to do that. Markets took some of Mr Powell’s press conference comments to be dovish, notably a statement that the coronavirus outbreak could affect growth and a reiteration of the Fed’s concern that US inflation has been under target.

The coronavirus outbreak posing a substantial downside risk to Chinese growth and the global economy more broadly, the Fed could very well provide additional accommodation. But for Fed rates, we think cuts are more likely than hikes. In September, the federal funds rate had spiked briefly above the Fed’s target band, helping to spur a series of quick shifts by the central bank, most significantly a decision to expand its balance sheet.

It bought Treasury bills at a rate of $60 billion a month, and in turn credited banks with reserves. This raised the overall level of reserves available to financial markets and eased the pressure on short-term interest rates. The Fed also lowered the rate of interest it paid on those reserves at a faster rate than they normally would have for policy shifts, to further help drag the policy rate down into its target band. Now, with that rate sometimes dipping below IOER, the Fed is increasing the interest it pays, to drag the fed funds rate back up toward the middle of that band.

The move indicates that the Fed’s decision to push reserves back into the financial system is working. Policymakers have not committed to an overall reserve level, saying that they wished to return to where they were before the spike in short-term interest rates, and that they would likely continue expanding the balance sheet into the second quarter of this year.

In his press conference, Mr. Powell pointed out that market demand for reserves can be volatile, particularly during tax season, when the US Treasury takes payments from companies, moving reserves out of financial markets and into Treasury’s account at the Fed. Fed needs reserves at all times to be no lower than they were in early September, around $1.5 trillion. Treasury’s balance at the Fed has swung between $130bn and $400bn over the past year, so a cushion on top of that floor could bring levels as high as $1.9 trillion, from $1.6 trillion now.

Powell said the Fed believed it would reach an “ample” reserve level in the second quarter of 2020. The proposed reserve floor feels suspiciously round, and this is not a precise estimate of where the kink in reserve demand is. They just want to get back to a safe place. In addition to responding to disruptions in short-term interest rates, the Fed has spent the last year in a review of how it carries out and talks about monetary policy. With policy rates already close to zero, the Fed is concerned about the tools it will have to hand, should a recession come.

In January, Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke, both former Fed chairs, warned that the central bank might not be able to handle a downturn alone, and asked Congress to consider responding with more spending.

Normally, in January, the Fed would publish changes to its statement on its longer-run goals and strategy. This year it has opted to postpone those changes until it completes its review. As is normal for the new year, the committee swapped in four new regional Fed presidents as voting members.

Commodity will serve as a leading indicator to gauge the virus’ development

The outbreak of coronavirus brought copper’s rally to an end. After rising at the end of last year on anticipation of a preliminary trade deal between the US and China, the metal, often viewed as a bellwether for the global economy because of its wide range of uses has fallen sharply on fears of the demand hit from the deadly virus. The metal, used in everything from household wiring to electricity transmission cables, hit $6,300 a tonne in mid-January before dropping to a near three-year low of $5,528 a couple of weeks later as the scale of the health crisis started to become clear. It is now trading at more than $5,700 a tonne.

Copper smelters had been running at close to normal levels since the outbreak because they were not easy to shut down and restart. But fabricators, which machine, cut and weld alloys to turn them into products, have been running below 50% capacity, forcing the smelters to build inventories or send refined copper to warehouses. As China returns to work following the lunar new year holiday, the impact of the virus on the copper market should become clearer. Big producers Antofagasta (ANFGF) and BHP (BHP) could provide some guidance when they release corporate earnings in the coming week. But, as with other commodities, what is needed most to push prices substantially higher is signs of the virus coming under control.

Policy easing, not fundamentals are driving the stocks’ rally

The coronavirus outbreak has closed factories, curbed spending and disrupted supply chains in the world’s second-largest economy. But US stocks have held close to records. The market’s resilience stands in contrast to how quickly the epidemic has spread and how difficult it has been to assess the accuracy of information coming out of China. We have to remember that stock markets are not particularly good at pricing in these types of risks. Much of the market’s rebound appears to have been fuelled by relief over Chinese officials unleashing a wave of spending to help relieve the pressure on the Chinese economy.

The People’s Bank of China deployed 1.7 trillion yuan in open-market operations on February 3 and 4. Not coincidentally, many global stock indexes bottomed out around then. The Shanghai Composite rose every single trading day from February 4 to Wednesday, logging its longest streak of consecutive gains in more than a year. The S&P 500 has also pared losses, closing Friday up 4.6% for the year and at a record.

Evidence that Beijing is willing to roll out further stimulus has been reassuring to many money managers, especially since the fate of the global economy has become intertwined with that of the Chinese economy. China accounts for almost a fifth of global domestic product when adjusted for incomes, according to the International Monetary Fund, meaning slowdowns there have the potential to cast a pall over the rest of the world.

US Treasuries to tell a “true story”

Those who worry the market’s rebound might not be on the sturdiest ground cautioned that such projections will assume that the outbreak will be contained in the coming months, that central bank stimulus will be enough to offset a slide in manufacturing activity and spending, and that the trajectory of the current coronavirus epidemic will be similar to prior outbreaks. Those assumptions might not necessarily turn out to be true. On the other hand, the US Treasury Department sold 30-year bonds at a record low yield on Thursday, highlighting investors’ demand for longer-term debt and its benefits to the government.

Fear that the coronavirus will slow global growth has helped push down Treasury yields in recent weeks. Other factors include persistently soft inflation, which has limited one of the main threats to the value of longer-term Treasuries. Investors have also grown more comfortable buying 30-year bonds because they view them as insurance against losses in riskier assets. Prices of 30-year bonds increase more for every one-percentage-point decline in yields than those of shorter-term bonds. That means on days like Thursday when investors are selling stocks and buying bonds, the holders of 30-year bonds are well-hedged.

Still, last Thursday’s level doesn’t represent the lowest point that the 30-year bond yield has ever reached. Last August, it settled as low as 1.941%, but yields rose again before the next 30-year auction in September.

In recent years, low Treasury yields have, at times, caused US officials to flirt with issuing bonds with maturities beyond 30 years to lock in low-interest rates for a longer period.

Buying gold at dip

Market may increase the betting central banks to step in this year, after the coronavirus heavily disrupted global growth activities and supply chains.

During the holiday-shortened week ahead, there’s little in the calendar of events that looks likely to pull investors away from virus headlines. The impact of the virus on the global economy is going to be significantly more than what people are expecting, and when the global economy goes slow the Fed steps in.

Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee’s January 28-29 meeting, to be released Wednesday, cover a period in which policy makers were still monitoring the virus originating from China.

A more real-time view – Treasuries trading from the past few days – shows market participants worried about the economy’s prospects. A flight-to-quality move ahead of the three-day weekend drove the widely watched spread between two- and 10-year yields to the flattest level since November.

Data shows money managers have increased their bullish gold bets by 17,876 net-long positions to 229,369, weekly CFTC data on futures and options show. As long as the perspective on the global economy remains uncertain, gold uptrend started from December looks still intact.

Our Picks

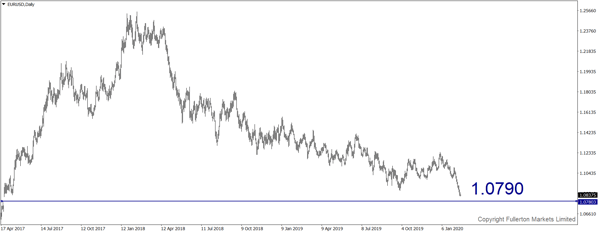

EUR/USD – Slightly bearish.

This pair may drop towards 1.0790 this week.

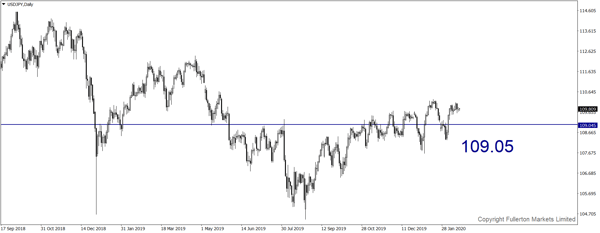

USD/JPY – Slightly bearish

This pair may drop towards 109.05.

XAU/USD (Gold) – Slightly bullish.

We expect price to rise towards 1593 this week.

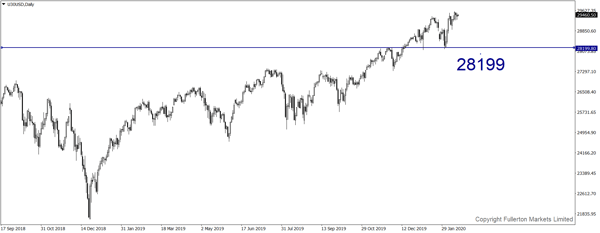

U30USD (Dow) – Slightly bearish.

Index may fall towards 28199 this week.

Disclosure: Trading foreign exchange on margin carries a high level of risk, and may not be suitable for all investors. The high degree of leverage can work against you as well as for you. ...

more