China Posts Some Kind Of Upside

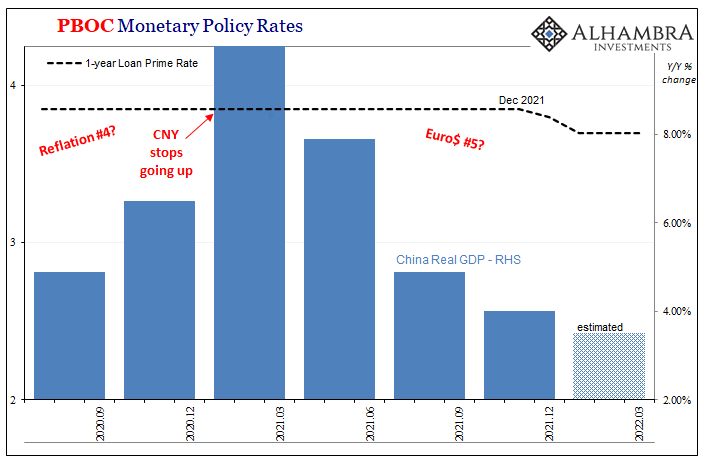

They zig when they were supposed to zag. China’s PBOC was widely expected to drop its MLF rate, triggering the same for bank LPR (loan prime rate) which will be published this upcoming Monday morning (Beijing time). It would have been the third rate cut since December, though it should be noted Chinese authorities had already refrained from action in February, too.

Given the credit data for last month, some kind of monetary policy response seemed all-but-inevitable. Even a former top advisor to the PBOC, Yu Yongding, argued just yesterday in favor of lowering benchmark rates.

China will further cut interest rates to stabilise the economy, as shrinking China-US yield spreads will not change Beijing’s monetary policy loosening bias, the China Securities Journal reported on Monday, citing former central bank adviser Yu Yongding.

At the central bank’s meeting today, however, Chinese policymakers left the MLF unchanged thereby assuring the LPR will remain steady as a result.

What changed between yesterday and today? Or was it February? The headline from China’s NBS earlier today reporting the first of 2022’s economic data might help explain:

The numbers for the Big 3 (industrial production, retail sales, and fixed asset investment) were up all across-the-board; a clean New Year sweep. IP came in at 7.5% year-over-year (all January and February combined), retail sales accelerated to 6.7%, while fixed-asset investment (FAI) the surprise of the bunch rising 12.2%.

The NBS leadership was very pleased, making certain to credit overlord Xi Jinping for the enlarged results:

From January to February, in the face of multiple challenges such as the complex and severe international environment and the spread of the domestic epidemic, under the strong leadership of the Party Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at the core, all regions and departments earnestly implemented the decisions and arrangements of the Party Central Committee and the State Council, and scientifically coordinated the epidemic.

More than anything, “scientifically coordinated the epidemic” at least partly explains these economic accounts. The Chinese have insanely pursued a zero-COVID policy (or have intentionally used this as a cover) which demands periodic regional lockdowns, including several over the final half of last year.

Fewer interruptions in January and February meant the economy being paid back to some extent for activity held back from before; whether this is the planned result of “science” is, of course, another matter. Put that together with fewer especially industrial lags, such as more auto production given semiconductor chips aren’t so hard to come by these days, and China’s economy was ready for an upside.

Just how much of an upside?

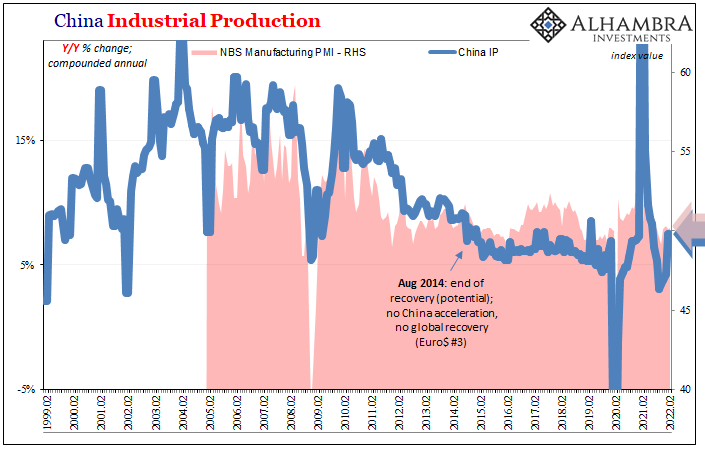

As with all things post-2020 recession, being better than what just happened is almost always misleading. China’s IP, for example, up at 7.5% is a clear improvement from 4.3% in December and continues a rise from September 2021’s low of 3.1%. But for an economy supposedly coming back from repeated artificial intrusions, that’s hardly much of industry making up for lost time.

Seven and a half is what used to count as a floor, today an “upside” and COVID-free bounceback in 2022 which is about level with 2018-19’s globally destructive downturn. And even the NBS’s very own PMI didn’t figure this much (stuck around 50 both months).

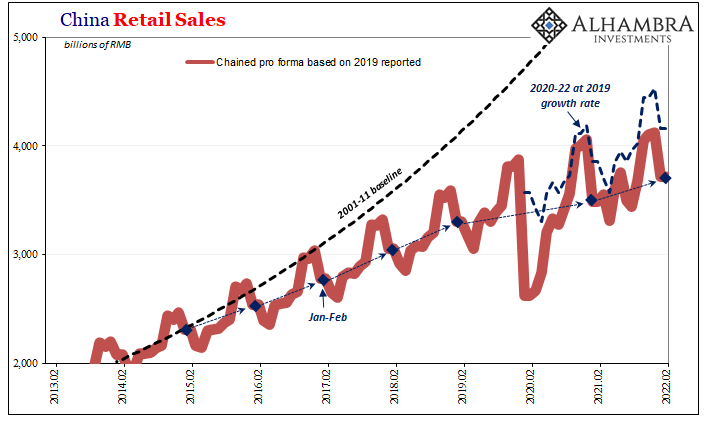

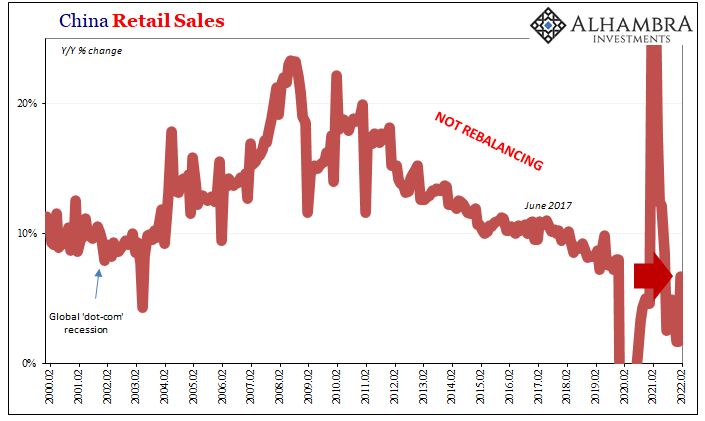

Retail sales might be the clearest example of this shortfall. These had been utterly atrocious all last year for whichever reason(s) you might choose, including those corona policies. It had gotten so bad that the December year-over-year gain was an alarming 1.7%!

Had it been that low because consumers were locked down, then allowed to move about there should’ve been incredible pent-up demand. In January-February 2022, bumping up to 6.7% only appears to be a remarkable improvement, a “scientifically coordinated” achievement bordering on the miraculous (the Communists don’t do miracles, however).

Yet, prior to 2020, retail sales had only been less than 7% just one time back in ’03. Before July 2019, there had never been an 8%. Now, 6.7% deserves one of Xi’s patented Winnie the Pooh smiles.

That’s not a give-back, it’s only managing to revert to the prior downward trend; no upside whatsoever.

When you see that trend for consumer spending in context, what stands out is just how obvious “something” likely fundamental has changed. Even when ignoring the 2020 lows, retail sales haven’t come close to reverting to the troublesome, downturn-like numbers from back in 2018. There’s a new way and it’s somehow substantially less even in its “best” months.

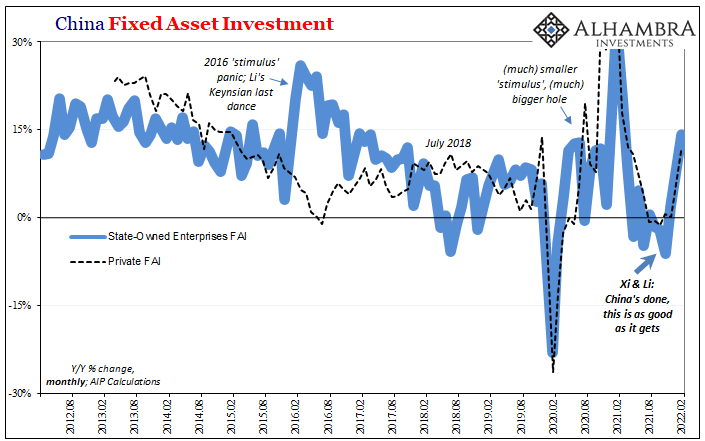

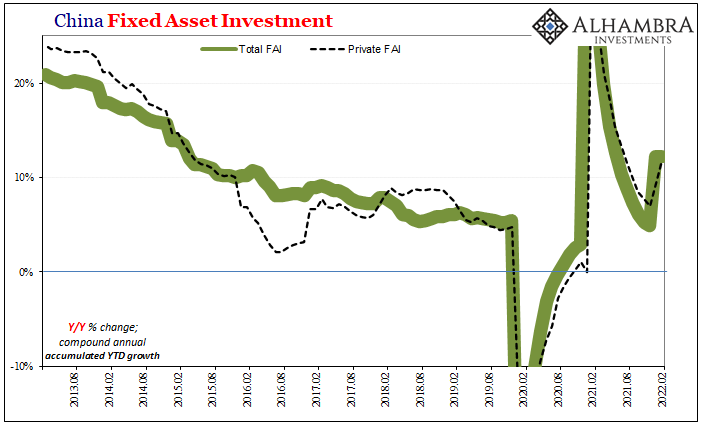

That leaves just FAI as the one statistic which could be genuinely said to have created an upside surprise. Total FAI, again, up 12.2% while private FAI was also double-digits. The fiscal “stimulus” stuff of State-owned investment managed 14%.

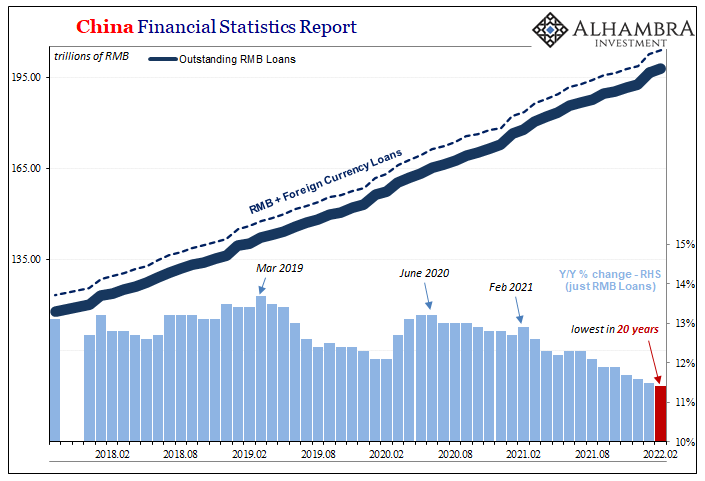

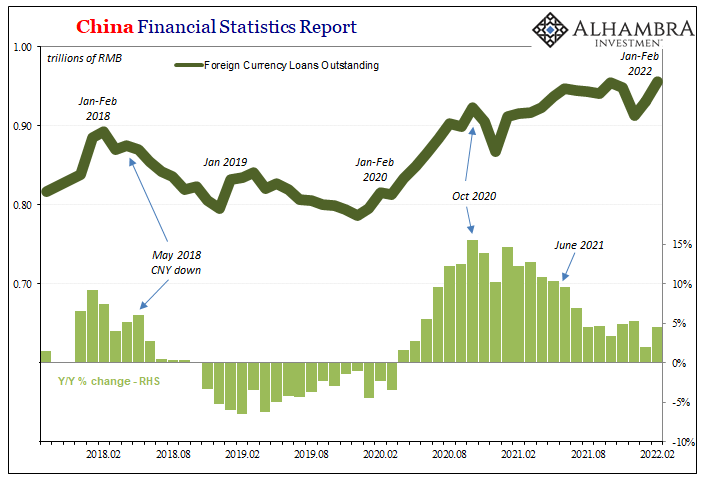

The problem here, though, is the credit/debt numbers; FAI is financed by debt. Those, as usual with China, were front-loaded and still wildly disappointing raising the issue of whether (like 2016 or 2019) actual investment activity will continue forward from February at the same pace without the debt.

Communist China dances to rigid calendar patterns, and with the 100th CCP birthday, there was political pressure to keep things steady for it.

In fact, stability continues to be the overriding theme so far after the last National People’s Congress recently wrapped up. Not only did suddenly-retiring Li Keqiang (that’s another story) use the term frequently in his reports to the NPC, today’s press release from the NBS not coincidentally did the same:

In terms of prevention and control and economic and social development, we have adhered to the principle of maintaining stability and seeking progress while maintaining stability. The national economy has continued to recover steadily, production demand has grown rapidly, employment and prices have generally been stable, new growth drivers have continued to grow, and new progress has been made in high-quality development. [emphasis added]

China’s spokesperson then added, “At the same time, it should be noted that the external environment is still complex and severe, and my country’s economic development faces many risks and challenges.” Two months of this kind of uninspiring COVID-free upside – outside of FAI – speaks plainly about that “external environment” along with “many risks and challenges.”

These figures are all improved from December, clearly, but that just doesn’t quite mean what it may sound like. On the contrary, barely better than the last part of last year is, frankly, more concerning than not.

So, did the PBOC refrain from March 2022 action because the economy, meaning external environment, has surmounted those challenges, or because they’re cognizant of being perceived as being at odds with other central banks’ policies? The timing, both the PBOC and the Fed just a day apart, might better contain the answer.

Even after today’s numbers, or because of what’s really the case with them, mainstream Economists now more strongly expect PBOC rate cuts in April. US markets, too.

Disclosure: This material has been distributed for informational purposes only. It is the opinion of the author and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any ...

more