A Liz Truss Moment?

Image Source: Unsplash

In recent months, long-term Japanese bond yields have increased sharply. Some have compared the situation to the ill-fated Liz Truss government in the UK, which saw a similar spike in government bond yields. Here’s Bloomberg:

The rout pushed yields to record levels, stoked worries that Japan was heading into a “Liz Truss moment” and led US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent to seek reassurances for what he called a six-standard-deviation move.

It’s not hard to see why people might make the comparison, as the new Japanese government is pursuing an expansionary fiscal policy:

The broad causes are in less dispute: Japan’s adjustment to higher inflation, which is pushing up interest rates, is disturbing years of calm in the market. Plans by Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi to pause a sales tax on food and beverages, an apparent bid to shore up support before a snap election next month, are adding to worries about fiscal policy.

Worries about the deficit were also cited in the bond market sell-off during the brief period when Liz Truss headed the British government.

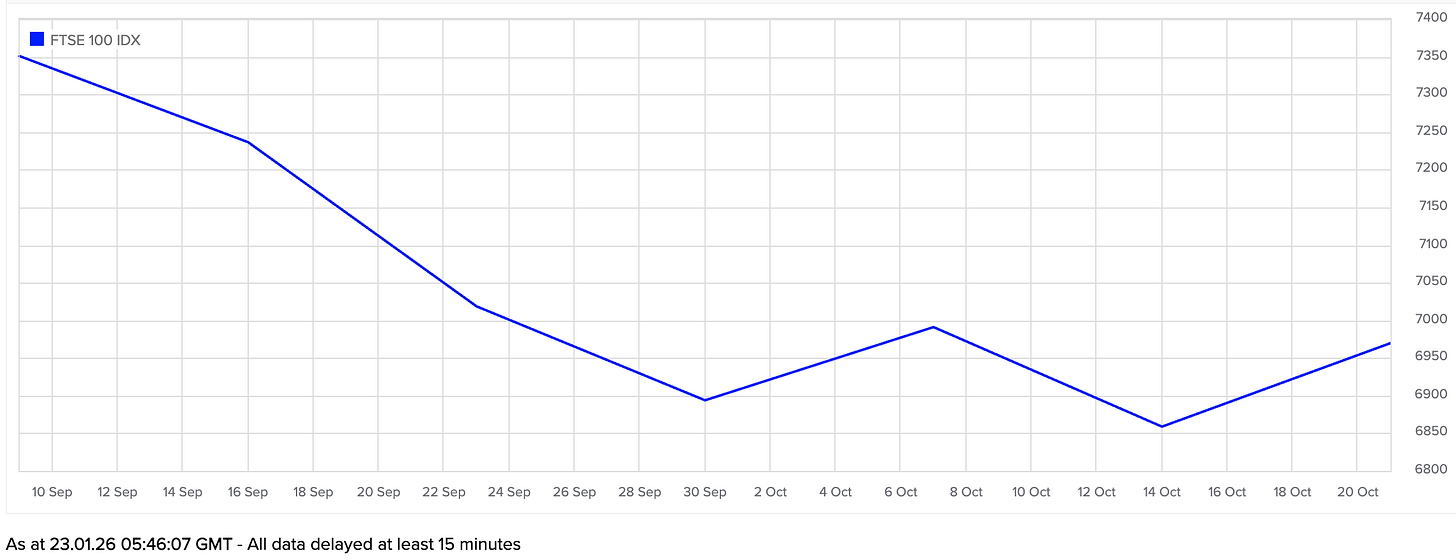

But there are also some important differences. To begin with, stock prices in the UK fell sharply during the six weeks when Truss was in power:

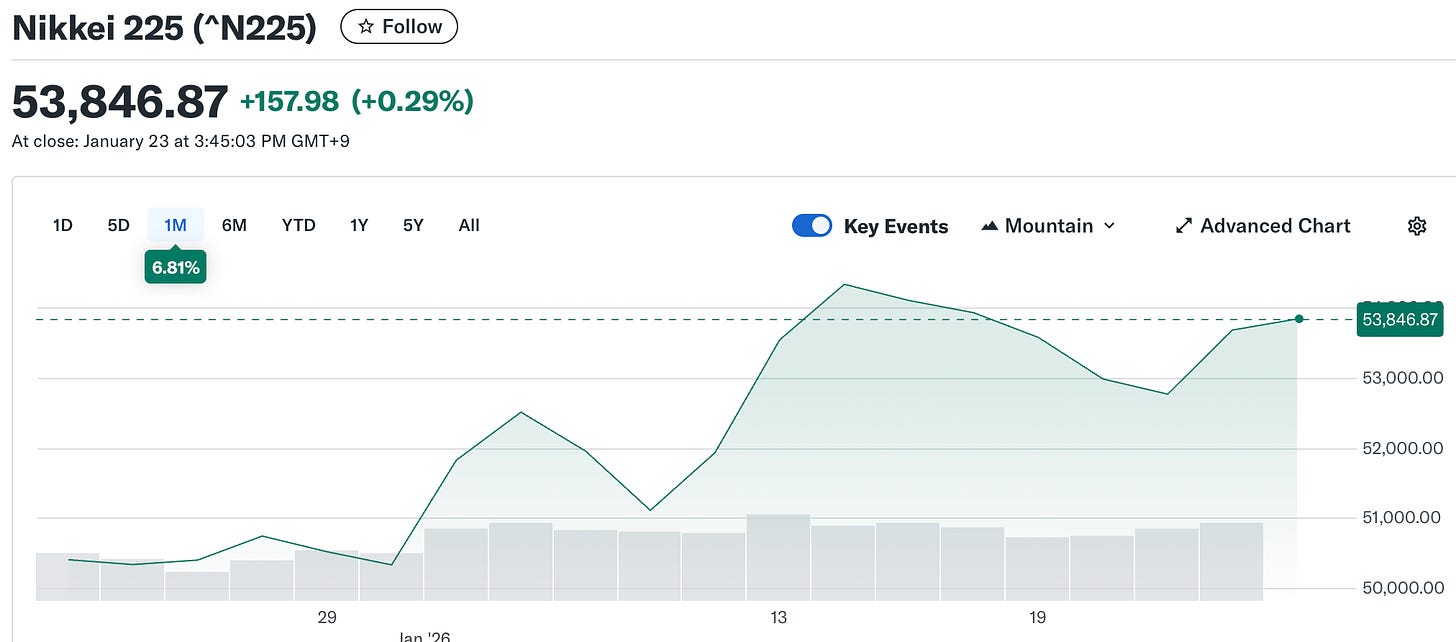

In contrast, Japanese stocks have been moving higher during the past few weeks, even as interest rates moved much higher:

Pundits often focus too much attention on movements in interest rates, without first considering the cause of the change in rates. Long-term bond yields rates can move higher for a variety of reasons, including stronger expected NGDP growth and increased worries about fiscal sustainability. Co-movements in other financial markets—especially stock prices— can provide a useful indicator of the underlying cause of the higher bond yields. Stronger nominal GDP growth will often (not always) lead to higher stock prices, while a fiscal crisis might be expected to reduce stock prices.

After decades of near-zero interest rates, people are naturally surprised to see Japanese rates rising sharply. Yet despite the recent run-up in long-term interest rates, the Japanese 30-year bond yield remains roughly 120 basis points below the levels in the US. Given that Japan shares our 2% inflation target, the actual mystery is why Japanese interest rates remain so low. When two countries with low default risk are both targeting inflation at 2%, you might expect similar long-term nominal bond yields.

In my book The Midas Paradox, I closely examined the relationship between financial asset prices and macroeconomic policy shocks during 1929-38. I found that the reaction of individual markets was often hard to interpret. In those cases, looking at co-movements in a variety of markets helped to clarify why shocks were impacting the economy. For instance, the Smoot-Hawley tariff of 1930 didn’t just sharply depress stock prices, it also led to lower commodity prices—suggesting that the effect was deflationary. This is one reason why I wasn’t surprised that the Trump tariffs have not had much effect on inflation—the positive impact on import prices can be at least partially offset by the negative impact on the broader macroeconomy.

More By This Author:

Which One Doesn't Belong?The Nguyens And The Fed

13 Years Later: The Lessons Of Abenomics