We Have Never Been More Reliant On The Fed

A lot of the small banks in the US are technically insolvent. That sounds scary. And it could be, but only maybe. Because on the other hand, the banks aren’t actually insolvent. Not in real life -- most of them, anyways. But The Street isn’t exactly sure which ones are and which ones are not. That’s why the US banking index (KRE) has such a horrible chart.

Most banks are still going about their business – making loans, taking deposits, etc. In fact, most banks are still making a lot of money, just as their first quarter earnings showed. As long as the banks collect on their loans, as long as there is no devastating recession, and maybe most important: as long as the banks can continue to hold their assets through to maturity and not be forced to sell, they will be just fine.

In other words, everything may work out. Unless it doesn’t.

Banking Make-Believe

How can everything either be just fine or totally off the rails? Talk about black and white. Welcome to the world of banking. It’s a true confidence game. The difference between good and awful comes down to mark-to-market.

You may remember mark-to-market from its top billing in the Great Financial Crisis. Back then it was the mark-to-market of mortgage loans that threatened the system. Today it is, well, actually it is still largely the mark-to-market of mortgage loans. But this time there are also other loans and securities as well.

Mark-to-market means just what it says: pricing the asset at what the market would pay for it today. We do this every day with our own portfolios. We open our bank app and are greeted with the value of portfolio is at that minute. That is mark-to-market.

But banks do not typically mark their assets to market—almost never with their loans and often not with their bonds. Why? Because banks have no intention of selling them. It is the job of a bank to hold a loan until it comes due (with a few exceptions, of course). Most loans and securities on a banks balance sheet are priced at what they were made at, not at what the market would pay for them on any given day.

The Big, Bad Fed

There’s really only one scenario where the mark-to-market value matters to a bank -- if there is a sudden, massive change in interest rates that occurs over a very short period of time. Which almost never happens—except last year, when it did.

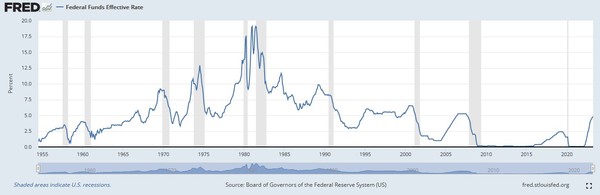

When the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates, it was not the most they have ever done, but it was probably the fastest since the 1970's. And it was the first time they had raised them this fast from 0%, which had an outsized impact on the price of assets.

Source: St. Louis Fed Economic Data

Kicking the Can

The one thing that is on the side of the banks is time. Every month that passes, their loans and bonds get a little closer to coming due. When a loan comes due, it will get paid back at par. The bank that owns it is a little closer to being made whole. The Fed knows this. They are trying their best to kick the can down the road.

The Fed has now created a lending window that lets the banks park their underwater securities at par, while they wait for them to come due. The Fed said that they would take any and all government and quasi-government bonds, stuff like Fannie Mae, Ginnie Mae securities, at par value, so even better.

What that means for the bank is that they can take their $150 TLT equivalent bond, give it to the Fed, and get $200 worth of credit. It is effectively a way of artificially pumping reserves into banks. Instead of holding an underwater bond, they can hold cash – if they need it. When you see/hear people talking about the $160 billion at The Fed Window and how it’s money printing, this is what they are talking about.

Is it really money printing? That might be a stretch. But it certainly is giving the banks a lifeline when they really need one. Without this, I can almost guarantee the Dow/S&P charts would look a lot more like KRE than they do now. Investors are completely reliant on The Fed right now for this.

One could argue that these big board index charts are pricing in almost no systemic risk. And to be fair, big banks are not in (near as much) trouble.

The Schwab Scenario

There are plenty of banks that are at the center of this storm, but the stock that has held my curiosity the most has been Charles Schwab (SCHW). Schwab just seems like such a stalwart. You’d expect Schwab to run into trouble about as much as you’d expect JPMorgan (JPM) to run into trouble. Yet trouble is exactly what it found.

Everybody says Schwab is unfairly sold down because they’re enjoying great account growth, they’re taking share, their earnings are up, etc. Yet the stock price keeps going down.

Source: Stockcharts.com

Schwab may not be as safe as everyone says. If you tweak your numbers enough, make some assumptions about the cut they would have to take on their assets if they absolutely had to sell them tomorrow, you can imagine a distressed scenario where the company’s earnings would be a lot less.

We often think of Schwab as a broker, but Schwab is also a bank. And banks need to maintain capital. Schwab, like all banks, has capital, but some of that capital is underwater if it is marked-to-market.

Now if something went south and Schwab was in the place of having to sell assets, they probably wouldn’t be able to – at least without raising more capital to offset the loss – by selling shares. If Schwab did that, the dilution would lower EPS.

Schwab is really the poster-boy for the entire banking system right now. It is not about whether they are going to make it – Schwab is going to make it – it is more about what the earnings look like on the other side.

Schwab made $6.6 billion last year, or $3.52 EPS. With some not-so-heroic assumptions, you could spitball $5 billion of forward earnings on a higher share count to get less than $2.50 EPS. Suddenly that $50 share price is 20x earnings and the stock isn’t looking “cheap” anymore. What can be said for Schwab can be said for much of the system.

Two Possible Outcomes

In the first scenario, we scoot on through with a version of 'extend-and-ignore.' Eventually the mark-to-market losses get amortized and marked toward maturity. In the second outcome, events happen that cause “a deleveraging event.” That means banks become forced sellers of assets. If this happened and the Fed didn’t step in (though I think they would), they would all be taking massive losses.

That’s why investors are so dependent on the Fed. This whole thing is like watching a child chase a ball into the street as a car barrels ahead further down the block. You don’t know how it ends. You think the driver of the car is probably going to see the kid, it is probably going to stop in time, or someone else could even jump out in the street and save the day. In other words, there are a lot of things that could go right.

But there is one outlier scenario where things could go very, very wrong. The thing about banks is that the whole system can quickly become reflexive, self-reinforcing. That can create a downward spiral. And that is the big risk.

There has been a big spike in downside volatility in the last few days. You know, something that anticipates the possibility of big down days. A lot of this is going to depend on the Fed. More importantly – to take their foot off if it begins to look like that spiral is about to start. I really hope that they manage to get us through this. If they do, this could be the start of the next bull market.

More By This Author:

How GFL Environmental Became A (Renewable) Natural Gas PlayHow Profitable Is Solar – Really?

Take-Out Valuations Say: The Big Money In Energy Is In The Renewable Sector

Disclaimer: Under no circumstances should any material