The Smashing Effects Of A Trade War

Image by Steve Buissinne sourced from pixabay

There was a period of time when I was obsessed with home improvement shows. I’d watch almost anything on the subject: Backyard makeovers, kitchen remodels, gut renovations, you name it. It’s fascinating to see what a skilled craftsman can do with the proper tools. In fact, if there’s one lesson I learned from these shows it’s the importance of using the right tool for the job.

This principle has broad application beyond the scope of carpentry of course. In my opinion, the weaponization of trade by the U.S. and Chinese administrations qualifies as such. There are clearly foreign policy issues between the two countries that require addressing. Economics is simply ill-suited for this job. Like a carpenter making a precise cut, using the wrong tool can lead to disastrous results. Thus, I believe that the escalating trade war and trend towards de-globalization are negative developments for markets. Kindly check your politics at the door for this one.

It’s Political

I must admit, I just recently realized that the U.S. and China are in fact in a trade war. For a long time I took this term’s usage in the media as hyperbole. “The press will print anything to attract eyeballs; hysteria can motivate a political base to action; people don’t mean what they say”; I thought all of these. It was only after watching a series of interviews presenting a specific viewpoint on U.S.-China relations when I fully grasped the gravity of the situation.

I believe that we are in fact at war—or at the very least—in a political conflict. My epiphany came from a 3-part interview series on Real Vision hosted by the outspoken critic of China, Kyle Bass. The first one featured Harvard professor Graham Allison, the author of Destined for War. The potential for a conflict between the U.S. and China were discussed. The rise of latter was posited to threaten the balance of political power that presently exists. This was followed by a jaw-dropping interview with Guo Wengui, a.k.a. Miles Kwok. Mr. Kwok is a wealthy Chinese businessman and outspoken critic of the Communist Party. His accusations of corruption, extortion, and even murder against the party make organized crime look tame. He is living in secretive exile out of fear for his life. The series concluded with an interview with Steve Bannon detailing his opinion of China’s foreign policy.

The theme of the series is quite clear: The rise of China is a threat to global stability; the Chinese Communist Party is an immoral institution bent on increasing its political influence; they will/have resort to whatever means necessary—including stealing intellectual property, extorting their citizenry, lying to western institutions, supporting their own commercial intuitions, and even murder—in order to achieve their goal of world domination. To be sure, these are serious accusations. Real Vision and Mr. Bass did not pull any punches.

This message is quite similar to others heard from the Trump administration. A recent article in The Atlantic discusses the influence that Peter Navarro has had in crafting foreign policy. According to the exposé:

“Such wariness of foreign goods is not just [Mr. Navarro’s] consumer preference—it’s United States policy. In the past year, the Trump administration has embarked on a trade war with sweeping geopolitical aims: The entire government now has a mandate, if a murky one, to make China play by the rules—and also to slow its rise.”

Regardless of your opinion of this viewpoint, it is an important one for investors to understand. They are the dominant ones presently being expressed by the Trump administration. The personnel and policies that manage the Chinese relationship have decidedly turned hostile. China is viewed as a political threat to the U.S. and one that requires immediate addressing—rightly or wrongly so.

For a myriad of reasons, the U.S. is employing economic measures to conduct its foreign policy. Consequently, I believe that the fallout that may result from de-globalization is of secondary concern. If true, this could be dangerous from an investment perspective (and for anyone accustomed to the pleasantries created by globalization). Economics is simply ill-suited for the job of resolving political conflicts. Abandoning existing commercial arrangements and re-localizing can only destroy value. To illustrate we can invoke the works of Adam Smith, Frédéric Bastiat, and Nobel Laureate James Tobin to provide a framework for further analysis.

An “Enlightened” Framework

Adam Smith eloquently illustrated the immense virtues of trade in 1776 in his infamous book The Wealth of Nations. Specialization has underpinned the rising living standards of billions of people throughout history. From the spice traders traversing the old Silk Road to the numerous border crossing taken by automotive componentry, the ability to transact freely with others benefits all parties involved. If not, no trade would occur. “Fair” or unfair, only that it be voluntary matters.

“It is the great multiplication of the productions of all the different arts, in consequence of the division of labour, which occasions, in a well-governed society, that universal opulence which extends itself to the lowest ranks of the people.”

— Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations

But what about the positive impacts of domesticating all of that foreign capital? Wouldn’t this spawn an investment boom at home? In my view the proponents of these opinions underestimate the cost of abandoning capital.

Globalization has increased economic complexities. The result of this drive towards specialization is enhanced efficiency and productivity.Consequently, an immense amount of value is created. We take this interconnectedness for granted, so much so that “grown locally” or “made in the USA” serves as product differentiation. De-globalization would require (in most cases) radically altering the existing capital base. This sounds easy from the ivory tower; significantly harder from the corner office. Good luck relocating facilities, replacing qualified personnel, re-sourcing quality raw material, re-aggregating capable suppliers, realigning freight capacity, re-striking financial arrangements, etc. without severe disruption. Said simply, there is a vast amount of capital—financial and human—presently invested and functioning at a high capacity.

Another Enlightenment thinker can illustrate. Mr. Bastiat’s parable of The Broken Window in That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen (1850)—perhaps my favorite economic essay of all—does so quite eloquently. Recanting a fictional tale of a shopkeeper, James B., Mr. Bastiat debunks the notion that “stimulating” demand by force can be a boon to economic growth. Economists get this so frequently wrong because “that which is not seen” is never considered. Opportunity costs are conveniently ignored.

In The Broken Window, a window in James B.’s shop breaks. To some this is viewed as a positive development as it will spur economic activity. The window must be replaced after all which employs the services of the glaziers. The economic flywheel has been set in motion, it is thought. Mr. Bastiat is quick to object:

“But if, on the other hand, you come to the conclusion, as is too often the case, that it is a good thing to break windows, that it causes money to circulate, and that the encouragement of industry in general will be the result of it, you will oblige me to call out, ‘Stop there! your theory is confined to that which is seen; it takes no account of that which is not seen.’”

Destruction cannot lead to prosperity. This only becomes evident when “that which is not seen” is considered. In the case of James B.’s window:

“Now let us consider James B. himself. In the former supposition, that of the window being broken, he spends six francs, and has neither more nor less than he had before, the enjoyment of a window.

[If] we suppose the window not to have been broken, he would have spent six francs on shoes, and would have had at the same time the enjoyment of a pair of shoes and of a window.”

‘Society loses the value of things which are uselessly destroyed;’ and we must assent to a maxim which will make the hair of protectionists stand on end — To break, to spoil, to waste, is not to encourage national labour; or, more briefly, ‘destruction is not profit.’” [Emphasis is mine.]

These are seemingly simple yet deeply profound words. To destroy in the name of creation is oxymoronic. The ability/capacity to produce is always there. You can have a window and shoes which is preferable to just a window; one simply needs to look beyond the glaziers.

To champion the destruction of existing supply chains and business models is akin to breaking windows in the name of economic revitalization. It is a consideration for only the seen and ignores the less obvious and better possibilities for what already exists. Like James B., we—as a whole—will be poorer as a result of de-globalization.

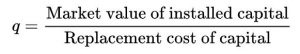

Dr. Tobin can also help frame this issue for us. He is best known for his “Q ratio”, or “Tobin’s Q.” Tobin’s Q is a fundamental investing valuation metric. While not popularly used in day-to-day trading activities (to my knowledge), it does have niche utility.

Tobin’s Q is a ratio calculated by dividing the total market value of a firm by the replacement value of the firm’s assets. The former is derived from the market price of its securities. The latter must be estimated by analysis. The theory goes that if the market value is less than what it would cost to recreate the company anew, the company is undervalued. Its traded securities should probably be bought. If the ratio is greater than 1, investors might be ascribing too much value to the firm.

Tobin’s Q. Source: Wikipedia

The imposition of tariffs and other policies aimed at altering the existing, global supply chain essentially impairs the value of companies. The profitability profiles of oversea factories and supply agreements decline by sheer decree. Even worse is the abandonment of perfectly good capital for sake of relocating them to more favorably treated jurisdictions. This equates to lower enterprise values. In Tobin’s Q terms, existing companies potentially become overvalued. Not only should some value of perfectly good assets be written off (lowering the numerator), the replacement value becomes more attractive (increasing the denominator).

An Illustration Of Political Means

As stated, I believe that the escalating hostilities between the U.S. and China should be addressed using political means. What exactly do I mean by this? While I am no expert in foreign policy, the following example could prove illustrative.

The theft of U.S. intellectual property (IP) by Chinese agents is one issue that the imposition of tariffs is meant to address. As a staunch defender of individual rights, I believe that the U.S. government has a role to play here. However, tariffs do nothing to protect the property rights of victimized individuals and companies. Rather than punish the guilty, tariffs indiscriminately penalize everyone engaged in global trade. In fact, absolutely nothing is done to prevent the perpetrators from continuing. The thieves are left free to operate. Tariffs pose no serious deterrent.

A proper policy, in my view, is to ban the importation of any goods containing stolen IP. This would directly punish those—and only those—who have stolen. Much like the U.S. government properly bans the sale of knock-off pocketbooks and sneakers, the same should be done with industrial and technology goods and services. The innocent should be left free to trade with whomever they desire. The government should also pursue diplomatic dialogue and seek local enforcement to shut down these illegal operations.

The Right Tool Is Needed

The historical record of the benefits of trade speaks for itself. Only a politician or academic could be so indifferent to the evidence. Thus, whether a trade war is “winnable” or not is irrelevant, in my view; what is is whether trade and other economic policies will be called upon to do the bidding better suited for political means. Should the U.S. and Chinese administrations continue down this path, the results are likely to be as disastrous as using a hammer to do the work of a saw. The clean and elegant cut envisioned by policy architects is more likely to result in the smashing, mangling, and fragmenting of economies and markets.

The right tools are needed if one hopes to achieve craftsman-like results. Let’s hope our policymakers reach for the correct ones when conducting foreign policy and leave the economy out of the dispute. Allowing markets to freely function is the best way to mitigate any destruction that might occur as a result of a political conflict.

Good stuff.

Thank you!