The Next Economic Downturn Will Be Here Soon Enough

One of Ludwig von Mises’s brilliant achievements was his elucidation of Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT) in his great 1912 work The Theory of Money and Credit. Mises expanded upon preexisting Austrian capital theory, which stresses the importance of time and uncertainty associated with the transformation of inputs like labor and natural resources into the final goods desired by consumers. The value-maximizing allocation of inputs over different lines of production (each having its own time horizon and degree of uncertainty) is regulated by the time and risk preferences of savers; the market prices of which are expressed in the form of money interest rates.

The central insight of ABCT is that when fractional reserve banks create money and credit deposits out of thin air to expand extensions of credit to private sector businesses, they upset this allocation of inputs, driving the structure of production out of balance. Ordinarily, investment spending is associated with corresponding acts of thrift, where a saver’s restraint of spending on present consumption not only provides funding for greater investment spending, but also liberates labor and natural resource inputs from less interest-sensitive sectors of the economy (i.e., those requiring less time and less risk tolerance) towards the more interest-sensitive sectors. Thrift is what makes a shift of inputs towards more time-consuming and less certain lines of production (i.e., towards the lines of production favored by lower interest rates) sustainable.

The fundamental problem with fractional reserve bank credit is that it funds greater investment spending without the corresponding thrift. Bank credit expansions drive down interest rates artificially, causing too many labor and natural resources inputs to be diverted towards the more interest-sensitive parts of the economy with too few invested in the less interest-sensitive sectors—these inputs are malinvested in unsustainable boom sectors.

Such booms can’t be sustained because demand for inputs in the short-term, lower-risk sectors isn’t slackened sufficiently by thrift to match the higher bank credit-fueled demand for inputs from the boom sectors. Input prices increase relative to output prices, eventually squeezing business operating margins to the point where losses begin to appear, particularly in the boom sectors. Once that happens, a boom then must turn into a bust, often accompanied by mass loan defaults that threaten the solvency of fractional reserve banks.

When using ABCT to make sense of real-world situations, it is important to keep in mind that malinvestments are often sector-specific. The artificial reduction of interest rates doesn’t uniformly affect every sector, as investments in some sectors are more heavily discounted than others due to longer time and/or greater uncertainty associated with their returns. Since the relevant time horizons and perceived risks of each line of production are constantly changing, no future cycle is ever going to be exactly like a previous cycle.

Moreover, attempts by investors to learn from past cycles in order to avoid cyclical risks tends to be foiled by such dynamic changes in sector specificity. Booms are often concentrated in sectors that, in addition to being interest-sensitive, are also incorrectly perceived by most investors as being less prone to cyclical risks than they actually are; investors being misled by experiences of past cycles or by a complete lack of prior experience with a new sector, as is frequently the case with investments involving emerging, highly promising technologies. The dotcom bubble of 2000 is a notable recent example of such an emerging technology-focused boom.

Furthermore, commercial banks don’t behave like normal profit-maximizing lenders, having little of their own capital tied up in their loans and no personal shareholder responsibility to make good on depositor losses. Bank shareholders can profit from taking excessive risks while having the costs socialized, usually in the form of deposit insurance and bailouts. Attempts to regulate this moral hazard mean that bank regulations often control which interest-sensitive sectors receive the most bank credit and thus become the most vulnerable to a bust. For example, the peculiar focus of the financial crisis of 2008 on residential subprime mortgages was a consequence of the Basel II bank capital regulations being implemented by large banks at the time. Basel II regulations incentivized banks to lend to Special Purpose Entities (SPEs) created by investment banks that pooled such dodgy mortgages, conjuring the illusion of senior debt securities safe enough for bank portfolios by adding equity, junior debt, and “credit insurance” to SPEs as alleged loss buffers (the sort of delusional financing highlighted in the 2015 movie The Big Short).

So what can an ABCT-informed analysis tell us about our current situation? Where will the next downturn strike?

At present, there is evidence of both a tech-oriented bubble driven by infusions of credit and of large-scale bank credit problems. While ABCT doesn’t enable us to predict the timing or the intensity of the next bust, understanding the role of bank credit as the key causal factor does help us spot where likely malinvestments exist.

On the tech bubble side, one fairly obvious area of concern is the tremendous surge in artificial intelligence investments, much of it concentrated in just seven prominent high market-capitalization/rapidly-growing companies (the “Magnificent 7”). The financial press has already noted how the AI bubble is being boosted by a massive influx of credit (the cumulative total now on the order of hundreds of billions of dollars). Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai has compared AI investing to the dotcom boom of the late 1990s, warning that even his own company, along with many others that have engaged in excess AI investing, won’t be immune to a bursting bubble.

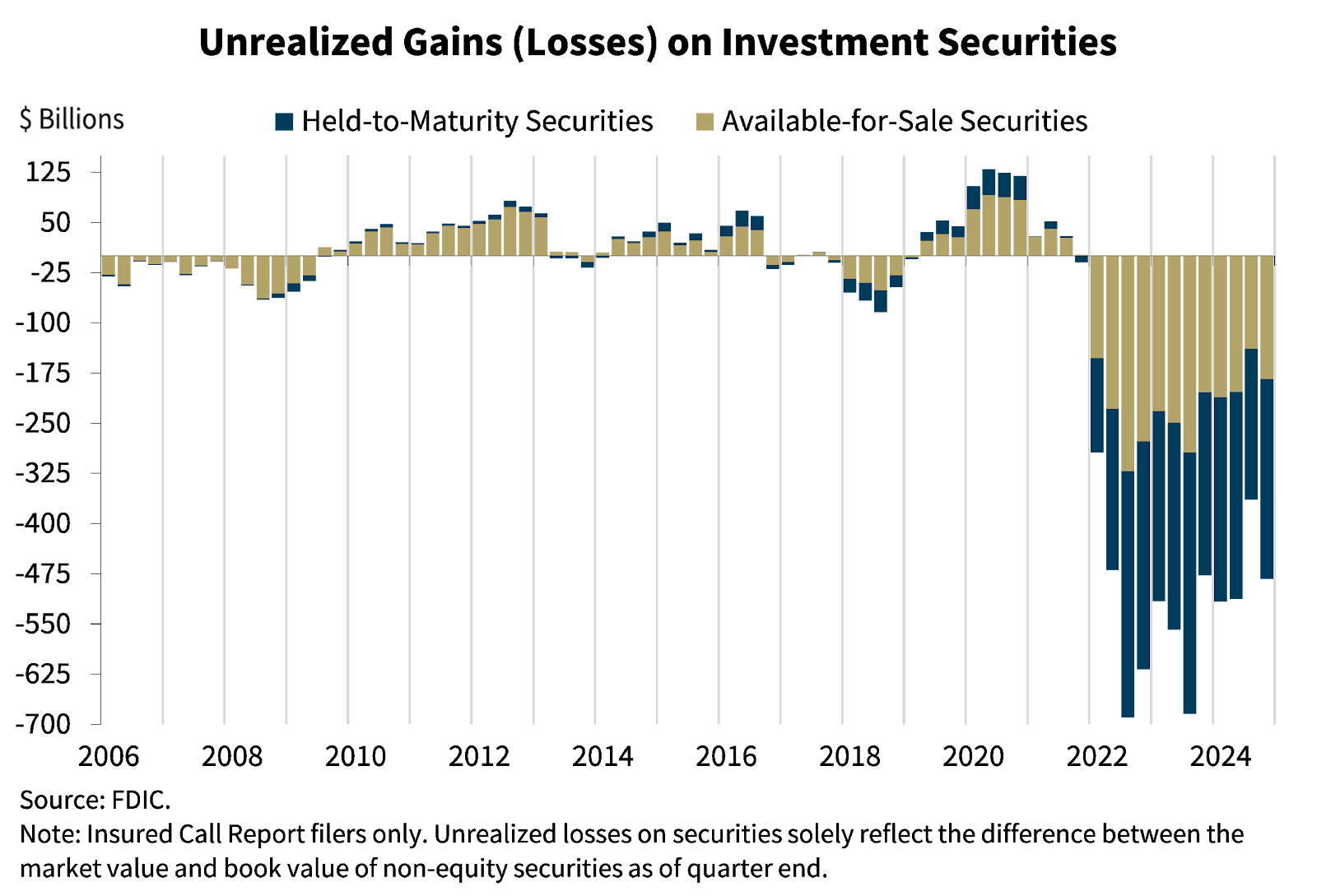

On the banking side, there are two troubling developments that haven’t received nearly as much attention as the AI bubble, but clearly point to additional sectors where credit-fueled malinvestments are rampant. One area of concern is the huge overhang of bad debts left over from the era of covid lockdowns, mainly in categories like commercial real estate where market values became considerably less than the original book values that years later are still being accepted by bank regulators and accountants on the asset side of bank balance sheets. Figure 1 quantifies the extent of this problem for debt securities that have market prices (currently showing mark-to-market losses of approximately half a trillion dollars); there are undoubtedly further substantial losses associated with bank loans that are not classified as investment securities and thus lack market prices.

Figure 1: Unrealized Losses in Bank Investment Securities

Source: FDIC

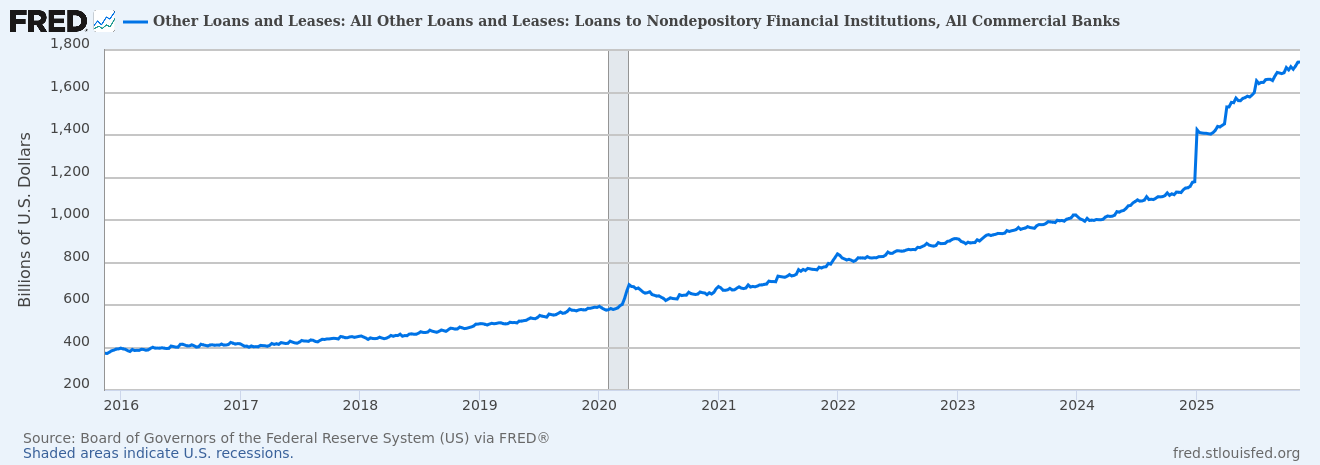

Another area of concern is the rapid growth of a relatively new category of lending, namely, bank loans to “nondepository financial institutions” (NDFIs). Recent NDFI defaults affecting two large regional banks—Zions Bancorporation and Western Alliance Bank—have alarmed domestic and foreign observers who track the NDFI sector; these incidents demonstrate that NDFI defaults can lead to frighteningly rapid, near-total losses for their bank creditors. Basel III bank capital regulations and the Dodd-Frank Act have incentivized bank lending to NDFIs today in much the same way that Basel II regulations encouraged subprime mortgages via bank lending to SPEs during the boom leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, and seems to have spawned an unintended opaqueness of actual default risks and massive fraud in much the same way that the Basel II/subprime mortgage fiasco did.

The NDFI sector consists of a wide variety of non-bank lenders like subprime auto lenders, mortgage originators, payday lenders, equipment financing companies, commercial real estate bridge lenders, fintech lending platforms, and private credit firms. In essence, NDFIs can make the sorts of risky high interest loans that banks themselves aren’t allowed to make, but NDFIs themselves are considered creditworthy enough under current regulations for banks to lend to. Bank lending to NDFIs thus serves as the latest form of regulatory arbitrage, bypassing bureaucratic attempts to prevent bank exposures to the steadily deteriorating credit quality that always afflicts unconstrained bank credit expansions. Regulators never seem to learn that no mandated equity buffer is ever enough to avoid necessitating massive bailouts or timely central bank-engineered credit crunches.

Commercial bank lending to NDFIs (figure 2) has been the fastest-growing lending category lately, multiplying nearly five fold over the past ten years and growing an astonishing 47 percent over just the past 11 months. NDFI loans now exceed $1.7 trillion, accounting for nearly 10 percent of all bank credit. Moreover, NDFI lending is concentrated mostly among larger banks, once again raising a specter of “too big to fail” bailouts.

Figure 2: Bank Lending to NDFIs

Source: FRED®

When asked about the risk of a recession, Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessant confessed that housing has been “struggling” and even that interest-sensitive sectors are already in recession, but quickly pivoted to expressing a completely unfounded confidence that the administration’s “One Bloated Brobdinagian Bill” would cause “noninflationary growth” in 2026. However, the evidence of unliquidated malinvestments on the order of hundreds of billions of dollars implies that the “struggling” can only intensify and spread to more sectors of the economy, while thrift-deterring, capital-consuming fiscal policies like the “One Bill” will cripple any recovery.

More By This Author:

Money Remains A Medium Of Exchange And Is Not A Series Of Data PointsThe Government Is Lying About Inflation

The K-Shaped Economy

Mises Institute is a tax-exempt 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Contributions are tax-deductible to the full extent the law allows. Tax ID# 52-1263436.

Note: The views expressed on Mises.org ...

more