Rethinking Recessions

Recently, there’s been a tendency for people to try to expand the definition of recessions. You see people talking about declines per capita GDP in Australia, or “manufacturing recessions” in various countries.

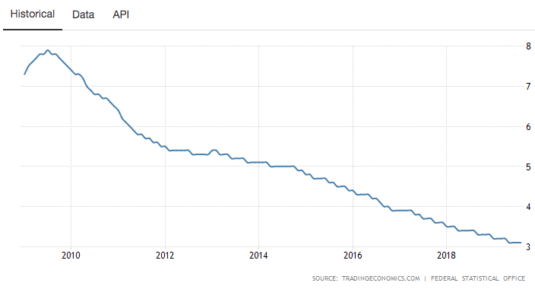

I’d like to see us go in the other direction, tightening the definition. In the past, I’ve discussed three “phony recessions” in Japan during the past nine years. In each case, there was a brief period of negative RGDP growth, and then a rebound, with no increase in the unemployment rate. Because Japan has a rapidly falling population, its trend rate of RGDP growth is quite low. It doesn’t take much to drive them into a brief mild recession. But it’s not really much of a “business cycle”.Here’s the Japanese unemployment rate:

(Click on image to enlarge)

The smaller the economy, the more erratic is the rate of growth in RGDP, as individual sectors can have a bigger impact on the total. Germany’s important manufacturing sector is currently in a slump, and it threatens to push Germany into a technical recession:

Germany’s central bank warned the country’s economy may have shrunk for its second consecutive three-month period, which would mean the eurozone’s biggest economy has entered its first recession in six years.

But does this actually matter?

The labour market has cooled in Germany recently, but unemployment continues to fall, the Bundesbank said. In September the number of people registered as unemployed fell by 10,000 from the previous month to 2.28m, its first fall in four months.

Does this look like a country in recession?

(Click on image to enlarge)

Keep in mind that manufacturing is a relatively small share of the economy in most developed countries, and a slump in capital-intensive manufacturing can affect output more than

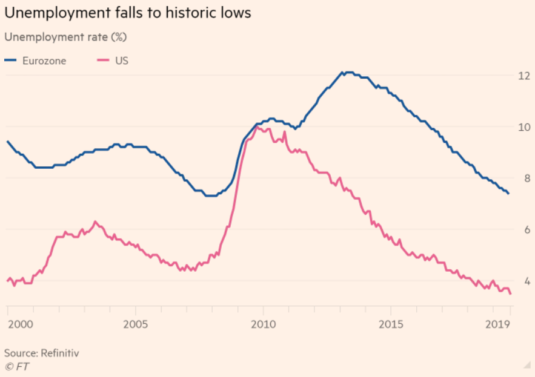

If storm clouds are gathering over trade, investment and manufacturing, they are not, however, seriously affecting households. Unemployment is at long-term lows in many advanced economies and with real incomes rising, consumer spending is preventing recessionary forces taking over.

The US unemployment rate fell to its lowest level in 50 years at 3.5 per cent in September; UK levels are at 45-year lows; and the eurozone rate of 7.4 per cent in August was the lowest for 11 years and within a whisker of the lowest rate since the single-currency area was created.

The recent problems at Boeing are a perfect example of the disconnect between output and employment. The pause in the construction of 737s does have a discernible impact on US output but does not have a noticeable impact on US employment.

(Click on image to enlarge)

BTW, this graph illustrates a point that I frequently make. Even if the central bank undershoots its inflation target for an extended period of time, the unemployment rate will eventually fall back to the natural rate. The ECB needs a much more expansionary policy, but primarily so that it can hit its inflation target. The unemployment rate is already close to the natural rate (albeit still a bit above, as the European natural rate is trending downward.)

My suggestion is that we start defining the term ‘recession’ as a substantial rise in the unemployment rate. For the US economy, a jump of one percentage point might work. Using that criterion, all the recessions and non-recessions since WWII would be exactly the same. In the US, there are no “debatable recessions”.It’s always 100% clear as to whether we are in a recession or not. (The lack of mini-recessions in the US is perhaps the most important unsolved mystery in macroeconomics.)

Going forward, however, the unemployment criterion might yield different results from the 2 quarters of falling RGDP criterion, or the more complex formula used by the NBER in the official recession dating decisions. We already see mini-recessions in other countries. (BTW, contrary to popular opinion, the NBER does not use 2 quarters of falling GDP.)Let’s get ahead of the problem, and not change the definition only after an ambiguous situation shows up. Do it now.

Prediction: The world will see an increasing number of “phony recessions” in the 21st century—recessions with falling output but strong labor markets. The Phillips Curve is now defunct; Okun’s Law is next.

PS. I have a new piece at The Hill that actually praises the Fed for improving its monetary policy, and I suggest that this is why the current expansion is the longest in US history. Of course with my luck, you should now expect a recession within 12 months!🙂

Seriously, I do say in the Hill piece that money continues to be too tight, and that recession risks remain elevated.I see a roughly 30% risk of recession, which is too high.

So, at some point when will rate cuts dig into the zero lower bound? We pay massively for insurance and make no money on savings precisely because the Fed does not take down this economy, and the reason is derivatives!