On Thin Ice

Image source: Pixabay

There is very little wiggle room left in many household budgets, and any decline in income will crack the ice.

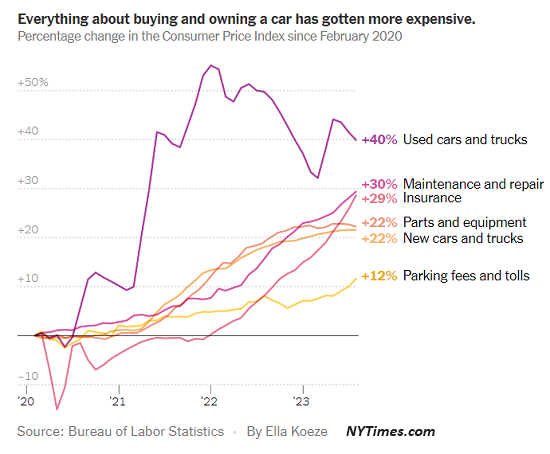

A recent article on a well-worn topic--the rising costs of vehicle ownership--caught my attention. How the Costs of Car Ownership Add Up (New York Times). There's nothing particularly new revealed in the piece, or particularly surprising for anyone who has 1) shopped for a new vehicle 2) shopped for a used vehicle 3) had their vehicle repaired or serviced recently 4) fueled up at a gas station, or 5) paid auto insurance.

The most striking point was not explicitly said: these astounding increases in costs are putting many American households on very thin ice financially. There are plenty of statistics saying the same thing: a large percentage of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck and have less than $1,000 in a rainy-day / emergency fund, wage increases are lagging behind the soaring cost of living, and so on.

But statistics tend to be abstractions. Specific line-item increases on goods and services we all buy bring it home with a Are you kidding me? 2X4 upside the head.

I have no idea if the five households surveyed are typical, but the costs of vehicle ownership in each case closely match the AAA average annual cost of about $12,000 per vehicle.

I was also struck by the role dumb luck played in households' vehicular fortunes. Those who happened to buy a new or used vehicle in the years leading up to 2020 are now hugging themselves in delight, especially if they were prescient enough to buy a modest-priced vehicle with high resale value due to the durability of the models--for example, a Toyota Corolla or Honda Civic.

Those who were forced by circumstance to buy vehicles post-2020 have suffered spectacularly prohibitive price increases in both used and new vehicles.

A Corolla or Civic bought new in 2017 or 2018 with some modest haggling ("let me check with my manager," etc.) that has been well-maintained with moderate mileage is still worth close to its purchase price five or six years later. Vehicles with high resale values bought used pre-2020 have also seen remarkable increases in valuation, as those who cannot afford a new vehicle are forced to bid on a limited number of more affordable used cars/trucks.

As for repairs and service expenses--they're inspiring many are you kidding me? moments. Anecdotally, I'm hearing about air-conditioning repairs at dealerships costing $3-4,000, basic service charges around $300, and so on. For many, these are "no freaking way" prices.

Way back in 2017 / 2018, dealer financing at 1.9% or even lower was common for buyers with decent credit. One of the vehicle owners surveyed in the NYT article is paying 15% on his used car loan, almost ten times the rate available five years ago. That increase will punch a hole in just about any budget.

I also notice none of those surveyed performed any of their own maintenance. I have never been a high earner, and have generally scraped by on the margins of the economy, so extreme frugality has been my core strategy. We still change the oil in our cars, as modest a savings as this might be, and have done repairs when they were within our skillset: go to an auto parts store, borrow or rent the plug-in device to read the codes of your vehicle's controller board, discover it's a sensor you can replace for a few bucks, etc.

But the 2X4-upside-the-head reality is there's not much anyone can do about skyrocketing ownership costs. The Florida household's vehicle insurance costs were so high I checked with a Florida correspondent to see if these rates were typical. Yes, auto insurance costs in Florida are ridiculously high.

At $12,000 a year per car, that's $24,000 a year for two cars. That means the household has to earn at least $30,000 just to own two cars. With new vehicle loan payments exceeding $700 a month--over $8,000 a year--the obvious conclusion is a new vehicle is now really only affordable to the top 20% of households, earning $130,000 or more annually.

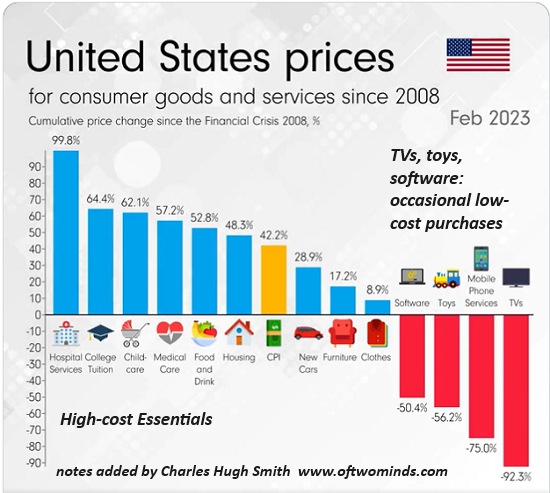

The financial ice is getting thin because these aren't the only big-ticket increases in essentials households have been dealt with. As I noted on this chart of inflation since 2008, the big increases are all in big-ticket essentials such as healthcare, college tuition, childcare, and shelter, while the declining prices are in lower-cost occasional purchases of TVs, toys, and software--purchases that make up trivial percentages of household annual budgets.

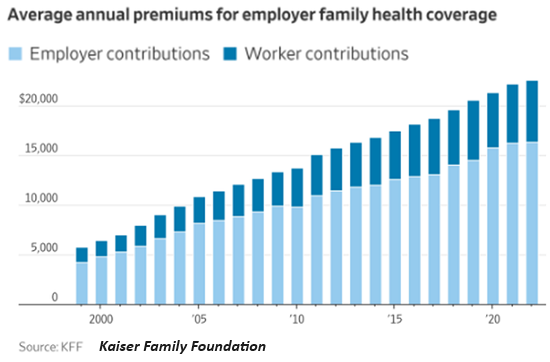

Consider the ever-heavier burdens of healthcare insurance, which is especially burdensome for the self-employed, who have no employer to share the costs:

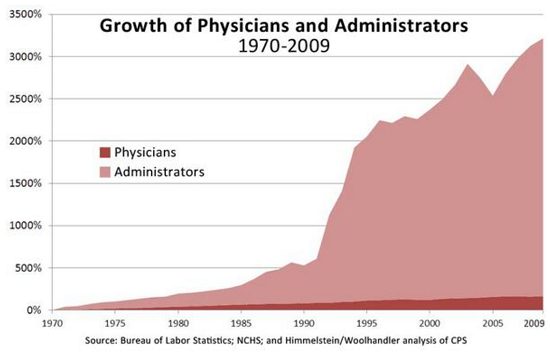

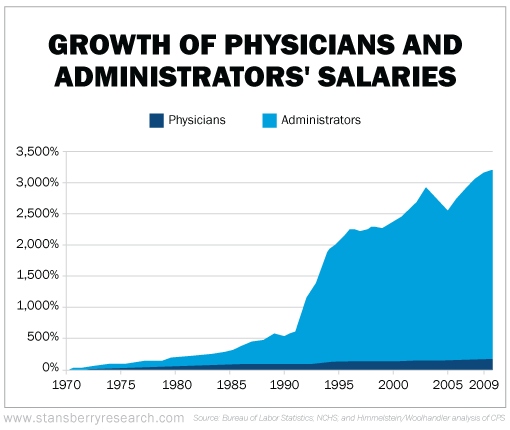

The rise of paper-pushing, regulatory-compliance administrative costs has pushed up zero-value increases in prices throughout the economy. As frontline healthcare workers burn out from overwork, the healthcare sector loads up on more administrators:

Who are paid handsomely:

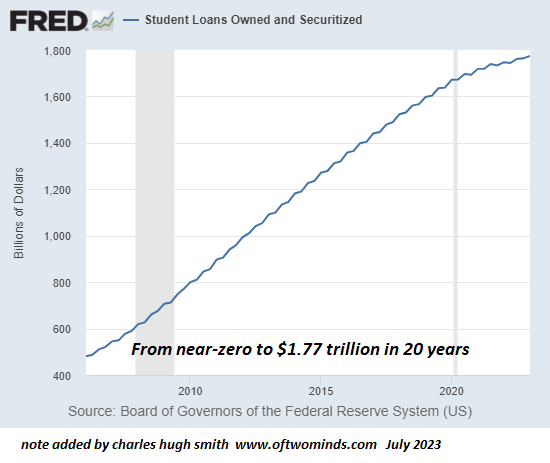

How did American higher education survive before student loans were available to pay all those administrators? It certainly is a mystery how universities functioned without students borrowing $1.77 trillion:

Then there are the policy-driven concentrations of wealth and income in the top 10%, who have seen their share of the nation's wealth and income soar while the bottom 80% lost ground:

I fear the ice is now too thin to withstand the slightest increase in financial pressure. There is very little wiggle room left in many household budgets, and any decline in income will crack the ice.

The only way to significantly reduce expenses is to move to states with lower big-ticket costs such as shelter, insurance, and property taxes, and get as lean and healthy as possible to limit one's exposure to healthcare expenses. But moving to a new state is asking a lot of households, and few will consider it short of a major crack in the ice.

In terms of advancing one's Self-Reliance, it's wise to take control of as much as we can in our lives and move to thicker ice as prudently and promptly as we can.

More By This Author:

How Great Is Our Economy If The Bottom 50%'s Share Of The Nation's Wealth Has Plummeted Since 2009?

Six Reasons Why Corporate Profits Will Fall 50%

The Peculiar Power Of Denial

Disclosures: None.