Measuring Monetary Policy Shocks

What are the effects on the economy when the Fed raises interest rates? This is a key question in empirical research, but is notoriously hard to answer. The reason is that when the Fed raises interest rates, it usually does so in anticipation of a stronger economy or rising inflation. If we look at what happens to inflation or output following an interest rate hike, it is impossible to distinguish the effect of the Fed’s actions from the effects of the changing fundamentals that led the Fed to act in the first place. New research by a graduate student at UCSD may have finally solved this problem.

A common approach that recent researchers have taken has been to focus on what happens to interest rates within a narrow window of time, say 30 minutes to one day, around a monetary policy announcement. If the time window is narrow enough, one can make a strong case that the changes in interest rates within that window were caused by the Fed announcement itself and not by some other news hitting the market at the same time. By looking for the effects of those specific, narrow changes in interest rates on the economy, researchers hope to learn about the effects of the Fed’s actions.

However, as noted by Campbell et al. (2012), Nakamura and Steinsson (2018), Cieslak and Schrimpf (2018), and some of my own work as well, this doesn’t really solve the problem if the Fed has some information about economic fundamentals that the market doesn’t. Any news that inflation or output are headed up, whether the news comes from the Fed or any other source, will be a development that raises interest rates. An announcement by the Fed that it is raising interest rates relative to what the market anticipated may cause market participants to conclude that the economy is stronger than they thought, and this could be the primary reason why interest rates respond to the Fed’s announcement.

Campbell et al. (2012) and Nakamura and Steinsson (2018) documented an interesting observation that supports that interpretation. Suppose we take the change in the 3-month-ahead fed funds futures contract on the day of an FOMC announcement, and regress the change in the Blue Chip forecast of inflation that month on that one day’s change in the futures price. The coefficient turns out to be positive– when the Fed surprises the market by raising rates, private analysts revise their forecasts to conclude that inflation is headed higher. That doesn’t mean that when the Fed raises rates, it actually causes inflation to go up (rather than the Fed’s intended effect of bringing inflation down). Instead it suggests that the change in futures prices on that day is mostly reflecting changes in economic fundamentals rather than economic policy. If the Fed signals it is more worried about inflation, private analysts conclude that maybe they should be more worried about inflation as well. Similarly, one finds an unexpected increase in fed funds futures on the day of an FOMC announcement is associated with a decrease in Blue Chip unemployment forecasts. Again, that’s exactly the opposite of the effect expected from a monetary contraction, and is instead exactly the effect predicted if the main thing the Fed is doing is revealing information about economic fundamentals.

Cieslak and Schrimpf (2018) document another interesting fact. A monetary contraction is supposed to raise rates and lower output, both of which should make stock prices lower. But as often as not, one sees stock prices rise on days when the Fed announces higher rates.

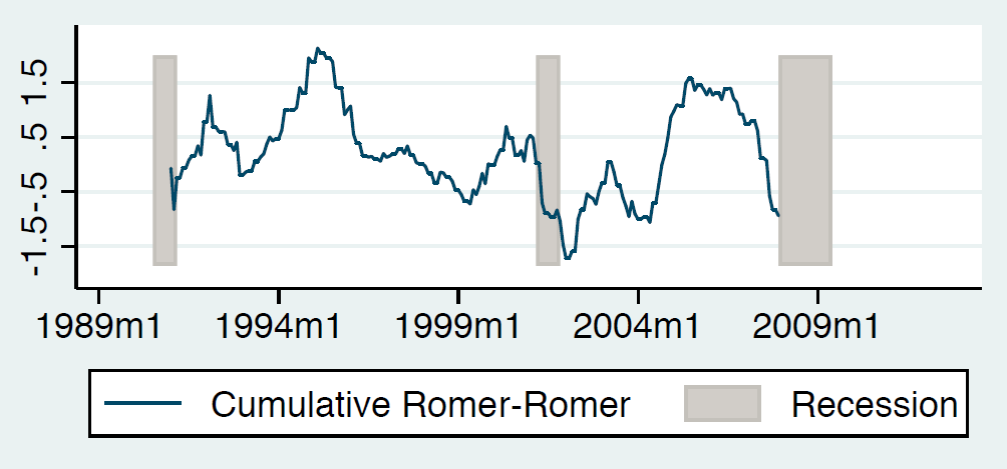

A third way to see the issue visually is to look at the cumulative change in fed funds futures over a 12-month period using just the days of FOMC announcements, as shown in the figure below. The Fed was consistently surprising the market with lower interest rates during the recession of 2001. But clearly with hindsight, the Fed was doing this because it saw the economy as weaker than many private analysts recognized at the time. If you look at the correlation between this supposed monetary shock and economic variables of interest over this period, you’re going to find the effect of the recession, not the effect of actions by the Fed.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Source: Zhang (2018).

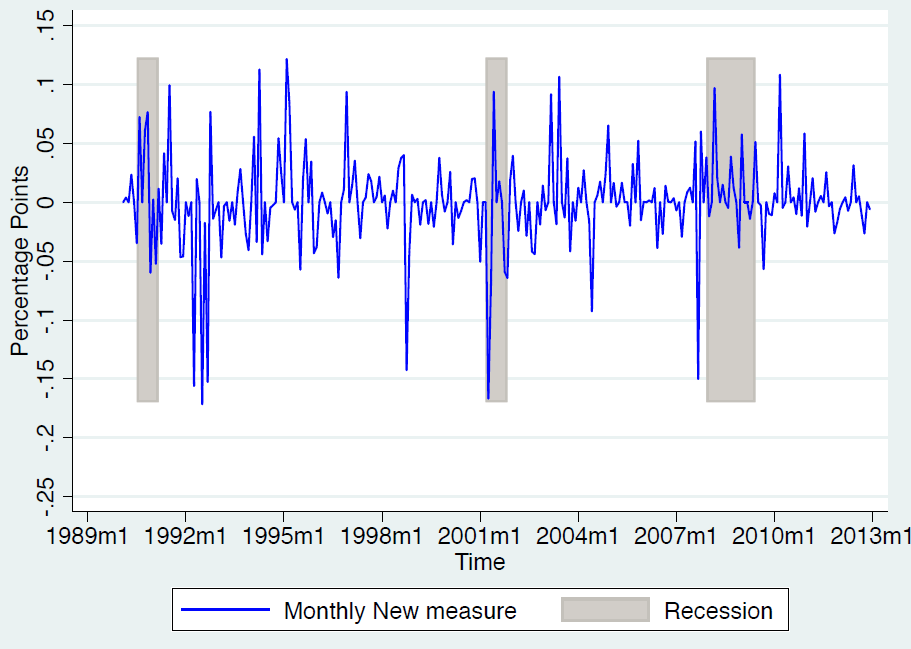

A number of alternative measures of monetary policy shocks have been proposed by other researchers. One of the more promising ideas was developed by Romer and Romer (2004). They proposed to measure the information about economic fundamentals that the Fed had but the market did not by using the Greenbook forecasts prepared by Fed staff prior to each FOMC meeting. Romer and Romer then used the component of changes in the Fed’s interest rate target that could not be predicted on the basis of Greenbook forecasts. A new paper by UCSD graduate student Xu Zhang looks at this and a number of other proposed measures of monetary shocks. Zhang finds, as other researchers have as well, that while the Romer and Romer measure offers improvements over some of the others, it is still the case that their measure has a positive correlation with revisions in Blue Chip inflation forecasts. And, like the other measures, it still shows a definite trend down during the 2001 recession.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Source: Zhang (2018).

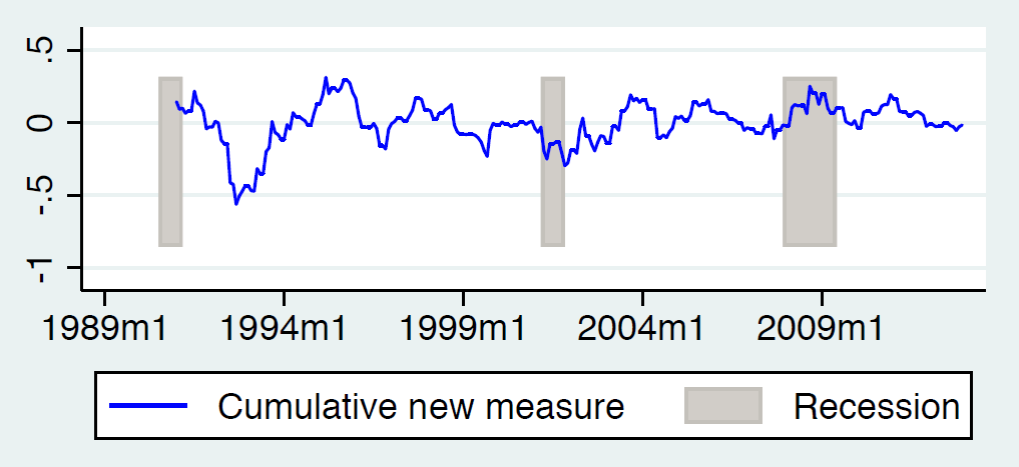

Zhang’s suggested solution begins with the observation by Gurkaynak, Sack and Swanson (2005) that the news revealed by a typical FOMC announcement is multidimensional. The Fed is typically both changing the current interest rate and signaling the changes that are in store for the future. Zhang’s starting point was therefore to look at changes in futures contracts of 5 different maturities– the current and 3-month-ahead fed funds as well as Eurodollars at 2, 3, and 4 quarters ahead– on days of FOMC announcements. For each contract, she regressed that change on the Greenbook forecasts as in Romer and Romer, with the residuals interpreted as the part of that change in rates that could not be attributed to superior Fed information. She then takes the principal component of those 5 residuals as her measure of the shock to monetary policy. The resulting series and twelve-month accumulations are plotted below.

(Click on image to enlarge)

Source: Zhang (2018).

Source: Zhang (2018).

Initial analysis of this measure looks promising. Unlike any other measure that Zhang examined, her measure has a consistently positive correlation with changes in Blue Chip unemployment forecasts at and a negative correlation with changes in Blue Chip inflation forecasts at every horizon. Rate hikes attributed to monetary policy are associated with falling stock prices while rate cuts are associated with rising stock prices more strongly than for any other measure. And unlike all the other measures, her series does not seem to be just another proxy for the state of the business cycle.

I’ll be interested to see what other researchers find with this measure. But my preliminary conclusion is that, if I wanted an empirical measure of true shocks to monetary policy, this is the one I would use.

Disclosure: None.

Fascinating conclusion. Rate hikes kill stocks. Powell paused and stocks got killed anyway, probably from hikes already in place. Coddling the stock bubble is a worse option than helicopter money to the masses, but nobody has accused the Fed of rational thinking. The stock bubble must, somehow, be a reflection of banking strength.