How Much Of A Risk Is The Coming Debt Limit?

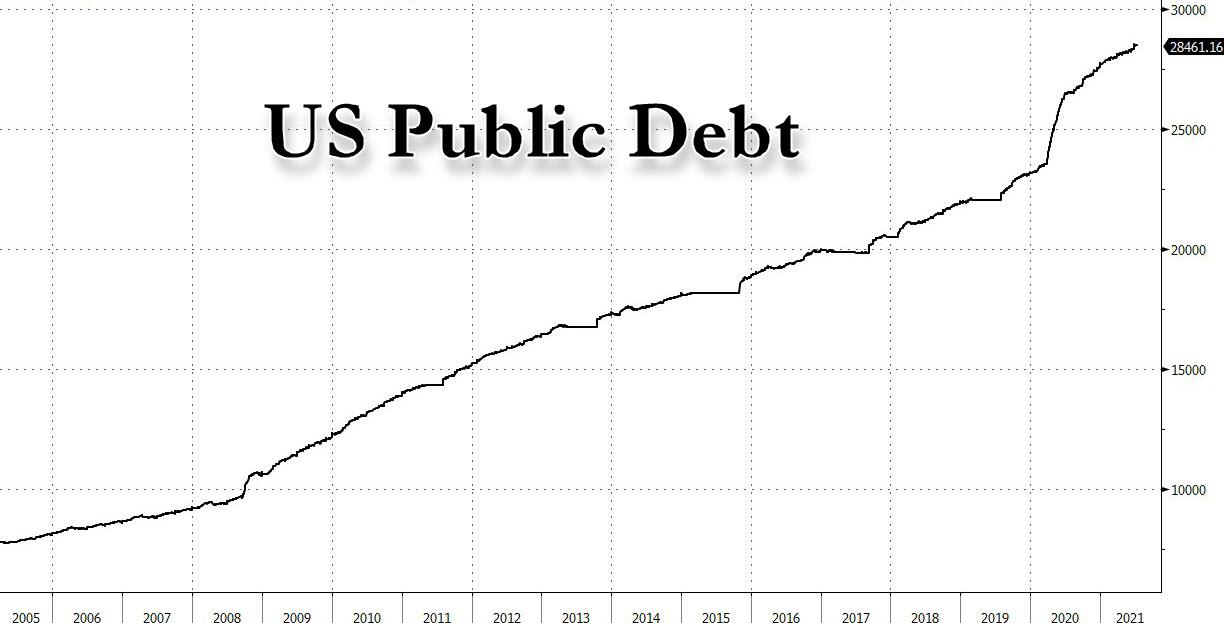

With Bloomberg headlines hitting and reminding us that it's time for the periodic debt ceiling drama, as Janet Yellen said in a letter to Congress leadership that the Treasury will start special measures due to debt limit, and warning that the now familiar special steps could run out soon after Congress recess ends, it's time to remind readers what all the drama is (or rather will be) about, while also reminding that total US debt will hit $30 trillion in about six months.

(Click on image to enlarge)

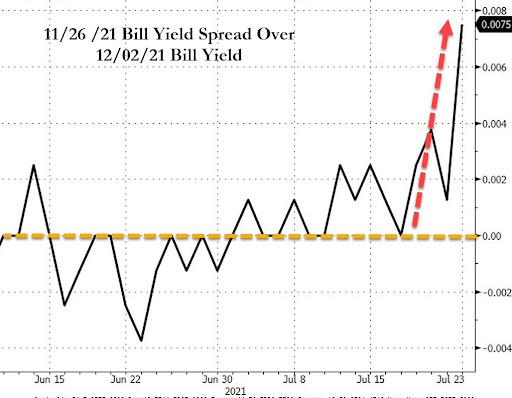

With the now mandatory late November "kink" starting to emerge in T-Bills as some in the market try to arb out the risk - modest as it may be - of a technical US default...

... Goldman's chief political economist Alec Phillips writes that the debt limit looks likely to become a constraint for the Treasury in October although November is also likely. According to a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimate released on July 21, the Treasury will exhaust its ability to finance government activities in October or November (Goldman's assessment is that the debt limit will need to be raised by early October).

By way of background, Senate Republican leader McConnell has stated that no Republican would vote for an increase in the debt limit (spoiler alert: they will as they always have in the past although some crisis may be required first). Since Democrats are unlikely to want to take sole responsibility for increasing the limit, Democratic leaders might still insist on passing an increase with bipartisan support, most likely as part of legislation to extend government spending authority after September 30.

Neither the CBO estimate nor McConnell’s statement was particularly surprising, so they are unlikely to affect the outlook for the fiscal package congressional Democrats hope to pass later this year.

With that in mind, here is Goldman's answer to how much of a risk is the looming debt ceiling:

The Debt Limit: How Much of a Risk?

The debt limit suspension that has been in place since 2019 expires at the end of the July. On July 21, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released a projection that the Treasury will exhaust its ability to finance government activities under the debt limit in October or November. To project the timing, one needs to estimate three amounts:

- The cash balance when the debt limit is reinstated: CBO has taken on board Treasury’s projection of a $450bn cash balance as of July 31. This is far more than the Treasury has started with when prior debt limit suspensions have expired over the last several years, as the most recent debt limit suspension bill in 2019 did not prohibit the build-up of cash balances the way that prior suspensions over the last decade had.

- Extraordinary measures: Treasury has various bookkeeping strategies at its disposal to swap debt that counts toward the limit with other debt that does not, and to avoid accumulating debt that it otherwise would. The CBO estimate suggests that these strategies will provide around $350bn in headroom.

- The deficit over the next few months: The Treasury ran a cumulative cash flow deficit of around $170bn in August/September 2019 and $346bn in August/September 2020. During this period in 2021, GS expects a deficit somewhere around $300bn. The deficit in October and November is usually fairly large (an average of around $200bn per month in 2019 and 2020) similar figures are expected this year.

There are two other points of uncertainty regarding debt limit timing:

- The interaction of the cash balance and extraordinary measures: The Treasury projects a cash balance of $450bn on July 31, compared with $134bn when the debt limit was suspended in 2019. That 2019 law states that on August 1 the debt limit will rise by the amount of debt issued since the 2019 suspension to the extent that the debt “was necessary to fund a commitment incurred pursuant to law by the Federal Government that required payment before August 1, 2021.” Since increasing the cash balance does not appear to meet that definition, the new, higher, limit might be set at $316bn below outstanding debt. If so, Treasury would use nearly all extraordinary measures in early August, for a total of $484bn in headroom ($450bn – 316bn + 350bn). By contrast, if the new debt limit is set at total debt outstanding (including the rise in cash) the Treasury will have around $800bn in headroom ($450bn + $350bn). The first interpretation would suggest an early October deadline, while the second interpretation would suggest a late November deadline. CBO’s “October or November” range is wide enough that it is unclear which of these interpretations CBO is following.

- The minimum cash balance the Treasury is willing to run: Ahead of the debt limit deadline in 2017, the Treasury’s cash balance dipped as low as $32bn, but it has not dropped below $100bn in the nearly 4 years since. CBO’s “October or November” estimate refers to the date when extraordinary measures and cash are fully exhausted. As the Treasury is likely to want to maintain some cash on hand, the practical deadline is likely to be several days to a couple weeks before the Treasury fully exhausts its cash and extraordinary measures.

There are two ways congressional Democrats could raise the debt limit:

- A suspension with bipartisan support: Nearly every increase in the debt limit over the last few decades has passed under regular order with bipartisan support. Usually this happens as part of broader fiscal legislation. If the debt limit needs to be raised in early Q4 as most expect, expect congressional Democratic leaders to combine a debt limit suspension with an extension of spending authority, which will need to pass by September 30. While Senate Republican Leader McConnell has indicated that Republicans will not vote for suspending the debt limit, they might ultimately support it if the alternative is voting against spending authority, which would lead to a government shutdown (spoiler alert: republicans always cave after making a big stink first).

- An increase using the reconciliation process: If Republicans block a debt limit suspension under regular order, Democrats also have the option of increasing the limit using the reconciliation process. However, this would have at least three disadvantages: First, while there has not yet been an official ruling on the matter to our knowledge, the Senate’s Byrd rule probably prohibits suspending the debt limit, as has become customary. Instead, Democrats would probably need to increase it by a specific dollar amount (e.g., $3 trillion). Passing a suspension under regular order would avoid a large headline dollar amount. Second, the accumulation of debt over the last two years is likely to become a campaign issue, and Democrats will not want to shoulder the political blame for the increase. While the majority party typically provides most of the support for debt limit increases – some have referred to these votes as a “tax on the majority”—they are likely to want to avoid it if possible. Third, the forthcoming budget reconciliation bill might not pass by the time the debt limit needs to be raised. While it is technically possible to pass a separate reconciliation bill addressing only the debt limit, this looks unlikely in practice.

The timing of the debt limit deadline and the intersection of the issue with the broader fiscal debate is likely to lead to elevated uncertainty in late September when Congress will need to extend spending authority. While Goldman does not rule out a government shutdown if Republicans block an attempt to pair the issues, it is skeptical it will come to this, for three reasons:

- The most disruptive debt limit debates have occurred in divided government. In 2011 and 2013, Republican leaders did not have to block a clean debt limit increase, they simply declined to vote on it. This year, Democratic leaders in the House and Senate will control what legislation comes to a vote and when, which is likely to put greater pressure on Republicans to support a debt limit increase of some sort.

- Republicans have not proposed an alternative. There is no amount of politically realistic spending cut or tax increase that would allow Congress to avoid raising the debt limit. While raising the limit might not be politically popular, spending cuts of the size necessary to eliminate the deficit would be far less popular.

- Filibuster changes looks unlikely, but a debt limit crisis and government shutdown might raise the odds somewhat. Senate rules changes regarding the filibuster appear unlikely this year or next. One reason is that there is always the possibility that some bipartisan compromise might be reached on various issues like police reform or voting rights and, without a high-profile deadline, centrist Democrats prefer to let those discussions continue. While changes to filibuster rules are unlikely to happen under any scenario, a repeat of the fiscal crises of 2011 or 2013 might increase the odds somewhat.

The need to increase the debt limit could also affect the debate over the upcoming fiscal package, even if they are legislatively separate. While it seems unlikely that a showdown over the debt limit would lead centrist Democrats to abandon their support for spending on infrastructure, child care, or extension of tax benefits, for example, it could strengthen their insistence that tax increases or other spending changes offset most of the cost.

As we pointed out recently, the preliminary version of the Democratic budget resolution is reported to be “fully paid for” and suggests downside risk to our assumption that Congress approves $1.5 trillion in tax increases and $3 trillion in new spending (a reconciliation bill of around $2.5 trillion in spending with another $500bn in infrastructure and competitiveness legislation). We expect Senate Democrats to formally introduce their budget resolution next week, which will clarify the targeted amounts of spending and revenue changes as well as whether they intend to pass a debt limit increase via the reconciliation process. While the broad outlines of the fiscal package will be clear before the debt limit debate begins in earnest, the reconciliation bill that includes the actual policy changes is unlikely to pass until after Congress addresses the debt limit.

Disclaimer: Copyright ©2009-2021 ZeroHedge.com/ABC Media, LTD; All Rights Reserved. Zero Hedge is intended for Mature Audiences. Familiarize yourself with our legal and use policies every ...

more

The big problem with debt is that eventually it must be repaid. Of course, in our case those saddled with the mountain of debt are not even born yet. That seems rather unfair, doesn't it?