How I Learned To Love The Debt

The US, Europe, and most of the developed world on are the road to Japanification. Like I wrote last week, we will see financial repression, ever increasing deficits, slower growth, etc. Essentially, the rest of us will begin to look like Japan with its astronomical deficits and ultra-dovish monetary policy.

I tried to emphasize this is not the end of the world. It’s not the best world, either, but we’ve gone too far to come back now. There is no significant constituency for any of the things it would take for the US government to balance its budget. Neither party wants to reduce the deficit, and the MMT fans want to make it even bigger.

That means the rules of investing we have come to know over the last 50 years are likely—as in very, very likely—to change. But we should generally do fine as long as we change our own investment strategies accordingly.

Ben Hunt over at Epsilon Theory recently riffed on Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 masterpiece, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. He did a great parody with it called, Modern Monetary Theory: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the National Debt.

Source: wikimedia

Could we actually see Modern Monetary Theory in the US? Lacy Hunt in his latest quarterly explains how it is theoretically possible for the Treasury Department to issue zero maturity, zero interest bonds to the Fed, which would then deposit dollars into the Treasury bank account. This would, at a minimum, create inflation and possibly hyperinflation. To say it would be destructive is like comparing an ocean breeze to a category five hurricane. It would in fact be a financial disaster of biblical proportions.

I don’t believe it will happen that way, though. We will instead run up debt the old-fashioned way: Japanification and massive amounts of quantitative easing. Let’s look at how that might play out.

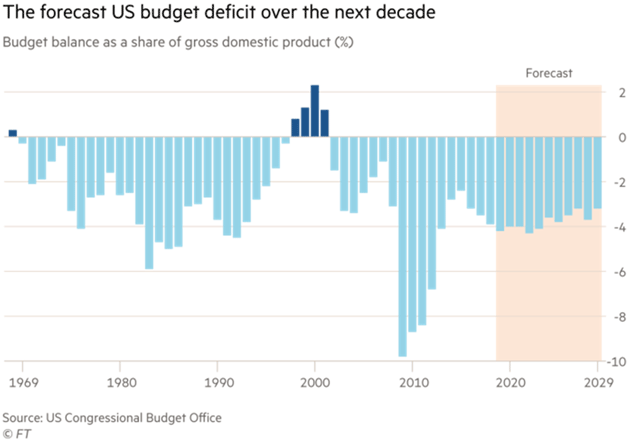

The Financial Times has a very helpful graph using Congressional Budget Office data showing the deficit as a percentage of GDP, both in the past and forecast for the next 10 years. (You can see the underlying CBO report here.)

When you realize that the GDP is well over $20 trillion now, and the CBO projects the GDP to grow, this chart visually understates the reality of growing deficits. Let’s look at another helpful chart, which actually shows the dollar amount of the projected deficits.

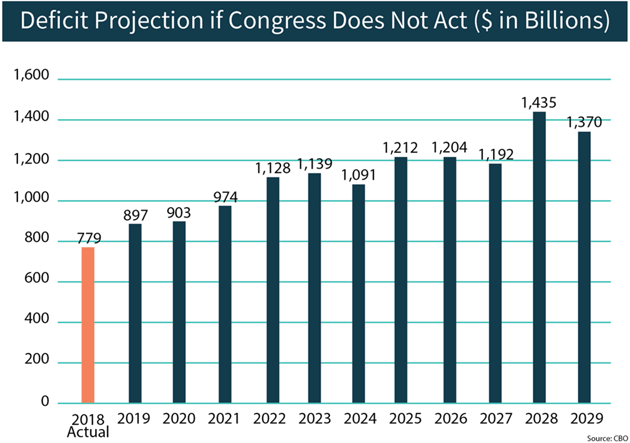

Basically, the projection is an average annual deficit of $1.2 trillion per year for the next 10 years. But there are a few caveats.

First, let’s assume away the real world. To give the CBO their due, they only assume 2.3% GDP growth, very mild unemployment growth, and roughly 2% inflation.

But here’s the kicker. Well, actually there’s two. They assume no recession and they make no allowance for the roughly $400 billion per year in off-budget expenditures that I described last week.

The off-budget expenditures mean that, even without a recession, the debt will rise $1.6 trillion per year for the next decade. That means the national debt will be $40 trillion by 2029.

If, as I expect, there is a recession, we will reach that $40 trillion number sooner, sometime in 2026 through 2028. The deficit in a recession will be a minimum of $2 trillion per year and maybe much higher than those suggested above.

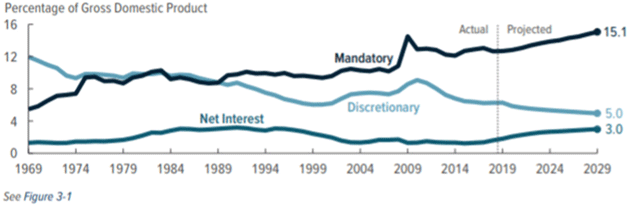

There will be some token movement to reduce spending, but it won’t make much difference because “mandatory” spending (a euphemism for Medicare, Social Security, and other entitlement programs plus interest on the debt) plus defense spending overwhelms so-called “discretionary” spending. Here’s the CBO chart (again in terms of GDP because the absolute numbers would scare you).

Source: CBO

Even if we could cut some discretionary spending, the deficits would still be huge as there is no constituency for cutting entitlement programs. We will talk about why growth will actually slow under such a scenario in a later letter. Today’s question is, where will we get the money to pay for this spending?

Answer: The Treasury Department will sell bonds and run up the debt. That’s a given. Then there will be a recession, as there always is, and then the Federal Reserve will take interest rates down to the zero boundary (otherwise known as financial repression and the devastation of savers), followed by unprecedented amounts of quantitative easing… just like Japan has done.

Again, this isn’t the end of the world, at least if we pursue it that way. Full-on MMT would be much, much worse, and if I seriously expected it, I would be preparing to ride out a hyperinflation scenario. But I do not think that will happen.

Is it possible? Sure. The most dangerous thing for investors is to not imagine what could go wrong with their basic thesis (hat tip Ben Hunt).

Right now, my base case is for a more or less deflationary world.

Monetary Hockey Stick

Now let’s think how we got here. The response to the last crisis setup the next one. A lot happened in 2007–2009, during which we endured a recession that left little chance for reflection. Now we have that chance.

Those in authority back then faced enormous pressure to “do something.” Letting nature take its course may well have been the best strategy, but it couldn’t happen that way in our political system. They had to act.

(Sidebar historical note: there was a Crash/Depression in 1920–1921. You never read about it. President Warren Harding simply did nothing and let prices and markets clear. It was all over by mid-1921, and we got the Roaring 20s. No Fed or government intervention, except the Fed did raise interest rates to 7% after inflation World War I, so they get a share of the blame. And there was the gold standard, so no QE was available. Back to our world…)

In 2008–2009, we got things like TARP—the Troubled Asset Relief Program that used $431 billion of your money to buy loans that banks no longer wanted on their books. The government eventually sold most of them, as well as equity warrants received from participating banks, so the net cost came out much lower. But that wasn’t a sure thing.

What we now forget is that TARP helped banks that weren’t even banks before that point. Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and numerous other broker-dealers and insurers hurriedly got bank charters specifically so they could be part of TARP. The government welcomed it, too. That’s the kind of unpredictable change I described last week.

But these fiscal and regulatory surprises pale in comparison to the Federal Reserve’s unprecedented monetary actions.

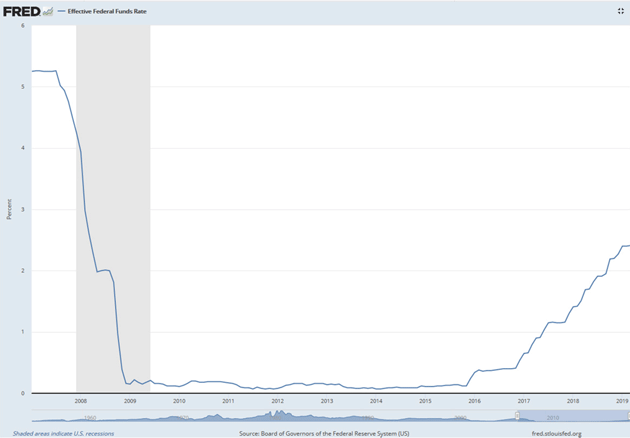

Rate cuts were only part of it and not the most important, but they were huge. In August 2007, they cut Fed Funds a quarter-point from 5.25% where it had stayed for some time. A year later, it was down to 2%, and soon was effectively zero. Compare that to the current cycle, which spent four years raising the rate from that effectively zero level to the present 2.5%.

The Fed is perfectly capable of moving rates far more aggressively than we have seen recently, and in either direction. But the bigger and even more aggressive policy move was in asset purchases, which included but weren’t limited to quantitative easing.

When the crisis hit, the Fed by law could only buy certain kinds of assets: Treasury securities, bank debt, federally-backed mortgage securities, and the like. They didn’t change the rules but instead stretched them far beyond what anyone envisioned could ever happen.

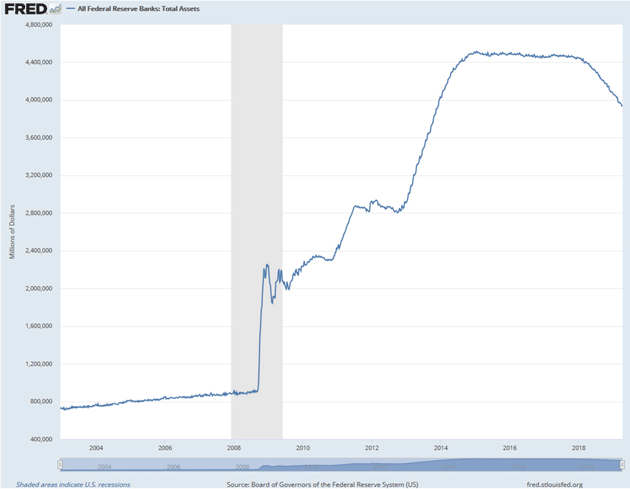

That hockey-stick jump in the Fed’s balance sheet assets wasn’t on anyone’s radar, but it happened. The Fed then added several more rounds before finally topping out and recently beginning to exit.

Was any of this the end of the world? No. The markets absorbed it all and even performed well. In fact, markets performed well because they absorbed all this craziness. In that lies the seed of our next cycle.

Killer Debt

Recently I sent Over My Shoulder members a Swiss newspaper interview with my friend William White. Bill is former chief economist with the Bank for International Settlements and my favorite central banker. He speaks with unusual candor.

In discussing the current move to loosen policy, the reporter asked, “How did we end up in the debt trap?” Bill’s answer:

We were encouraged to do this. Just think what we have been doing since 2007. Monetary easing is an invitation to take on more private sector debt. And fiscal expansion is by definition an increase of government debt. Both instruments carry the risk of higher debt levels that eventually will kill you.

In the Great Recession, we had both fiscal easing (TARP, expanded safety net programs, etc) and monetary easing (lower rates, asset purchases, QE). The result, exactly as Bill said, was sharply more government debt and private sector debt.

That may seem counterintuitive, since recessions supposedly bring deleveraging. That happened, but not uniformly. Some deleveraged while others added more, and the latter group was much larger. And the Fed’s vast liquidity injections enabled it.

Bill went on to explain that debt problems are about solvency, but central banks provide liquidity. A fractional reserve banking system has a lender of last resort in order to avoid collapse in a bank run. Bailing out borrowers who can’t repay is not its mission or its talent.

Nonetheless, under pressure to act, the Fed and its peers did what they could: throw money in all directions, hoping some of it would stick. Some of it did, too. The new liquidity found its way into assets whose prices then rose, enabling more borrowing, driving asset prices higher again, and here we are.

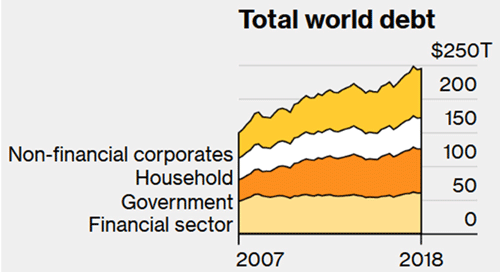

According to the Institute for International Finance, global debt was $244 trillion as of Q3 2018. More than half of it was financial and non-financial corporate debt. About 27% ($65 trillion) was government debt (not counting unfunded liabilities, which are huge).

Source: Bloomberg

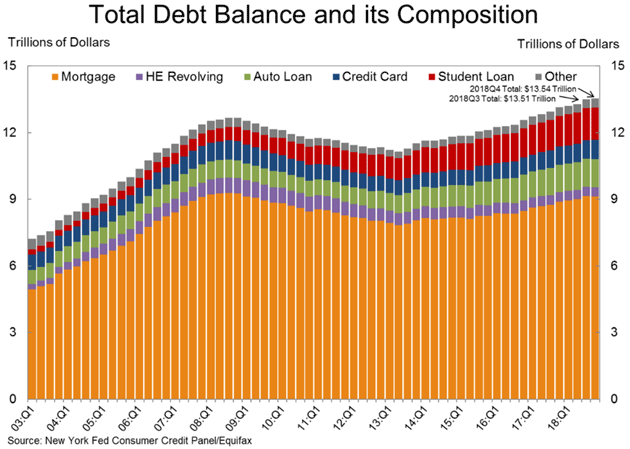

Household debt was the small category and hasn’t grown that much in the US. Here’s a closer look via the New York Fed’s quarterly survey.

You can see in the chart how US households retrenched in the recession, then began slowly adding more debt in 2013 and after. Mortgage debt is still slightly below its pre-crisis peak.

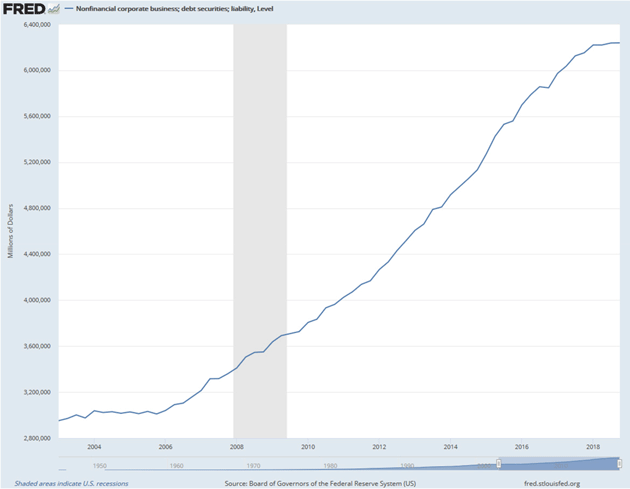

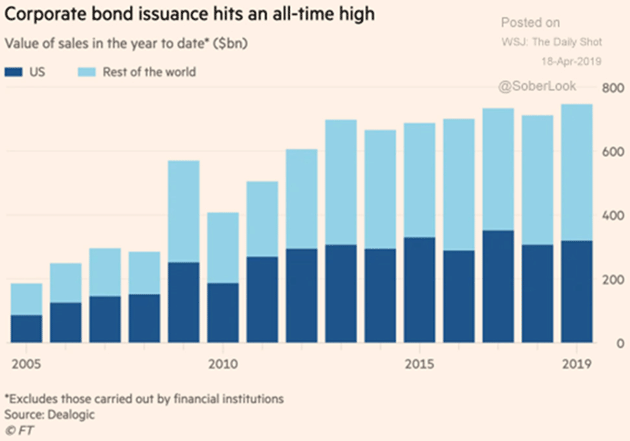

Corporations did not limit themselves like families did. Here’s nonfinancial corporate debt growth for that same period (2003–2018).

The recession (shaded area) had almost no effect on corporate debt growth, which continued merrily higher. Note that this is only securitized debt; much more exists on private books. You could argue that the added debt is not so dramatic as a percentage of GDP, which also grew in this period. That’s true, but it’s also riskier debt. The proportion of bonds at junk or near-junk status has grown significantly.

I’ve quoted several times now my friend Peter Boockvar’s statement, “We no longer have business cycles, we have credit cycles.” His point: Falling asset prices won’t be a result of the next recession; they will cause the next recession. And asset prices will fall when the free-flowing credit that pushed them so high recedes, which it is doing right now thanks to the Fed’s two-factor experiment of simultaneously hiking interest rates and reversing QE.

The Fed is now at least pausing that experiment and appears set to reverse it later this year. I fear they are acting too late. The latest corporate earnings news and lots of other data suggests the cyclical weakening has begun. The next marker will be some high-profile debt defaults, probably among lower-rated issuers. I don’t know who: WeWork, Tesla (TSLA), name your favorite. But somebody is going to run out of cash and find themselves unable to refinance for the 97th time. And then the real fun will begin.

Dominos dropping

Years ago, I started calling Japan a “bug in search of a windshield.” I was certain their economy would go splat as they ran huge government deficits, cratered their own currency, and had the Bank of Japan buy every financial asset that wasn’t nailed down.

Well, the Japanese have enthusiastically implemented all those policies. I’m not going to say it worked… but the bug hasn’t yet hit the windshield. Other governments and central banks have noticed, too.

Here’s what they observe. Japan has spent decades with zero or negative rates, engaged in massive QE and boondoggle spending, gone in and out of recession, and somehow stayed on its feet. An economic boom it is not, but the country avoided the worst nightmares. That’s a “win” in the way central bankers think.

Meanwhile, Mario Draghi’s European Central Bank tried a similar strategy to the extent it could, given that the Eurozone lacks a unified fiscal authority. It seemed to be working, well enough that the ECB decided last year to end some of the extraordinary measures. But simply talking about it appears to have put the Eurozone economy into a mild flu. So now they are back on a Japan-like course.

Italy alone has so much debt it could easily become another Greece, but far larger and more difficult for the rest of Europe to rescue. Italy is already in recession, albeit a mild one (so far), but its debt load is still rising. At some point, it becomes a systemic risk to the Eurozone and EU.

And the US? As I’ve said, the Fed waited too long to start exiting from crisis-era measures. They gave the economy time to go from “dependence” on easy money to outright “addiction.” And as we all know, addictions are very, very hard to break. So now the Fed has cold feet, too. Further tightening appears unlikely. They will try to cut rates as the weakness grows more obvious, but it won’t help, and they will start digging through the toolbox for something else to try.

Whatever they do will probably surprise and alarm us. It will not have the desired effects, at least not as fast as they want. But it also won’t kill us if we prepare for it.

The dominoes are starting to drop as expected. To review…

- The entire world is up to its ears in debt, thanks to a decade of central bank action.

- We are late in a growth cycle that is going to end, possibly soon.

- Whenever it does, US government borrowing needs will skyrocket higher from already astronomical levels.

- The Federal Reserve will end up monetizing this new debt.

Working off that debt will take years, possibly decades. Hence the long, slow Japanization I’ve described. I don’t think we will endure it for 30 years like Japan has. We will instead force a worldwide default, which I’ve dubbed the Great Reset.

Beyond that lie better times. But we’ll go through hell first.

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe now and receive the full version of John Mauldin's Thoughts from the Frontline delivered to your inbox each week.

Towards the middle ...

more

Another great article. But unfortunately, our central bank did not, and does not care about small business. Why was it ok for the BOE to bail out small business in the UK while the Fed allegedly couldn't? The Fed is destroying the biggest job creator. It makes the wealth divide much more serious. And the tax cuts were skewed to the wrong people, making it necessary to cut more to the very people the Federal Reserve hurts with its policy. Now MMT is the backlash. You capitalist leaders have really screwed up.

It's a good question.