Higher For Longer - Implications

Are we there yet? No, but we’ll get there. When? Eventually. Really? Except, um, we might miss the exit. Oh, no! But don’t worry, we’ll know when we’ve gone too far. Okay! Well, kind of. Help! What are you up to? That’s easy: we’ll be higher for longer. And what does it mean? What you see is what you get. Let me explain:

Why it matters: The Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) controls the bazooka; that is, they control the “risk-free” rate, that is, amongst others, they set the interest banks (and some non-banks, such as the money market funds) earn on overnight deposits at the Fed. Through that, they influence investors’ appetite to fund risky ventures, ranging from providing consumer loans to helping finance risky endeavors, notably also the valuation of stocks, also known as “risk assets”.

The big picture: To fight inflation, the Fed is committed to “higher for longer”. We may agree or disagree with the Fed’s approach, but we may be well served to take the Fed literally. Specifically:

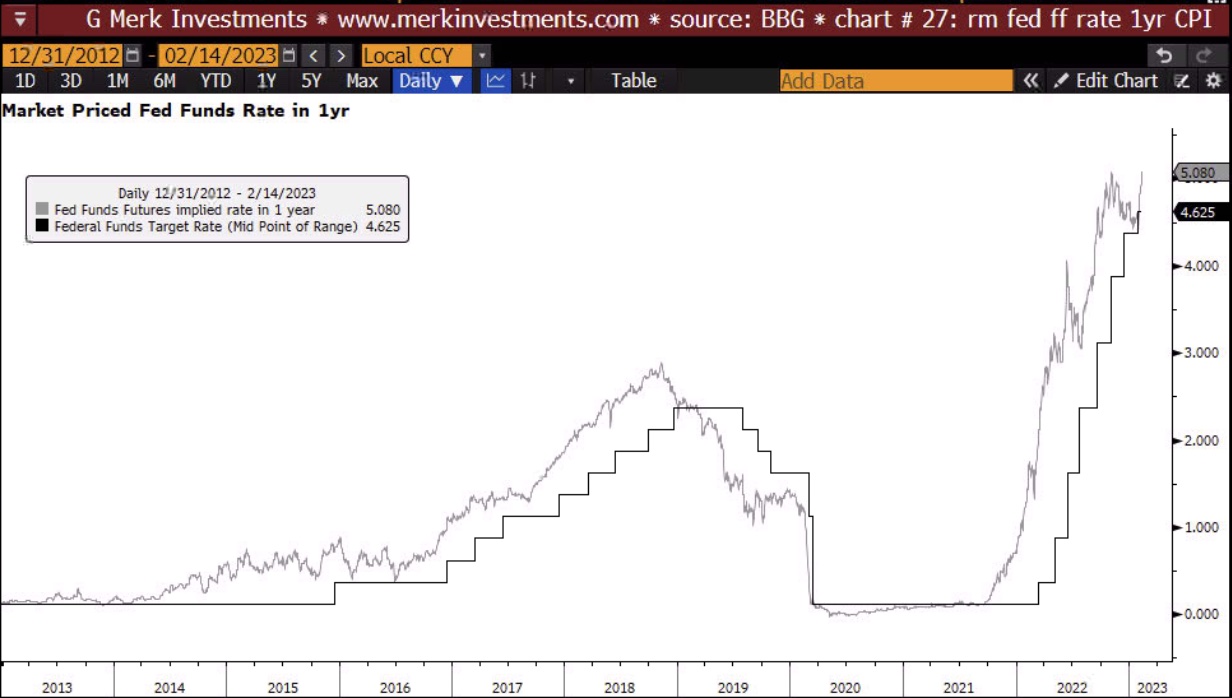

- The Fed had only initiated rate hikes in March 2022, raising the Federal Funds rate by 0.25. At the March 2022 meeting, the February Consumer Price Index (CPI) was available indicating 7.9% year-over-year inflation. The Fed’s sense of urgency increased only thereafter, raising 0.5% in May, then 0.75% in June; that month the month CPI accelerated to 9.1%. In the chart below, the Fed’s Fund target rate is depicted black; in grey is what the market priced in for the rate to be a year down the road; and in blue is the CPI at the time:

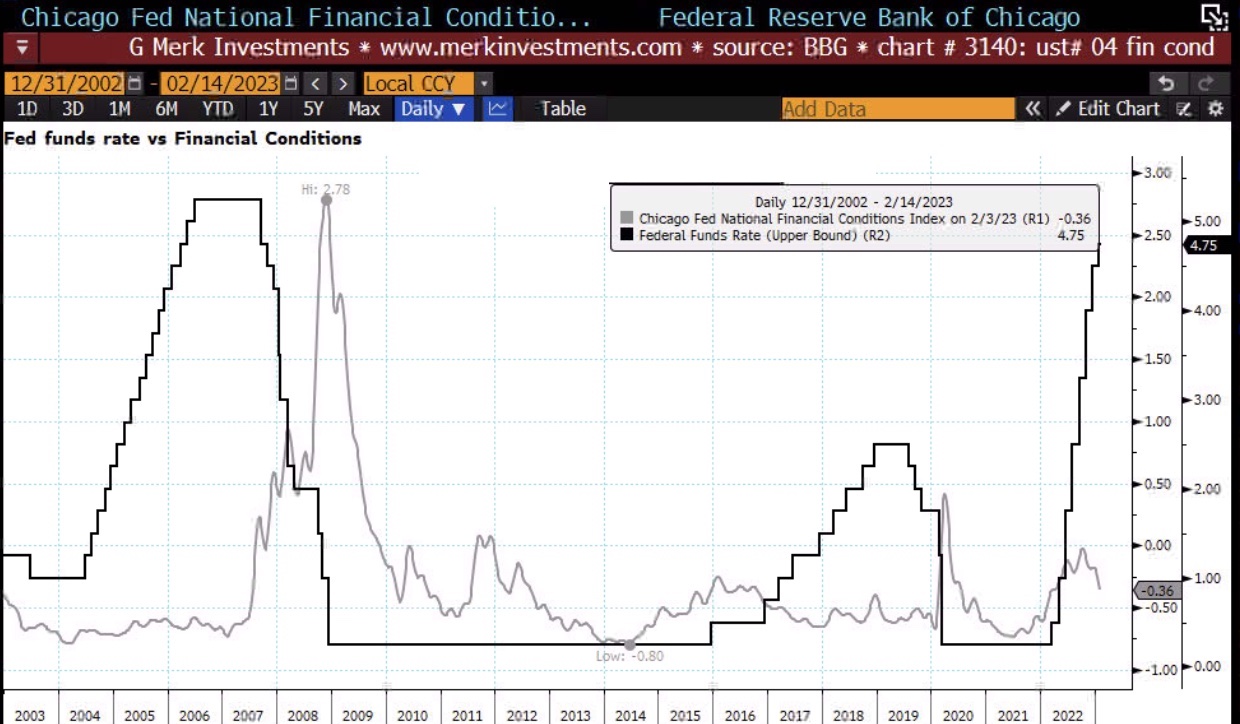

- I’ve argued that the “whole point” of raising rates is to “tighten financial conditions.” In plain English, this means it is more difficult to access credit; there are many (imperfect) ways of measuring financial conditions. Below is what I believe is one of the better indices, the Chicago Fed Financial Conditions Index. Powell has expressed frustration that despite higher rates, financial conditions haven’t tightened further.

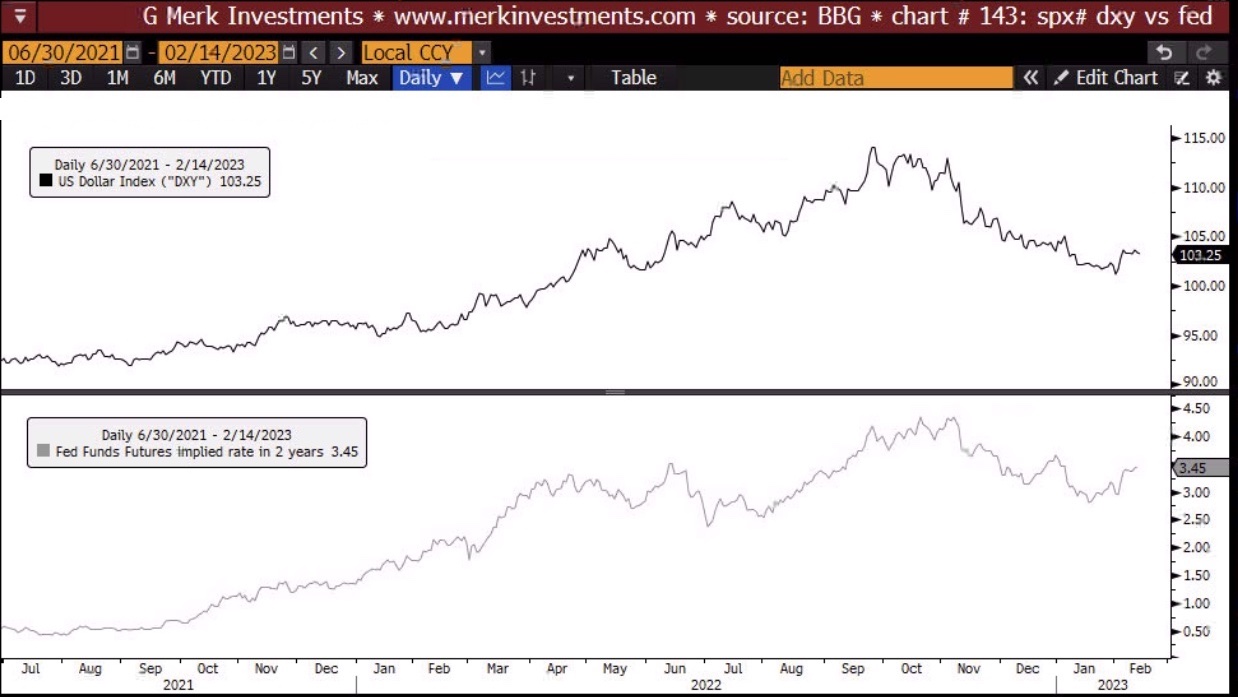

- In my assessment, the Fed’s sense of urgency started to abate in the early fall of 2022, with explicit signals for a lower pace of rate hikes after the November Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) Meeting. Markets are of course forward looking. Below is what the market is pricing in the Fed Funds rate to be 2 years out (lower pane). I’ve called the Fed’s reduced urgency and subsequent step down to a lower pace of rate hikes a pivot. If you look at the upper pane of the image below, you see why. The dollar index, reflecting the US dollar’s value versus a basked of currencies, has seen its recent peak – and I would argue a secular peak – last fall:

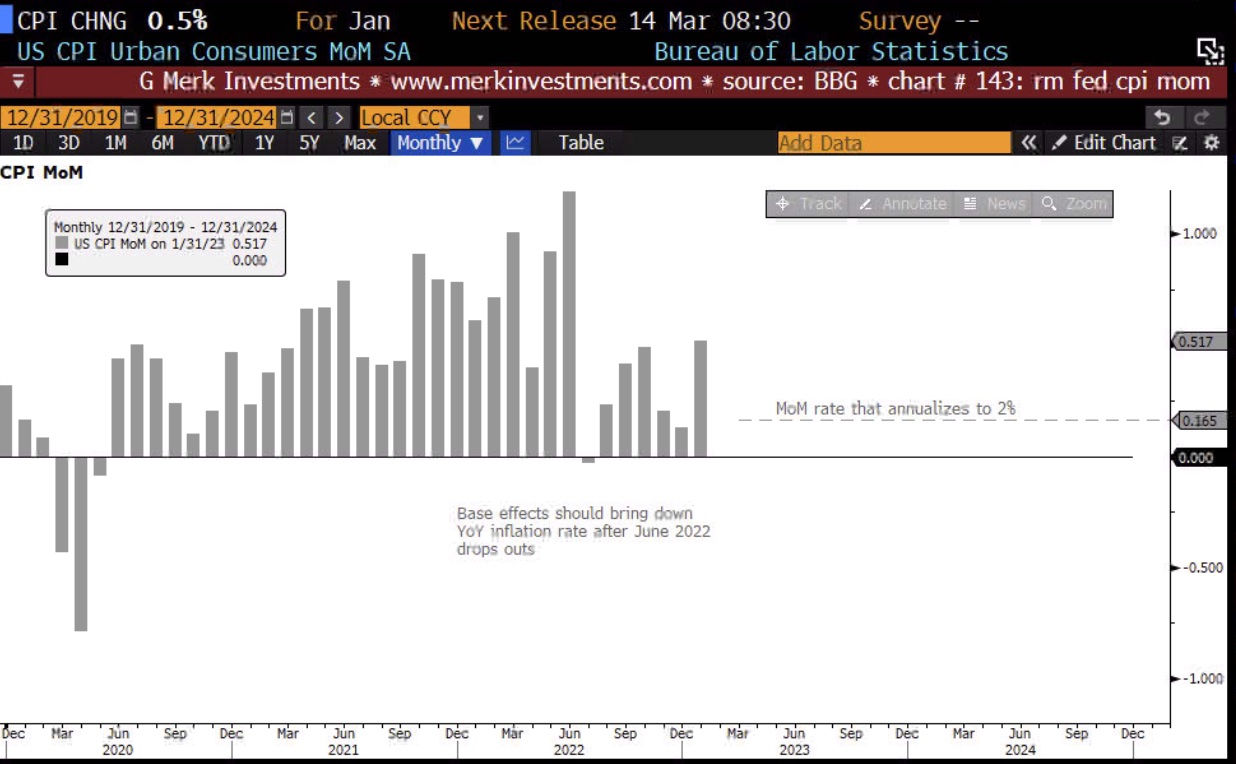

- What the Fed wants to see is that interest rates are above the inflation rate. That sounds easy enough (why they didn’t raise rates faster, earlier?). When you talk inflation, there are lots of measures and any year-over-year measure contains data that references a data point that is, well, a year old. We will have to wait until after June for the high reading from last summer to drop out to provide the likelihood of a more benign inflation reading.

- As such, the Fed is keenly watching month-over-month measures, annualized. While the public is glued to the CPI, the Fed’s official target is “core Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) inflation.” Relevant to our discussion is that the Fed might have been willing to pause if those readings for the first quarter come in what they deem at acceptable levels. Except that the February PCE inflation report won’t be available in time for the Fed’s March FOMC Meeting. This, in turn, means the Fed can’t really pause before the following meeting which is in early May. And if you see a calendar dependency here, um, just note that the Fed claims not to be calendar dependent. Go figure.

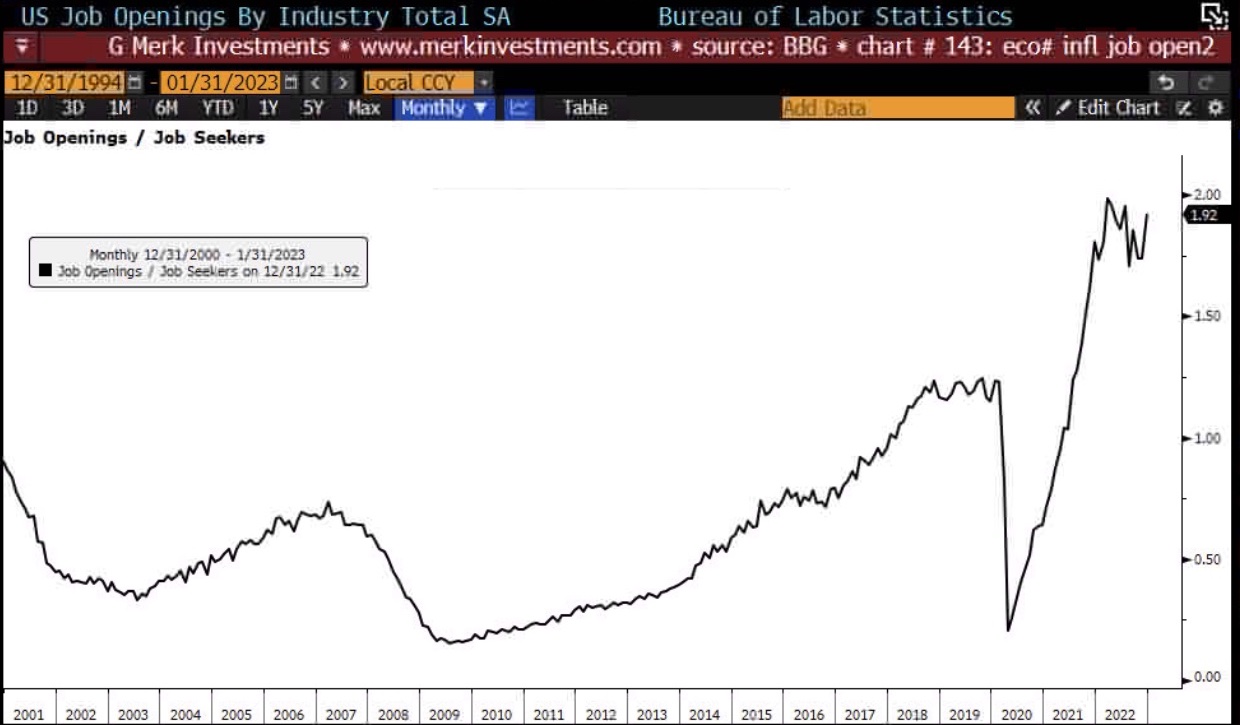

- Except the January jobs report was much stronger than expected. That’s a problem because the Fed wants the economy to slow down. There continue to be almost two job openings per job seeker. While some argue this is not necessarily inflationary, the dogma at the Fed (and common sense) dictate caution. Upon the release of the jobs report, the market priced in another 0.25% rate hike in May with the possibility of another June rate hike hovering around 50%.

What it means: In my assessment, the only conclusion to draw from this is that the Fed will be, um, data dependent.

Regarding economic or jobs growth, it means:

- If economic data come in weaker than expected in the coming weeks, the Fed may well pause in May.

- If the economic data come in stronger than expected, the Fed may continue to hike for a while at 0.25% increments, with the caveat the voting members at the FOMC are more “dovish” than last year, meaning there will be increasing pushback against further rate hikes if they are to persist.

Regarding inflation data:

- In recent months, inflation data have not had significant outliers. While that may be comforting to the Fed, in his recent book entitled “21st Century Monetary Policy”, former Fed Chair Bernanke cautions that once inflation is high, it no longer behaves linearly. I agree that this is a significant risk, meaning it is likely that one of the upcoming inflation readings will be much higher than expected. IMHO this poses the biggest risk to a market that is pricing in a comparatively benign inflation outlook.

The Fed will be late:

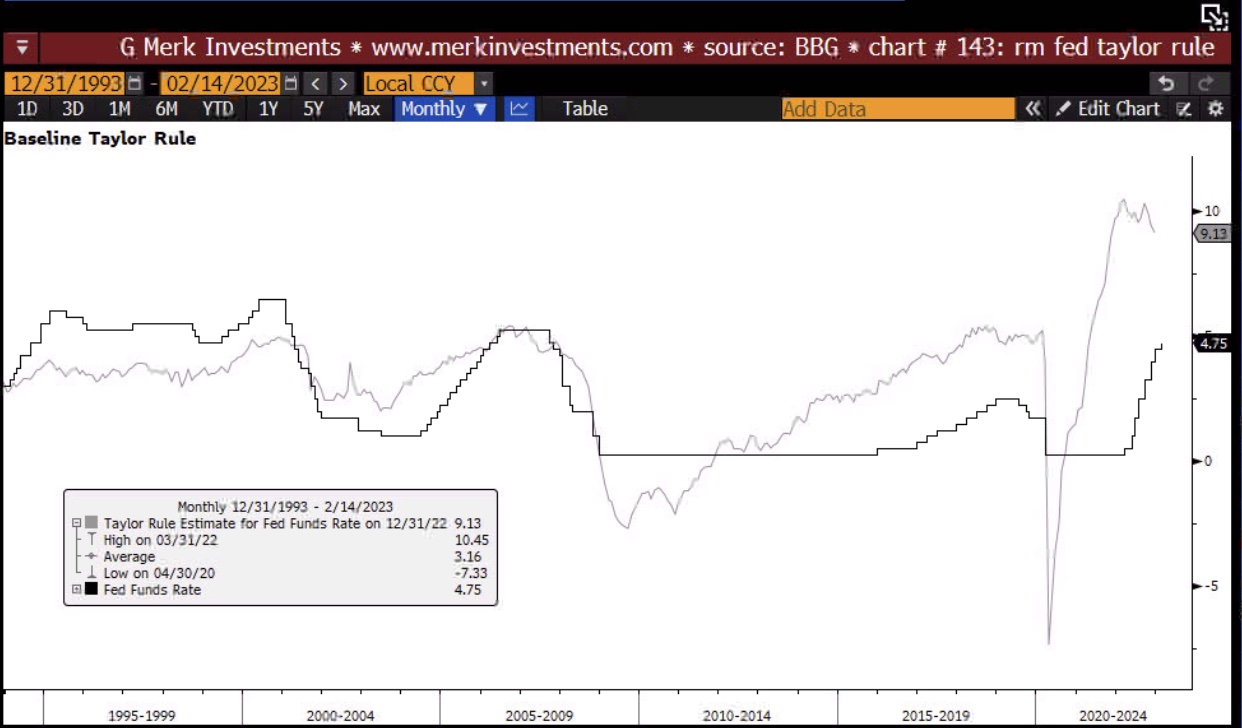

- Milton Friedman first said that lags in monetary policy are “long and variable.” The difference today is that central bankers appear to use this phrase to indicate they are done hiking rates. Bank of Canada’s Governor Tiff Macklem recently used those magic words to indicate a pause in the rate hiking cycle. It is of course it is correct that the real economy takes a while to reflect a new rate environment. In this context, the Taylor Rule suggests the Fed should be cutting rates right now, albeit from much higher levels (the Taylor Rule is a rules-based approach to monetary policy developed by Stanford Professor John Taylor in 1993):

- To me, this delay increases the odds of a recession, if not a severe recession.

Implications for markets: I don’t have a crystal ball, and I can’t give specific investment advice. What I can do is suggest investors may want to take what I believe are apparent risks into account in their portfolio allocation:

- The risk of higher-than-expected future inflation reading throwing a major curveball into markets at some point in the coming months is more than a remote possibility; in my view, it is a high likelihood.

- In our analysis, equities perform okay in shallow recessions. In more severe recessions, equities can suffer substantially. That said, to the extent inflation remains elevated, if the stagflationary period of the 1970s is any guide, equities can perform poorly on an inflation-adjusted basis.

- In our analysis, gold and gold miners have historically been early beneficiaries in an economic downturn, reacting early once the market perceives monetary policy to pivot. It’s no accident I use the term pivot to the Fed’s reduced pace of rate hikes last fall; as shown earlier, the dollar may have peaked at the time as well.

- At any time, there is of course the risk of a “shock” – the “unknown unknown” – the further one looks into the future, the greater the likelihood of such a shock occurring. While such shocks (no jokes about alien invasion, please) are not known, this is part of the reason why markets tend to price in some easing into future rates. If that were to unfold, the dollar might get a short-term rally and the Fed’s hands might be forced to cut rates sharply.

- The Fed argues that markets absorb information faster these days and, thus, there is little risk in their “higher for longer” strategy. Notably, they argue, they can always cut rates. With due respect, this time is not different. The reason why the market absorbs information “faster” is because the Fed is providing more explicit forward guidance. When, in the spring of 2022, the Fed specified its “higher for longer” strategy, the market priced it in. Financial conditions that aren’t all that tight are a direct consequence of that as the upcoming recession has been called the most predicted recession ever. That is, consumers, firms, and markets have had ample opportunity to prepare for it. And that may well be the reason why the recession will be shallower than it would have otherwise been. The Fed may well need to raise rates further as it otherwise would have had to, to create sufficiently tight financial conditions.

- What is different is that the Fed all but promises to be “higher for longer”, meaning that when weaker economic data come in, the Fed may be reluctant to ease. That’s in part because the Fed is aware that inflation could show its ugly head any time again after the episode we have gone through. Again, an argument for a deeper recession.

What about the market pricing rate cuts later this year?

- As indicated earlier, some easing down the road is always priced into it to reflect the risk of a shock. However, the sort of easing that’s priced in is more significant than would be if the market took the Fed seriously with its call that it will hold the line unless there is some shock that warrants urgent action. What gives?

- In my view, the Fed’s main problem is that “higher for longer” is not a strategy, but a tactic. The goal post is moved with any data point that comes out. Fair enough. Except, the quirks of the calendar as elaborated on above aside, we can’t really see beyond the next goalpost. What that means in practice is that the market is likely to continue to predict rate cuts within months, even if rates move higher. This regime will shift once the Fed signals a pause in earnest (listen for more pronounced statements that Fed policy acts with a lag). At that time, it depends on how weak economic data are, but odds are that the market will continue to expect rate cuts sooner than the Fed is comfortable with. To fix this, the Fed would need a completely different framework, something Fed Chair Powell IMHO is not capable of communicating, but that’s another Merk Insight for another day.

Implications for stagflation:

- As many of our readers know, we have cautioned about the risk of stagflation. Stagflation can be thought of as a supply shock followed by policy mistakes. That is, when supply lines are cut, the politically attractive reaction is often an economically foolish one. For example, you can’t increase oil production by handing stimulus checks to consumers. There is a reason why the stagflationary environment in the 1970s lasted over a decade. We may have more data today, but human nature has not changed.

Implications for correlation:

- Unlike last year, when many investors were frustrated that their way of diversifying their portfolios didn’t work, I would not be surprised if 2023 is the year when diversification will come back into fashion. With that, I don’t mean we will revert to an era where the S&P 500 outperformed just about any other investment for years in a row, but an environment where true diversification that includes other asset classes, international equities, small-cap value, also bonds, can play important roles in a diversified portfolio.

- Indeed, what I may refer to as “peak hawkishness” at a Fed that has reduced the pace of rate hikes might signal that longer-term real interest rates may be near their peak which could benefit TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities), gold, and gold miners.

More By This Author:

Equity Market Chart Book

Business Cycle Chart Book

Equity Market Chart Book - Thursday, Dec. 22